How Wilma Rudolph Became the World’s Fastest Woman

Badass Women Chronicles

How Wilma Rudolph Became the World’s Fastest Woman

Wilma Rudolph won three Olympic golds and was among the first athletes to use her celebrity to fight for civil rights

Jun 8, 2018

Jun 8, 2018

Wilma Rudolph won three Olympic golds and was among the first athletes to use her celebrity to fight for civil rights

For Olympic runner Wilma Rudolph, the proverbial starting line was way behind most Americans. She was born premature and sickly to a poor black family in the Jim Crow South in 1940. As the 20th of 22 children, she was well loved but struggled with illness for much of her childhood, battling double pneumonia, scarlet fever, and whooping cough. A bout of polio left one leg crooked and her foot curved; the neighborhood kids in Clarkesville, Tennessee, teased her mercilessly. Forced to wear a leg brace, she often sat at home feeling rejected and alone. “There really wasn’t much to do but dream,” she wrote in her 1977 autobiography.

Over the years, Rudolph managed, against all expectations, to improve. There were few medical facilities available to African Americans in her town, so every week, between the ages of six and ten, she boarded a segregated bus and traveled 50 miles to a hospital where she could receive treatment. At home her mother painstakingly administered her own remedies. One day when she was nine years old, to the shock of her family and the community, Rudolph took off her brace and walked without it. It would take a few more years for her to move normally, but she was hell-bent on being a healthy kid.

Rudolph loved sports, and in the summer after sixth grade, she was able to join in on basketball games, shooting hoops with whoever was at the playground, which usually meant a bunch of boys. In high school, she started running track. She liked it so much that she skipped classes and snuck into a nearby college stadium to practice, sometimes loitering near the coach to pick up pointers.

“Running, at the time, was nothing but pure enjoyment for me,” she later wrote. “I loved the feeling of freedom… the fresh air, the feeling that the only person I’m really competing against in this is me. The other girls may not have been taking it as seriously as I was, but I was winning and they weren’t.”

When she was a sophomore in high school, renowned Tennessee State University women’s track coach Ed Temple scouted Rudolph at a basketball game and invited her to a summer training camp. Before that she’d been running on pure love and natural ability, cleaning up at regional competitions. At the camp, she conditioned herself to run at an elite level—Tennessee State, a historically black university, was a powerhouse of women’s track—and learned technique, like how to run smooth and loose. At age 16, she had never heard of the Olympics, but Coach Temple thought she was talented enough to run in the Olympic Trials. Weeks later she made the team, the youngest person in the American field.

Because they knew that her family was scraping by, Clarkesville locals banded together to buy Rudolph luggage and some clothing so that she could travel to the 1956 Melbourne Games in style. In the 200-meter event, she did well enough to advance to the semifinals but missed the cut for the finals, a crushing defeat. Her disappointment fired her up for her other event, the 4×100-meter relay, and she, Mae Faggs, Margaret Matthews, and Isabelle Daniels earned the bronze medal. Rudolph was thrilled. She vowed to return and do even better.

In the following years, Wilma Rudolph continued to break records and dominate women’s sprints on the international stage. She was known at one point as the world’s fastest woman and was among the most successful and famous athletes of her era. At six feet tall she was graceful and lithe; she was also thoughtful and humble, and quickly won over the press, which often touted her as a symbol of the merits of democracy and American perseverance during the Cold War. While her underdog story of athletic victory has been celebrated in the media and popular culture, through countless articles and even a made-for-TV movie, her lifelong struggle against racism and sexism, and her powerful role as a champion for civil rights and gender parity, are less well known.

“She was one of the first African American athletes to use her celebrity to fight against injustice,” says Rita Liberti, a sports historian and professor of kinesiology at California State University, East Bay, and a coauthor of (Re)Presenting Wilma Rudolph. “Without question, Wilma Rudolph wasn’t the only one, but she was among a handful of African American women who really altered the way whites thought about race.”

From an early age, Rudolph was aware of the fierce headwinds she and her family faced because of the color of their skin. Rudolph’s father was a railroad porter, and her mother cleaned white families’ houses while raising children in a basic wooden home with no electricity. Clarkesville was deeply segregated, and black residents were systematically intimidated and kept from good jobs and opportunities. The town’s tire factory was at one point forced to hire black workers but allowed them to work only the most menial jobs. Later in life, Rudolph remembered sitting on the grass across from the fairgrounds with other African American kids, watching white festivalgoers arrive in their fancy clothes.

“I was four or five then,” she later wrote, “and that’s when I first realized that there were a lot of white people in this world, and that they belonged to a world that was nothing at all like the world we black people lived in.” Because it was so dangerous to speak out, her parents implored her to keep her mouth shut, even when she saw gross injustice.

Rudolph also experienced the limitations imposed on women, especially in athletics. At the time, people believed that playing sports would make women look like men and prevent them from having children. In southern culture, ladies simply didn’t do such things—but Rudolph did them anyway. And she was among the first women athletes to be rewarded for it. According to Amira Rose Davis, an assistant professor of history and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at Penn State University, Rudolph helped gain acceptance for women as athletes, partly because she met the era’s beauty standards with her slim elegance and graciousness.

