Immigrants To Canada Can Find Work, But Moving Up The Ladder Is Another Story

MONTREAL ― Rola Dagher’s journey from childhood in a small Lebanese town to president of Cisco Canada reads like something out of an improbable Horatio Alger novel.

Dagher came to Canada at age 17, escaping Lebanon’s civil war with her baby daughter, Stephanie, in the trunk of a car.

In Canada, she worked her way up from retail sales clerk to telemarketer to high-performing sales exec at Dell before tech giant Cisco contacted her to head up its Canadian division.

“When they called me for the president’s role, I thought they called the wrong person,” Dagher said in a phone interview. “They were like, ‘No no, we’ve followed your career.’ It was an awesome and overwhelming moment for me.”

Add to that Dagher’s lack of formal education ― she describes herself as having a “master’s degree in life” ― and her battle against cancer a decade ago, and you have the makings of a truly unique story of overcoming challenges.

But that’s the problem. Dagher’s story is unique, and her success required beating overwhelming odds stacked against immigrants ― particularly female and racialized immigrants ― at the top echelons of Canadian business, government and non-profits.

According to a recent report from the Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council (TRIEC), despite the city’s reputation as the world’s most multicultural place, immigrants face a solid glass ceiling when it comes to breaking through to the top positions in their field.

Overall the situation for job-seeking immigrants looks good ― the unemployment rate among this group near a record low, as is the case for the country as a whole ― but moving up the ladder once you’re in the door is another story.

Despite accounting for nearly 50 per cent of Toronto’s population, immigrants account for just six per cent of leadership roles in the private, public and non-profit sectors, the study found.

Watch: Toronto immigrants make less today than in 1980. Story continues below.

“Career stagnation exists even in fields most commonly employing newcomers,” TRIEC said in a statement. “Immigrants are not climbing up the ladder in financial and insurance as well as professional, scientific and technical services, where the largest concentration of immigrant professionals work.”

The situation looks even worse for women and people of colour; only one per cent of Toronto’s corporate executives are racialized immigrant women, despite being 8 per cent of the broader population.

Margaret Eaton, TRIEC’s executive director, says unconscious bias is a key barrier.

“People ― especially in higher positions ― tend to hire people who look like themselves,” she told HuffPost Canada.

“You want to hire someone who’s a McGill grad. You want to hire someone you can talk to about sports teams. … We feel like there’s risk in hiring or promoting that person who’s unknown.”

Risk aversion

If Canada is doing worse on boardroom diversity than some other countries, that may be because “Canadian businesses are particularly risk averse,” Eaton said. In the U.S. and U.K, she added, they “care more about talent.”

But it’s not just conscious or unconscious bias: In some ways, keeping immigrants out is a matter of policy in Canada. As many migrants can attest, Canada often fails to recognize foreign credentials, particularly in regulated professions such as medicine, accounting and engineering.

This is among the reasons that immigrants are far less likely to be working in the field they were trained. According to a Statistics Canada analysis of 2006 census data, only 24 per cent of foreign-educated newcomers with a university degree were working in their field of specialization at that time, compared to 62 per cent among their Canadian-born counterparts.

“The regulated professions in particular are very keen on protecting their market,” Eaton said. “They don’t want to have a lot of other people coming into the marketplace.”

She noted that some provinces, including Ontario and Quebec, have appointed fairness commissioners to ensure that regulated professions have transparent and fair practices for licensing. She says this has been “somewhat” but “not entirely” effective in addressing the problem.

“We are seeing more immigrants entering those professions,” she said.

The problem extends beyond regulated professions, too. For example, Dagher would not have landed the top job at Cisco Canada if the company had insisted on a formal education for her position.

But how does an employer assess whether an immigrant does indeed have the skills needed to do the job? That’s “tricky,” Eaton admits, but she urges hiring managers to turn to competency assessments: Processes designed to help uncover and assess people’s abilities.

And it “behooves employers to look at themselves,” Eaton added. “Look at the data. Do you see what we see? Then think about how you’ll create targeted pathways (for people from marginalized groups) to the top.”

Better business

For Dagher, increasing diversity at the top of the corporate ladder isn’t just about seeing more people like herself at work ― it’s a key ingredient to business success. Companies that lack diversity of thought and ideas will miss out on opportunities that other, more diverse companies will be able to capture, she says. Dagher stresses that seeking out diverse candidates shouldn’t be about “checking a box” for executives.

“Diversity in thought … is just the smart thing for businesses. I don’t want people who think like me and do the same things I do.”

She adds that she would never simply hire a woman for being a woman, for example, but “I encourage my team to find more female leaders.”

So if you’re an immigrant facing a glass ceiling in your career, what should you do? Both Dagher and Eaton mention the importance of finding a mentor ― someone who can help you navigate the politics of the office and the cultural differences between Canada and back home.

“Find organizations that can help you, and find where your passion is,” Dagher said. “Where do you want to be, what are your goals and how can you get there?”

But that isn’t a guarantee of success.

“You won’t be necessarily recognized just for doing a great job,” Eaton said. “People assume if they do a great job they will move up the ranks. Our research shows that isn’t necessarily the case.…

“Unfortunately a piece of this advice is you’re going to have to be better than those around you,” she said, adding that “this has been true for women for decades.”

Immigrants should “believe in themselves, in their capabilities and (not) let anyone out there crush their dreams, because we need them as much as they need us,” Dagher said.

She suggests patience and persistence will be needed too.

“I’ve been in Canada for 30 years and it took me 30 years to get to where I am today. … It’s a journey.”

You May Also Like

Sprunki: A Comprehensive Exploration of Its Origins and Impact

March 19, 2025

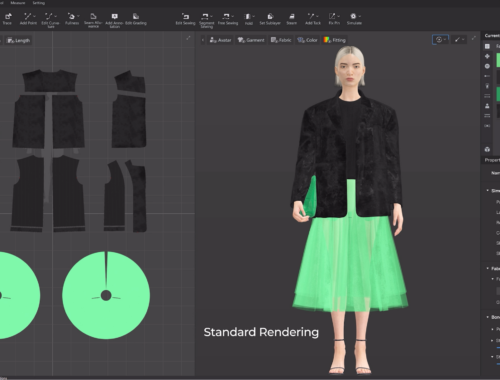

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025