Giving Mountains Back Their Indigenous Names

>

Last September, a 29-year-old Navajo climber named Len Necefer posted a photo of a young woman named Monserrat A Matehuala standing on the summit of Longs Peak, one of Colorado’s best known 14ers. What was significant was not that she summited—hundreds do each year. It was the location in the geotag that accompanied the post: Neníisótoyóú’u, the mountain’s Arapaho name.

BYs4kQilaZ3

The post was just one salvo in a quiet campaign waged by Necefer, a member of the Navajo Nation who now lives in Colorado. He earned his PhD in engineering from Carnegie Mellon, and then began working for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Indian Energy Policy and Programs. In March 2017, Necefer also founded Natives Outdoors. While it began as a social media effort to advocate for public lands and diversify the outdoor industry, it soon became something much larger. Today, Natives Outdoors makes gear (trucker hats, shirts) and works with athletes, brands, and organizations to spread its message.

“The creation of the first national parks, like Yellowstone and Glacier, was predicated on the forced removal of indigenous populations from these areas,” says Necefer. “It created this myth that these are untouched wilderness areas.”

When he first began his geotagging eforts, Necefer knew that Facebook’s check-in function had the option to create new locations. As an engineer, he also knew that Facebook and Instagram have an integrated back-end. So if he checked in somewhere on Facebook and created a new location through Facebook, it would generate a geotag for that location on both social media platforms. Meaning he could then take a photo, post it on Instagram, and tag it with the new location.

The idea for indigenous geotags first came to Necefer in early 2017, a few months after he had finished climbing the four sacred mountains of the Navajo Nation: Sisnaajini (Blanca Peak) in Colorado; Dookʼoʼoosłííd, Nuvatukya’ovi, and Wi:munakwa (the San Francisco Peaks) in Arizona; Dibe Ntsaa (Hesperus Mountain) in Colorado; and Tsoodził (Mount Taylor) in New Mexico. He had climbed the mountains for ceremonial reasons, but like most climbers, Necefer also came home with summit photos and was eager to share them on social media. “I wanted to share the photos and thought I would love to share them with the indigenous place names,” he says. “When I couldn’t find them, I decided to create them.”

By September, Necefer had expanded the project into the Colorado Front Range and began to involve his @NativesOutdoors Instagram followers and other Native American climbers in the project. On one climb, he and five other indigenous climbers summited Mount Belford, a 14,203-foot peak in Colorado’s Collegiate Range. Their summit photo, posted on September 7, tagged the mountain as Hiwoxuu Hookuhu’ee.

https://twitter.com/NativesOutdoors/status/909581330756841472

“The climb was nontechnical and straightforward,” says Necefer. And yet, he says, it was the first significant peak for many in the group, who grew up (like Necefer) not thinking that climbing was something that indigenous people did. “The more I researched, the more I learned that there were a lot of first ascents by Native people.”

This research, which Necefer describes as a blend of scholarly research and gathering traditional indigenous knowledge, led him to the work of Andrew Cowell, a linguistics professor at the University of Colorado–Boulder who worked with Arapaho elders to record traditional names for 300 locations across the western United States, including dozens within Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park. “The University of Colorado had a webpage, but it hadn’t been updated since 2004,” Necefer says.

Necefer has since worked to create indigenous place-name geotags for what he estimates as more than 40 mountains, most of them in and around Colorado. He also inspired Joseph Whitson, a non-Native student at the University of Minnesota, to launch another Instagram account, @IndigenousGeotags. That handle aims to use social media to educate Americans about the traditional indigenous lands where national parks now sit.

“I think Len’s work is incredibly important,” Whitson says. “Restoring names is a way of reclaiming not just the peaks, but all the cultural significance embedded in the names themselves.”

That effort is occurring offline, too. In Minnesota, for example, lawmakers plan to rename Lake Calhoun to its Dakota name of Maka Ska. In Washington, a proposal to rename Squaw Creek to Swaram Creek, its Methow name, has gained widespread support from both Native and non-Native groups, including the U.S. Forest Service.

Whether or not they’re successful, Necefer sees the project as a way of getting people tuned into a bigger conversation about the indigenous histories of wild places. “Once people see the names, they get curious,” he says. “It gives you just a little bit of information and can spark the interest in finding out more.”

You May Also Like

Essential Pool Supplies for a Perfect Swimming Experience

March 18, 2025

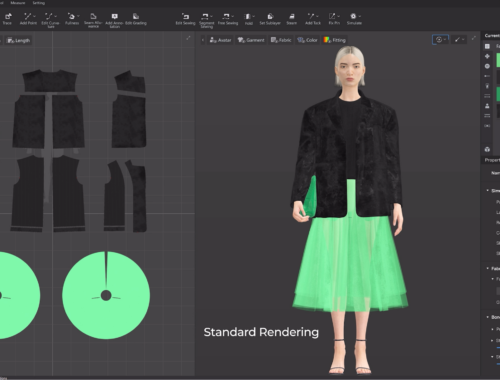

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025