After the 1956 Olympics, she returned to Clarkesville a hero, and her high school hosted an assembly in her honor. She continued to play basketball and run track, earning a scholarship to Tennessee State. But in her senior year of high school, Rudolph got pregnant by her boyfriend and future husband, Robert Eldridge. She gave birth to their daughter, Yolanda, that summer. Fortunately, with help from her family, she was able to attend school. She was the first in her family to go to college.

After becoming a mother, Rudolph noticed that she was even faster than before. She struggled with starts but would quickly catch up and outpace her competitors in dramatic finishes that made crowds go wild. The key was in her calm and poise, both in and out of the stadium.

By 1960, Rudolph was in the middle of her college career and dominating the sport. In the lead-up to the 1960 Olympics, she not only won the AAU nationals in the 200 meters, but she set a new world record—22.9 seconds. At her first event in the Rome Games, the 100 meters, she was such a favorite that the crowds chanted her name—“Vil-ma, Vil-ma.” She won every race she entered: the 100 meters, the 200 meters, and, with Barbara Jones, Martha Hudson, and Lucinda Williams, the 4×100-meter relay, setting another world record. Rudolph was particularly beloved in Europe, and after her third gold spectators went ballistic. She was mobbed by microphone-wielding reporters, who dubbed her the fastest woman in the world. As one official told her after rescuing her from the scrum, life would never be the same again.

After the Olympics, Rudolph began using her celebrity to stand up for justice. Officials in Clarkesville wanted to host a homecoming parade in her honor. She told them that they could certainly organize an event but she wouldn’t attend if it was segregated. When she arrived home, black and white clubs and institutions alike marched in her honor. Her homecoming celebration was the first integrated event in the town’s history. But it would be a long road to begin to heal its racial divisions.

In the years that followed, Rudolph went on international goodwill tours and met ambassadors, famous entertainers, and even President John F. Kennedy. Her story of overcoming brought her renown worldwide, and the U.S. State Department used her as an example of the possibilities of democracy, belying the realities of racism in America. She continued to compete around the world and won nearly all her competitions until 1962, when she retired at 22 to spend time with her family.

Rudolph became more outspoken in her retirement. In 1963, after a monthlong tour in Africa, she participated in a multi-day sit-in protest at a restaurant in her hometown that denied service to African Americans. Many local whites responded violently. They jeered and threw things at the protesters. Townspeople hung a dummy dabbed with fake blood from an overpass to intimidate them, and someone fired gunshots into an organizer’s home, narrowly missing one of his children. Nonetheless, within a week, the city decided to desegregate Clarkesville’s restaurants.

“To talk about Wilma Rudolph, you have to talk about Jim Crow, you have to talk about racism in America, you have to talk about poverty and gender,” says Louis Moore, a professor of history at Michigan’s Grand Valley State University and author of We Will Win the Day: The Civil Rights Movement, the Black Athlete, and the Quest for Equality. “When we tell Wilma’s story, it’s not just to say, ‘Well, she triumphed, so can you, too.’ It’s also about being open and real about why so many people struggle who come from those backgrounds—backgrounds this nation created with Jim Crow and forced poverty.”

After her athletic career, Rudolph bounced around the country in various teaching, coaching, and youth-development posts. Like many African American women, she had a hard time finding sustained employment opportunities, despite her celebrity. Along with other athletes, including tennis pro Billie Jean King, she spoke out about gender parity in sports and the pay gap in athletics and elsewhere. In the eighties, she established the Wilma Rudolph Foundation to support young people in underserved communities through sports and academics. In 1994, at age 54, she died of brain cancer, survived by two daughters and two sons.

Over the years, Rudolph’s story has been celebrated in more than 20 children’s books. Her face has graced a postage stamp, a statue of her now stands in Clarkesville, and awards, buildings, and even a stretch of highway have been named for her. But perhaps the most fitting way her legacy lives on is in the resurgence of athlete activism in recent years and increasing opportunity for African Americans and women in athletics and beyond.

“If you drew a line from Wilma to today, you would certainly see that line curve toward progress in terms of availability of sports and the permissibility of women and girls playing sports,” says Penn State’s Amira Rose Davis. “But there’s still a lot of work to be done.”

You May Also Like

Generated Blog Post Title

February 28, 2025

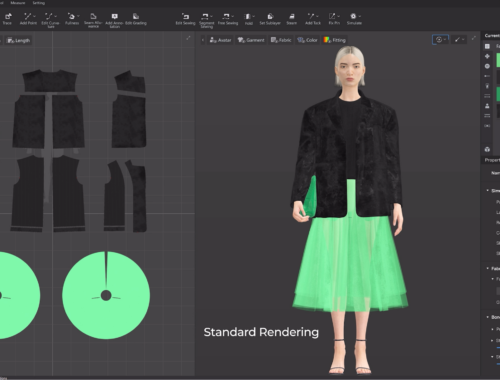

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025