How to Make Cross-Country More ‘Extreme’

To re-invent itself, the sport should go back to its roots

On Tuesday, the International Association of Athletics Federations published a press release on the future of cross-country. From the sound of it, things are looking up for a sport that has long been overshadowed by the ratings juggernaut that is professional track and field. I couldn’t be more excited.

“The 2024 Olympic Games in Paris would be a fitting time to see the return of cross country to the Olympic program,” said IAAF president Sebastian Coe. The statement includes no clarification as to why it would be fitting, but of course everyone knows that the last time cross-country saw Olympic action was in Paris in 1924.

There’s just one problem. According to the IAAF, cross-country needs to become “edgier” and “more extreme” in order to gain a new audience and attract a “new breed” of runner. The press release doesn’t elaborate on how this might be achieved, except for mentioning that the course at next year’s World Championships in Denmark will include (hold on to your seat) the sloping grass roof of a museum.

Maybe I’ve become jaded after working at Outside for years, but the sloping grass roof idea doesn’t sound very extreme to me. It’s certainly not the kind of shit Vin Diesel lives for. If the IAAF really wants to bring more adventurous types to the cross-country fold, they’ve got to do better than that.

But how?

As is the case with any legacy product that wishes to remain relevant without losing its soul, cross-country must find a way to appeal to a contemporary audience while staying true to its roots. Easier said than done. There have already been murmurings among the cognoscenti that cross-country competitions might devolve into de facto obstacle course races in an attempt to attract the Tough Mudder demographic. From my unbiased perspective, that does not seem like a good idea.

Rather than filching from an event that always sounded like the world’s worst corporate retreat, cross-country’s best bet might actually be to take inspiration from its own glorious past. Retro running fashion is already experiencing a revival of sorts, so half the battle is already won.

Believe it or not, cross-country actually used to be more extreme without trying to be. In fact, the reason the sport had its Olympic status revoked after 1924 was because too many athletes DNF-ed in that race. This was largely due to the heat on that July day—temperatures exceeded 100 degrees—but the course was also not for softies. In his book, The Complete History of Cross-Country Running, Andrew Boyd Hutchinson notes that the terrain required athletes to navigate through "rough grass," as well as "heavy dust, thick weeds, and noxious fumes" from a nearby factory. Hutchinson also quotes Times journalists Arthur Daley and John Kieran's account of the race in their book The Story of the Olympic Games, wherein, "one runner entered the stadium gates in a daze, turned in the wrong direction and ran head-on into a concrete wall, splitting his scalp badly and falling to the ground covered with blood." Now, that's entertainment! These days, much cross-country racing takes place in the dull, safe environs of the country club. This needs to change. As a general rule, edgy stuff rarely goes down on a golf course.

I can hear the complaints already. Were the IAAF actually bold enough to bring back a less manicured type of race, weak-kneed coaches and athletes would moan about the risk of injury, or about how real runners are suddenly being deprioritized in favor of barbarians who enjoy charging through the brush. Such whimpering would probably leave an athlete like Allie Ostrander—a real runner if ever there was one—unimpressed. The young Alaskan is a collegiate All-American in cross-country and track. Every July Fourth, however, she races Mount Marathon, an out-and-back 5K that essentially entails running up a 3,000-foot mountain and throwing yourself off it.

If reverting back to a more natural type of course sounds like a slightly unimaginative way to give cross-country a little more oomph, perhaps the rules of competition should be tweaked. Here, too, innovation can borrow from tradition. Modern cross-country evolved from a game known as “hare and hounds,” which became popular in 19th century England. The way it worked was that a small group of schoolboys (the hares) would set out into the countryside and leave a trail of shredded paper for a larger group (the hounds) to follow. If the hares reached a predetermined location without being caught, they won.

Lovely. But a modernized version of the game could make one crucial adjustment: real hounds! People love animals in general, and dogs in particular. If the number of YouTube video views is a barometer of what counts as engaging entertainment—and, believe me, it is—adding animals to the mix is perhaps the most surefire way to acquire that coveted new audience. As for the old audience, who among my fellow distance running fans wouldn’t be intrigued by the prospect of seeing Galen Rupp chased across the heath by a crazed beagle?

Yes, there would still be some tiny logistical wrinkles to iron out. But as far as I’m concerned, hare and hounds redux represents cross-country’s best shot at avoiding obsolescence and giving track and field a run for its money as the nation’s 11th most popular televised sport during an Olympic year.

You May Also Like

Block Blast: The Ultimate Puzzle Challenge

March 19, 2025

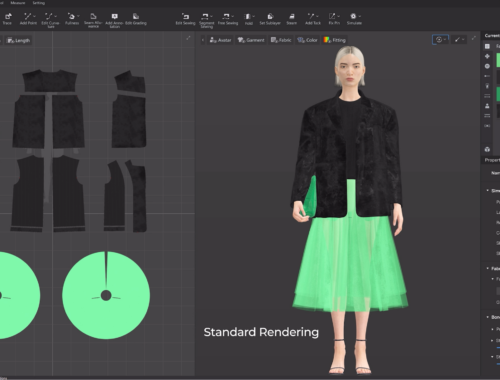

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Supply Chains

February 28, 2025