How Time Off Helped Hilaree Nelson Tackle Lhotse

The ski mountaineer was known for her relentless summits of the world’s toughest mountains. But the best thing she did for her career was take a break.

It’s hard to pin down Hilaree Nelson’s signature accomplishment. The 46-year-old was the first woman to climb two 8,000-meter peaks in 24 hours, and she has made first descents all over the globe, including all five of Mongolia’s Holy Peaks. She’s skied from the Himalayan summit of Cho Oyu in Tibet. She’s captain of the North Face Global Athlete Team. And she was named a National Geographic Adventurer of the Year in 2018. And yet, despite all these wins, Nelson’s greatest accomplishment might just be learning how to process failure. “I had a few years where a lot of expeditions didn’t go as I planned,” Nelson says from her home in Telluride, Colorado. “I was unhappy and totally out of balance and in a bad place in terms of the cycles of life.”

The difficulty started with Nelson’s attempt to summit and ski Papsura, a mountain in northern India locally known as the Peak of Evil. Nelson had been obsessed with the mountain for more than a decade, and she says her botched attempt to climb and ski it in 2013 triggered a series of failures in her life. The most high-profile of these was the 2014 expedition she led to the remote peak of Hkakabo Razi in Myanmar to determine if the mountain is truly Southeast Asia’s highest point. It was a logistical nightmare full of endless jungle hikes, hypothermia, dwindling rations, and porters who abandoned the expedition in the middle of the night. The adventure was the subject of a documentary, Down to Nothing, and Nelson still tours the country speaking about the lessons she learned. Following these professional frustrations, Nelson decided to do the unfathomable: she took a break.

For two years, she avoided ski mountaineering. She didn’t even leave the country. Instead she threw herself into new sports and purely athletic pursuits, like road biking and learning how to swim. She entered races and spent time with her two kids. “I had a lot of steam to burn off. I started running ultras and doing 100-mile bike races and Ironmans and climbing big walls,” Nelson says. “I spent time trying to sort out my life and get to the point where I felt mentally solid enough to put myself in the mountains again. Mountaineering is dangerous if everything goes right. If you’re not there for the right reasons, it’s even more dangerous.”

After Telluride’s good snowfall during the 2016–17 season, Nelson, along with her new expedition partner, Jim Morrison, began skiing technical couloirs in the San Juan Mountains, which required route finding, rappels, and navigating over and around big cliffs. It was a practice in technical ski mountaineering that gave Nelson the confidence to attempt tricky summits again—in 2017, Nelson and Morrison successfully climbed and became the first people to ski the Peak of Evil that she had obsessed over for so long. Nelson credits her accomplishment to the two years that she stepped away from her career. “That break gave me a whole new perspective,” she says. “Papsura was the first time I’ve ever gone back to a peak a second time. I was able to step out of this box and look at the mountain differently, find a different team, explore a different route, and target a different time of year. That wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t taken a break.”

Consider this Nelson’s second wind, a new era of exploration for the ski mountaineer. After Papsura, Nelson and Morrison put up a double summit of Denali, combining a sheer alpine climb up the 9,000-foot southern face of the Alaska mountain with a ski-mountaineering ascent and descent. But her most impressive feat might be her latest, when she and Morrison became the first people to climb and ski 27,940-foot Lhotse in September. Part of the Mount Everest chain and the fourth-highest peak in the world, it’s a prize that has eluded other ski mountaineers for decades, requiring a seamless ski descent after 18 days of climbing. She and Morrison decided to summit Lhotse in the fall, which meant they would train throughout the spring and summer, eliminating their opportunity to ski in preparation for an expedition that would require a massive, 7,000-foot ski descent off its face. “I wasn’t worried about the physical aspect of training for Lhotse,” Nelson says. “That tends to take care of itself, because I’m always outside doing something. But we made a point to hone the mental side of things leading up to Lhotse.”

Nelson says she and Morrison focused on climbing technique, from dialing in knots to scrambling escarpments, and made a point to train as often as possible in situations with high exposure, clocking ten-hour days in the mountains outside Telluride. “We’d go out to huge, rocky, 13,000-foot ridgelines where the rock sucks, and you’re scrambling, and you have to hang on and pay attention not to slip,” Nelson says. “We wanted to get used to the exposure and get used to working technical moves in high-risk situations.”

Nelson’s ski-mountaineering plans are sparse for 2019, but she has her sights set on the 9,000-meter peaks of the Himalayas for 2020. In the meantime, she’s diving deeper into the multisport approach. “It’s awesome to take up new sports later in life,” she says. “I didn’t think I’d like road cycling, but I love it. And I’m still in that sweet spot with where I’m getting better really fast.”

Her next goal: mixing things up on the slopes. “I’ve been skiing so much powder this winter, I’m thinking it might be fun to try it on a snowboard,” she says.

You May Also Like

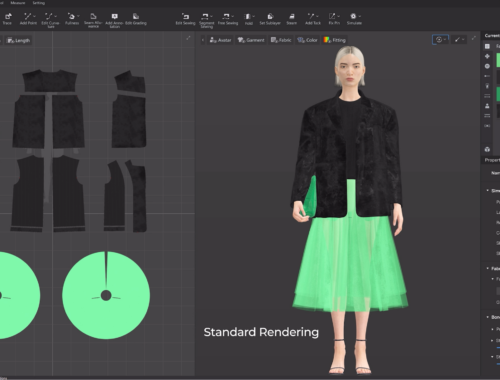

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for a Smarter Future

March 1, 2025

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Supply Chains

February 28, 2025