Hikers Shouldn't Have to Pay Trail Fees

Click:98F32301008000

>

Trails in Wyoming are sorely in need of maintenance, so the state is considering a first-of-its-kind $10 annual fee for hiking on both state and federal land within its borders. Sounds reasonable and prudent, right? Well, by the state government’s own admission, it won’t work. That’s because, despite their good intentions, user fees don’t have the scale to adequately fund our public lands.

I love hiking, and you love hiking, so you and I wouldn’t have a problem paying $10 to go hiking. But aren’t you and I always trying to encourage other people to go hiking too? Fees, even relatively small ones, will discourage those potential hikers.

While an annual $10 fee may sound like a super-reasonable amount of money to pay for maintenance of local trails that you regularly use, imagine the potential impact on two subsets of users: the first-timer and the visitor.

Back in Los Angeles, I helped out at a local group home for underprivileged 17-to-21-year-olds by providing an outdoor mentorship program. The easiest, most regular thing I could do for those kids was take them hiking on our local trails. These kids often had zero experience in the outdoors, which made even a simple hour-long hike both challenging and intimidating. But you know what? After being forced along on a couple of my death marches, about half the kids started hiking on their own. That $10 fee would have limited my ability to run my little self-funded charitable endeavor (doing activities in multiples of 12 to 24 adds up quickly), and it likely would have stopped those kids from being able to take up the activity on their own.

I’ll give you another personal anecdote. My elderly parents just visited. They’re starting to suffer significant physical limitations, but I insisted that they had to come see the mountains near my new home in Montana. The one-mile hike took us well over an hour. Would I have paid $20 so they could complain a lot while walking a mile? Yes, but I also know plenty of people who would have balked at that price tag.

My point is that a fee that may sound reasonable to some will inevitably be burdensome to others. These are public lands we’re talking about, so by applying a financial burden of entry to them, we’re discouraging use of a resource purportedly owned by all of us. By limiting access to public lands, we’d also be limiting the number of people who care about those lands. By applying a user fee, we’d be decreasing the number of people wiling to vote to protect them.

Faced with budget shortfalls and maintenance backlogs, national forests in Southern California began charging a $30 annual user fee in 2005. The Adventure Pass immediately ran into legal challenges and today exists as a quasi-voluntary system understood by no one.

You see, federal law dictates exactly what the government can charge for on federal lands. The short version of the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act is that neither the Forest Service nor the Bureau of Land Management are permitted to charge for access on the lands they manage, nor are they able to charge for parking or access to unimproved features like scenic views. Crucially, they are also specifically barred from charging people to hike through those lands. What they can charge for is use of developed facilities, like picnic areas with tables, trash cans, toilets, and security patrols (under the REA, facilities must have all those features to merit a use fee), or camping at permanent campgrounds that have all those features.

It turns out the Adventure Pass couldn’t be required for parking at trailheads, using those trails, or stopping at an unimproved scenic overlook for a picnic. Due to the legal challenges, the Forest Service was also forced to remove much of its signage informing visitors that they were entering areas where the pass was required. And the penalty for failing to display the pass in a parked car became simply the $5 cost of a daily pass, and even paying that became optional.

Relevant to this discussion, the REA also governs what state governments can charge for on federal lands. Wyoming says it wants to apply its user fee to trails on both federal and state lands, so the state is going to run into the same legal issues that the Adventure Pass faced in California, at least on federal lands. States are free to charge for access to lands they manage, which is one of the reasons you don’t want states managing public lands.

By proposing such a low price—$10—Wyoming is tacitly acknowledging the regressive nature of user fees and trying to reduce their negative impacts (dissuading users) as much as possible. Of course, that also limits the fee’s potential revenue. State officials say they hope to raise up to $1 million annually through the fee. What will that achieve in terms of trail improvements? Not much.

Wyoming Pathways, a trail-access nonprofit, told Backpacker that it cost $250,000 to repair just six miles of trail this year. The state has about 10,000 miles of trails. At that rate, it’d take more than $416 million to repair all of the state’s trails. That $1 million will pay for 24 miles of maintenance annually—if all of the money raised from those fees goes directly to repairs.

We see this same problem elsewhere. Earlier this year, when the Department of the Interior proposed raising entry fees to $70 per vehicle at some parks, it calculated that the change would add $70 million to the National Park Service’s bottom line. Currently, the NPS’s $11.6 billion maintenance backlog is growing at a rate of $275 million a year.

How do we adequately fund public lands in this age of massive budget deficits? The Outdoor Industry Association asked exactly that question and commissioned Headwaters Economics, an independent public lands research group, to answer it. They looked at state-level funding programs across the country and came away with an assessment of what works.

Its conclusion? Tax-based voter initiatives that draw funding from stable sources and that enjoy broad bipartisan support. Those taxes cast a much wider net than user fees, while enjoying the support of the public.

How do you apply a new tax to benefit public lands without making it regressive or unpopular? Tax resource extraction on public lands. “The benefit of such revenue is that it does not directly increase the burden to taxpayers,” concludes Headwaters Economics, which also goes on to recommend other proven sources of additional tax income.

Wyoming is a state rich in federal land and the energy and minerals contained in it. Currently, the state government receives $1.39 billion annually from its slice of the federal government’s revenue on lands within the state. Those funds are spent on a number of worthy programs, like public schools and rural road maintenance, but the fact that not enough of that money goes back into fostering public access to public lands is a violation of the multiple-use principal upon which public lands are based. The U.S. Code says multiple use “means the management of the public lands and their various resource values so that they are utilized in the combination that will best meet the present and future needs of the American people.” Extraction is supposed to pay for public access—and it has the scale to do so, in a way that $10 user fees never will.

Congress just failed to reauthorize the Land and Water Conservation Fund, a tool that directed tax proceeds from offshore drilling directly to public lands access projects like trail maintenance. That cost the American public about $490 million in annual funding for stuff like Wyoming’s trails.

The problem isn’t inadequate sources of funding to pay for public land access; it’s the lack of political will to dedicate extraction income to its rightful use. Remember that when you’re voting next week.

You May Also Like

China’s Leading Pool Supplies Manufacturer and Exporter

March 18, 2025

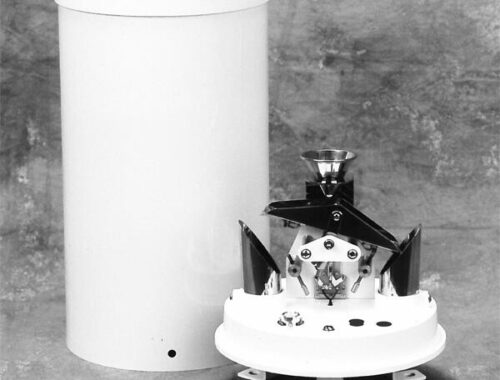

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025