How Mike Foote Set an Obscure 24-Hour Skiing Record

>

Residents of Whitefish, Montana, were curious about why the ski resort just north of town left the lights on all night. Night skiing ended March 3, and now it was Saturday, March 17—Saint Patrick’s Day. If they had pulled out binoculars, they would have caught glimpses of a lone headlamp inching up Ed’s Run, a steep intermediate shot that drops right into the mountain village. That headlamp belonged to professional ultrarunner Mike Foote, 34, of Missoula, who was attempting to break the world record for most vertical feet climbed and skied in 24 hours.

Austrian ski-mountaineering racer Ekkehard Dörschlag set the existing record—60,350 feet—back in 2009. Foote was shooting for 61,200 feet with a plan to make 60 laps of the 1,020-foot Ed’s Run. At about 9 p.m. on Friday night, he was more than halfway done, with 31 laps under his belt in less than 12 hours. But the conditions were deteriorating as snow that had warmed and melted during the day began to freeze into chunks the size of small hailstones.

Foote’s skis were beginning to slide backwards on the last pitch of the run, which was the coldest, windiest, and steepest. His laps were gradually slowing down as his body started to show the effects of the more than 30 miles he had already skinned, all of it straight up. He’d built a buffer that morning under an unusually blue sky—Whitefish Mountain Resort is famous for its inversions—shaving more than two minutes from his projected average of 24 minutes per lap for the first 20 laps. By late afternoon, Foote had bought himself two laps’ worth of time—but now the knife was cutting the other way.

At the base of the run, Foote’s support crew of more than a dozen friends manned a folding table with homemade snacks and an assortment of fluids, like water mixed with Skratch Labs supplements and warm tea. Foote was burning an average of 500 calories per hour—twice what he consumes while running. His crew made sure to have a pair of skis waiting for him with skins already mounted so Foote wouldn’t have to waste a second during transitions. He skidded down from lap 31 and made a sweeping turn around a stake planted in the snow that served as the official lap marker. He popped out of one pair of 65-millimeter-waisted pink and green Dynafit race skis and stepped right into the next pair. Without a moment of pause, Foote stepped off.

A support crew member walked beside him for the first hundred yards, holding a bag of potato chips and a plate with boiled sweet potato slices, preopened energy gels, and bacon-and-rice balls. Foote gobbled as much as he could stomach, took a swig of Coca-Cola from a two-liter bottle, and said, “I should do this more often.” He mustered a half-smile and was off again into the night.

Foote grew up in Jefferson, Ohio, a town of a few thousand an hour east of Cleveland. The highest point in Ashtabula County is Owens Mound, which, at 1,150 feet, is not quite 600 feet higher than nearby Lake Erie. Needless to say, Foote was not born with hooves like his rivals in the Pyrenees and the Alps, or like his longtime friend and training partner Luke Nelson, a native Idahoan and a top-ranked American skimo racer and ultrarunner.

Foote didn’t start running in the mountains until 2004, when he moved to Missoula to study environmental science at the University of Montana. He had been a baseball player in high school, but out West he quickly developed a love of trail running and started competing in short races around Missoula. After working a few years as a raft guide in Glacier National Park and a ski patroller at Whitefish Mountain Resort, Foote moved back to Missoula and took a job at the Runner’s Edge, where he eventually became the race coordinator.

In 2009, Foote ran his first ultra, the Wasatch Front 100-Mile Endurance Race. “I had no expectations. I just wanted to survive,” Foote told me. He ended up finishing in the top ten. “I caught the bug then,” he said, “but I didn’t ever want to do a 100-miler again. It was horrible. Super painful. My body was destroyed. I just wasn’t used to it.” After that first 100-miler, Foote’s feet were so beat up that he didn’t run a step for six weeks. But he was hooked. In the years since, he’s finished second in the Hardrock 100 in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains three times and snagged two top-ten finishes in the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc 100, which runs through the mountains of France, Italy, and Switzerland. Now it only takes about a week of rest after a 100-miler before Foote starts running again.

Foote devotes his winters to high-intensity skimo races all over the world. The idea of setting a new vert record came to him in July 2017, after Hardrock. He wanted to do something on skis that would emulate the roughly 24-hour effort of a 100-mile race. It was only after he came up with the idea that he found Dörschlag’s record. “It was pretty esoteric,” Foote said.

