How an Olympic Runner Hits Race Weight

You can’t be super-lean all the time, so pick your moments—and watch your health

The least enviable highlight of Hilary Stellingwerff’s running career is that she barely missed being part of one of the dirtiest races in history. The Canadian middle-distance star finished sixth in her 1,500-meter semifinal at the 2012 Olympics, one place and an agonizing tenth of a second from an automatic spot in the final. Since then, six of the top nine finishers in that final, including the gold and silver medalists, have tested positive for drugs. She was robbed.

But that race was just one moment in a long and strikingly consistent career. Stellingwerff ran between 4:05 and 4:08 for 1,500 meters every year between 2005 and 2016, except for 2014 (when she was pregnant) and 2015 (when she ran 4:10 while returning from pregnancy). She ran 4:05 in three different years: 2006, 2012, and 2016—the latter two years corresponding with Olympic appearances, including a clutch 4:05 in that ill-fated Olympic semi. Stellingwerff delivered her best performances when the stakes were highest.

At a conference a few years ago, I got a glimpse of the meticulous approach behind her consistency and her ability to peak at the right time. Her husband and coach, Trent Stellingwerff, a physiologist at the Canadian Institute of Sport Pacific in Victoria, presented several years of detailed data on her body weight. It was a funny moment, as everyone in the audience silently (or audibly) wondered what would happen if they presented their spouse’s bathroom scale history to a roomful of strangers. But it was also very illuminating. There was nothing accidental about Hilary’s progression.

Trent has now published a fuller record of that data, updated through 2016, in the International Journal of Sport and Exercise Metabolism. It’s a rare peek at the nitty-gritty details of an Olympic athlete’s preparations—and an important opportunity to talk about a delicate topic, because body weight, sports performance, and health are interrelated in ways that lead to serious problems for a lot of athletes.

Let’s start with the most striking visual in the paper. The vertical axis shows the sum of eight skin-fold measurements, from which you can estimate body fat percentage. The horizontal axis shows time, with peak competition periods shaded. The stars indicate the lowest in-competition skin-fold measurement from each season.

It’s not a perfect sine wave, but it’s remarkably close. Hilary systematically allowed her weight and body fat to increase during each off-season, and then brought it back down for competition. The targeted weight fluctuations were on the order of 2 to 4 percent in each cycle.

Why does this matter? “Data is emerging to suggest that it is not sustainable from a health and/or performance perspective to be at peak body composition year-round,” Trent writes, “so body composition needs to be strategically periodized.” In other words, you can’t be race-fit all the time or you’ll get sick or injured.

One of the remarkable things about Hilary’s career is that she sustained only two injuries that caused her to miss at least a week of training. That’s astounding. Repeated DEXA scans during her career found that she had above-normal bone density. She had normal menstrual cycles (fewer than three missed periods per year) during a five-year period when she wasn’t taking birth control pills. Her iron levels were enviable, with average ferritin of 91 uG/L. For an elite endurance athlete who was apparently plotting her weight to the ounce, Hilary was strikingly healthy.

So how did the Stellingwerffs do it? Trent outlines some key practical points:

- They focused on the concept of “energy availability,” which involves estimating the calories required to fuel whatever training you’re doing plus meet your basic metabolic needs. During noncompetition periods, they made sure Hilary was meeting this threshold.

- To get down to competition weight—a number they settled on each year based on the accumulated experience of previous years—they took a gradual approach. They attempted to reach the goal in six to eight weeks, aiming for a daily caloric deficit of about 300 calories.

- The first tactic to achieve this caloric deficit was simple: Cut back on sweets and fat. They also periodized Hilary’s eating on a micro scale, ensuring that she was adequately fueled on hard workout days, but cutting back on snacks and carbohydrate portion sizes on easy training days.

- To avoid losing too much muscle during the weight-loss phase, they also ramped up the proportion of protein in her diet; Trent cites a goal of 2 to 2.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. This approach appears to have worked, as Hilary’s mid-thigh girth remained unchanged between competition and off-season measurements, despite an average 2.1 percent loss of body weight and a decreased body fat percentage from 12.9 to 10.6 percent.

There is, of course, a danger in trying to extract wisdom from or emulate the feats of Olympic athletes—especially since most of us don’t have an in-house physiologist to keep a close eye on our health. Weight is an extremely fraught topic, particularly (though not exclusively) for female athletes. Don’t get hung up on weight or make the mistake of equating “thin” with “fast.”

If anything, I think there are two useful messages to take from this. One is that whatever your “race weight,” you shouldn’t try to sustain it all the time. Give yourself periods of time when you’re a little heavier. (It’s even possible, Stellingwerff speculates, that training for part of the year while carrying a few extra pounds can offer an extra training stimulus—the equivalent of a weighted vest.)

The other takeaway is the idea of periodizing your food intake on a day-to-day basis in response to your specific training needs. As I noted in a recent piece, the current American College of Sports Medicine position statement on nutrition and athletic performance suggests that carbohydrate intake should be greater on hard training days and less on easy days—a practice that two-thirds of elite distance runners in a study earlier this year reported following, but as far as I can tell hasn’t really spread to the general public.

In the end, though, the biggest takeaway for me is incredible respect for Hilary’s career. I’ve known both Hilary and Trent for many years now and consider them friends, so I think it’s okay to say this: Hilary’s status as a two-time Olympian (and, in my eyes, an Olympic finalist) was never inevitable. As a longtime observer of the Canadian track scene, I’ve seen a lot of women come and go who had, on the surface at least, as much potential for world-class success as she did. But Hilary was the epitome of consistent progression and clutch performance. This case study gives one small window into the incredible amount of meticulous preparation and hard work that went into an amazing career—so congrats, Hilary!

Discuss this post on Twitter or Facebook, sign up for the Sweat Science email newsletter, and check out my forthcoming book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

You May Also Like

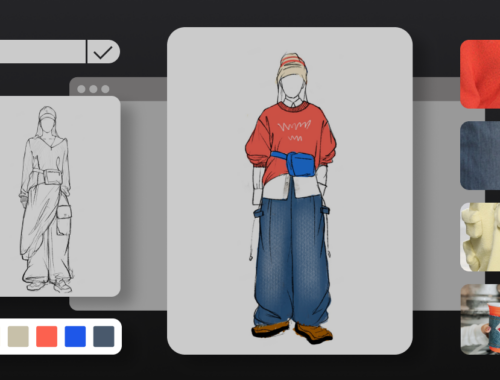

AI in Fashion: Redefining Creativity, Efficiency, and Sustainability in the Industry

February 28, 2025

AI in Fashion: Redefining Design, Retail, and Sustainability for the Future

February 28, 2025