How to Teach Girls They Don’t Have to Be Nice

Of course I want my daughters to be kind—but that doesn’t mean they can’t stand up for themselves

There’s one thing I want to tell my daughters as they start the new school year: You don’t have to be nice.

It feels heretical to write this. My husband and I try to raise our girls to be kind. “No matter what,” I remind them repeatedly, “be kind.” The note on my daughter’s teacher’s door reads: “Be kind whenever possible. It is always possible.” —Dalai Lama. There’s even a banner outside their public elementary school proclaiming it a Kindness Zone, an idea inspired by the bestselling kids’ book Wonder. The novel, which premiers in November as a much-anticipated movie of the same name starring Julia Roberts and Owen Wilson, has spurred conversations about inclusivity in classrooms across the country and made kindness cool again.

I love that.

But there’s a difference between being kind and being nice. Kindness comes from a place of inner compassion. Kindness can and should be taught. Niceness, however, springs from a desire to please others, even if it’s at our own expense. “For the most part, ‘nice’ means: Be tolerant and accommodating,” writes Shefali Tsabary, a clinical psychologist and author of The Awakened Family. “If we are brutally honest with ourselves, it also implies: Do whatever it takes to keep the peace.” Instead of teaching our girls to be nice, argues Tsabary, we should teach them how to be themselves, to be self-aware, “which means self-directed, self-governed, true to themselves.”

Not long ago, I found myself in a shouting match with someone I know well who suggested I ought to look more feminine. At first I was embarrassed that I’d lost my temper in front of my daughters; I regretted not taking the high road and biting my tongue for the sake of appearances. Only later, after the shame wore off, did I realize that by standing up for myself I am teaching them to assert their own strength and wisdom, to speak out when someone hurts their feelings, and to establish clear boundaries for what they will and will not accept.

Recently, a friend confided to me that her eight-year-old daughter had been touched inappropriately by a boy in her class. Rather than tell the teacher or her parents, her daughter carried her shame in silence. Only when she began crying in the mornings before going to school did her mother finally learn the truth. She hadn’t wanted to be a tattletale. She’d wanted to be nice.

Niceness won’t keep our daughters safe. According to Amnesty International, one in three women worldwide experience physical, sexual, or emotional violence in her lifetime; one in five experience rape or attempted rape.

Sometimes on the walk to school with my daughters, we role-play. They are seven and nine and almost ready to walk the three-quarters of a mile by themselves. I want them to have the freedom and the smarts to navigate our neighborhood safely without me.

“Pretend I’m a stranger in a car asking you for directions,” I say. “Do you stop walking? Do you go over to the car?”

“No!” they reply in unison.

“What if he says that I’m hurt or Daddy is, and that he’ll take you to us?”

“No!” they shout defiantly.

“What if the person offers you something to eat or says he has Pete?” (Pete is our dog.)

“Run away and yell!”

Together we practice roaring like an animal, the way I did instinctively years ago when a stranger attacked me on a hiking trail. As he approached, I felt obliged to smile and raise my hand in greeting. It would be rude not to. I was carrying four-month-old Pippa in a hiking carrier on my chest. He threw a rock that hit my head and narrowly missed hers. I learned that day that I do not need to be the friendliest person on the mountain. It’s OK, I remind myself and our girls, to walk on.

We pretend we’re lions or grizzly bears, making our growls deep and loud, not caring if people stare. We talk about sticking together, sharpening our elbows and ours senses, growing taller and stronger and walking faster, rather than shrinking, if they encounter someone who makes them uncomfortable. We talk about safe strangers—police officers, firefighters, schoolteachers—and safe, public places on their route to school. I remind them to pay attention and trust their instincts: If something doesn’t feel right, cross the street. My husband teaches them how to knee someone in the groin if they’re being touched, but never to walk toward that person. We talk about running fast and being alert and brave, not nice.

Does part of me feel macabre and creepy when we act out these scenarios? Definitely. But I know it’s riskier for me to drive them in the car than it is for them to walk alone. I tell them that it’s unlikely someone will try to hurt them, but it’s important to know what to do, to feel confident in their independence. Sometimes I wonder if I’m scaring them unduly, but then I remember that being slightly alarmist is far preferable to them being harmed. And that the world needs more girls gutsy enough to stand up for themselves and others.

Sometimes my girls bring home notes and drawings they’ve made in school. I smile when I find them in their backpacks and on the kitchen counter: “Kindness is always in fashion,” and “Kindness never leaves us. It stays with us wherever we go.” They’re reminders that we can be both tough and gentle at the same time.

You May Also Like

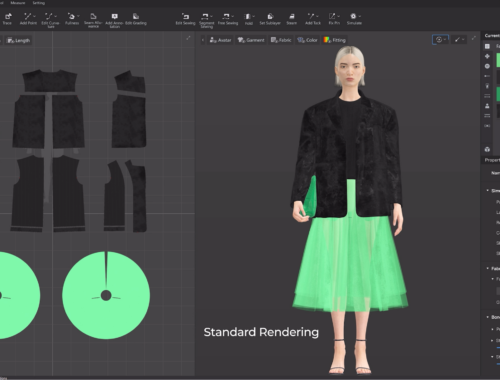

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

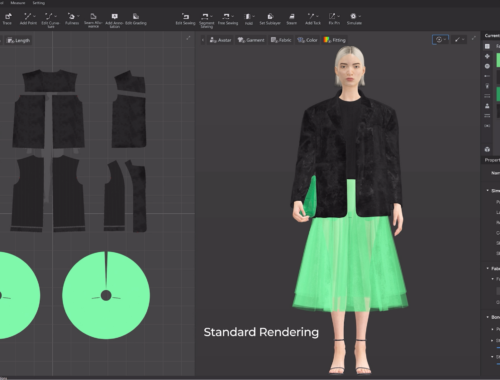

AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion

February 28, 2025