His girlfriend, Katie Rogotzke, 30, a nurse practitioner who has completed a 50-kilometer race, captained his support team. “I was pretty incredulous,” she told me with a laugh as she changed out Foote’s skins between laps. Rogotzke said she never doubted him once he made the decision to train for the record. “He’s super steady. He likes faraway goals and getting into a Zen state of focus,” she said. “And the steeper the better.”

To prepare for the feat, Foote worked with coach Scott Johnston, who co-founded Uphill Athlete with legendary alpinist Steve House. Johnston said determining a race pace was the primary challenge in designing a training program for such a niche event. They settled on a goal of 2,560 feet per hour, including an anticipated average descent time of about 3.5 minutes per hour.

“Once we knew that was the race pace, we had to design a training schedule to optimize his physiology for that pace and develop his efficiency strategy,” Johnston said. Since Foote had such a depth of training experience from 100-mile and skimo races, Johnston said it was “just a matter of extrapolating” what they already knew about his metabolism and applying it to the unique demands of going uphill at a consistent grade for 24 hours. In the training jargon, Foote trained himself to become highly “monodirectional.”

“Rather than going out and doing shorter high-intensity work that’s faster than race pace,” Johnston said, “we needed to make him very efficient at that particular pace.” Foote’s training began last November and reached its apex in early February with two back-to-back 22,000-foot days at Montana Snowbowl, in Missoula. Foote stashed a duffel bag in the trees and set a skin track in fresh snow and banged out laps for about eight hours each day, proving to himself that he had the fitness to maintain race pace for at least a third of the distance, even alone and unsupported in less than optimum conditions.

Unfortunately, those two days took an unexpectedly severe toll on Foote’s body. “He didn’t recover well from the workout. It put him in a hole, and it took awhile for him to climb out,” Johnston said. “We had to go into emergency mode after that, but it’s a testament to Mike that he got the train back on the track again.” Johnston said he was confident Foote could’ve broken the 60,000-foot record then, and when race week finally came around, he told Foote, “The money’s in the bank. You know what you need to do.”

Foote said he had “a lot of nerves” on the day of the event and that he actually began to doubt himself during the first few laps. “I didn’t feel good at all. My heart rate was through the roof. It was just not clicking. I was sweaty,” Foote said. “But then I set into a groove. Having an aid station every 30 minutes forced me to eat and kept my energy levels constant.” The darkest hours of night were the most challenging, not least because the icy conditions forced Foote to yard on his poles to power through the final pitch, which was demoralizing in addition to creating an unanticipated energy demand.

By then, Foote had pacers leading him up the hill, including Nelson, which allowed him to turn off his brain and focus on putting one foot in front of the other. Foote’s community of support from his years as a ski patroller at the mountain paid off. The grooming machines came through and ran extra laps on the downhill portion of the run to soften the snow. At the beginning of the day, the downhill had been Foote’s only rest period. By 3:00 a.m., his quads were shattered, his feet were torn up, and he was screaming in pain with every turn on the downhills.

“When the sun started coming up, I started to feel good,” Foote told me, “or maybe I was just smelling the barn.” His pace had slowed to about 27 minutes per lap, but he was still barely within the window to complete 60 laps in less than 24 hours. When he finished lap 59, Foote officially broke the record with 60,180 feet gained. “The last couple of hours I thought, ‘I feel stable enough—this is probably going to happen,’” Foote told me from his bed at a nearby condo an hour after the finish.

“I felt a little emotional. I put a lot into this. It’s definitely one of the biggest goals of my life so far, and I was very much not confident that I’d be able to pull it off as the day approached. So I felt happy,” Foote said. “But I didn’t really have time to think about it, because we wanted to get an extra lap.” A dozen of his friends stepped off with him for the final lap, and with Nelson pacing him, Foote left them scrambling to catch up. Lap 60 was one of the fastest of the entire effort. He finished with five minutes to spare.

You May Also Like

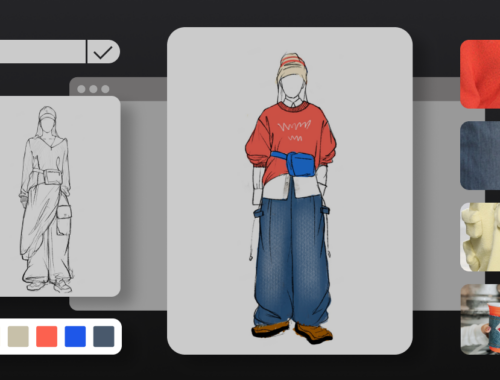

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

シャーシ設計の最適化手法とその応用

March 20, 2025