Free Solo's Director Doesn't Give a F**k About Climbing

Filmmaker Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi doesn’t climb, but her determination to shine a light on what drives extreme mountaineers produced two of the best adventure documentaries of the past decade

“Today I was replacing swear words. I had to do it myself. No one else can do it,” documentary filmmaker Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi says over a nouvelle Indian lunch at bohemian-cool Pondicheri in Manhattan. She appears every bit the sophisticated New Yorker: elegant and slender, with an expensive-looking black leather jacket slung over her shoulder. It’s 98 degrees in the shade outside, yet she orders a spicy aviyal (a robust coconut vegetable stew) and a bowl of hot turmeric soup. And she enthusiastically accepts my offer to share my paneer dish and naan. She may look delicate, but I suspect she knows something about voraciousness.

Vasarhelyi and her husband, climber and filmmaker Jimmy Chin, codirected 2015’s narratively rich and visually jaw-dropping Meru, which chronicles the first ascent of the Shark’s Fin, a treacherous spire atop 20,702-foot Mount Meru in the Indian Himalayas. But the f-bombs to be replaced today occur in a not-quite-final cut of her latest collaboration with Chin, Free Solo. The film, which, in January, made the 2019 Oscar short-list for Best Documentary Feature, is about climber Alex Honnold’s pioneering 2017 ropes-free ascent of Yosemite’s El Capitan, a feat he accomplished in three hours and 56 minutes.

In the cut I saw in June, Honnold clocks four fucks in the first eight minutes. But Free Solo was funded by National Geographic—not especially fuck friendly. So before Vasarhelyi can fly out of New York City (where she primarily works and lives, along with the couple’s young son and daughter) to join Chin in Jackson Hole, Wyoming (where he primarily works and lives), she needs to scrub the cursing. “These guys,” she says, meaning climbers, “all swear.”

“It helped that she didn’t give a fuck about climbing,” says Jon Krakauer, a big fan of Vasarhelyi and the key talking head in Meru. That film is studded with moments of Krakauer explaining the culture of climbing and the danger involved in attempting such a peak, as well as the motivation for doing so—all facets Vasarhelyi strongly advocated for, to help make the film’s core alpinism accessible to a wider audience.

Still, her marriage to and collaboration with Chin has struck some in climbing as a collision of worlds, and their living arrangement is just one of the outcomes that raises eyebrows. “Everyone is like, ‘How do they do it with Chai in New York and Jimmy in Jackson?’ ” says Conrad Anker, one of the protagonists of Meru, along with Chin and Renan Ozturk. Then he adds, exasperated with the prying, “I don’t know how they do it, but they do it! They make it work.” (Vasarhelyi, too, is fed up with the topic. “Why does Jimmy say he lives in Jackson Hole? Because he doesn’t like New York and he often says he lives ‘just in Wyoming.’ Let him live ‘just in Wyoming.’ He’s in New York a lot.”)

During the three years between Anker, Chin, and Ozturk’s ill-fated attempt on the Shark’s Fin in 2008 and their successful redo in 2011, Ozturk was nearly killed in a terrible skiing accident and Chin miraculously survived a major avalanche. That’s all included in Meru, as are interviews with the climbers’ wives, girlfriends, and sisters—elements that existed in early iterations of the film but were reshot to bring up the emotional quotient when Vasarhelyi got involved. She helped break the mold of the typically bro-heavy genre of climber cinema and extreme-sports flicks in general. (See: the entire oeuvre of Warren Miller.) Meru delves into the fear and support that coexist in the families of these men. This, too, is largely thanks to Vasarhelyi’s influence. “It’s because I have skin in the game,” she says. In other words, because she’s in love with a guy who climbs peaks that might kill him, she needed to try to explain to herself the why of it.

“At Sundance for Meru, it was a completely different world for me,” says Anker. “I went from doing videos for Ernie’s Telemark Shop to being in a film that was a contender for the Oscars. On my end, it makes things easier—now we don’t have to do a film about my life. Chai and Jimmy did it already, we’re good.” It’s true: Anker shows up emotionally in Meru (“It was an eight-hour interview,” Vasarhelyi marvels), talking about his friendship with his climbing partner Alex Lowe, who died in a 1999 Himalayan avalanche, and how he fell in love with and married Lowe’s wife, Jenny, and adopted their three sons.

Honnold was in the market for a similarly definitive film when he began to contemplate free-soloing El Capitan. Nothing he was going to do as a climber would surmount that; El Cap is his godhead. “Chai brought a totally different approach to filmmaking than I’d experienced before,” he says on the phone from his home in Las Vegas. “Most of the time, in my other climbing films, you’re shooting for a brand—you go out and get the shot. You do it 17 times. Working with Chai was the first time I worked with someone who cared about getting the honest moment.”

By the time Honnold had begun to think seriously about El Capitan, he’d met Vasarhelyi only once. “It was at a North Face athletes summit,” he says. “A Giants game was on TV. An unnamed member of the team had edibles. I’d heard about this really smart woman from New York who was with Jimmy, this filmmaker—you know, Upper East Side, it’s pretty classy. And the first thing I said to her was, ‘Good to meet you. I’m completely incapacitated.’ I spent the whole Giants game with her.” After what Honnold describes as six months of courtship, he chose Chin and Vasarhelyi to film his climb. He knew they’d care for the story and be able to document the attempt in a way that wouldn’t compromise his safety.

“In a strange way, Chai and Alex are alike,” Chin says, calling from a surf vacation somewhere on the Pacific coast of Mexico, atop a bluff he climbed to get cell reception. “Her films are meticulously assembled. She doesn’t turn back until she’s tried everything. There’s a certain mentality of a climber in there—she won’t give up.

“It’s also about accuracy,” Chin continues. “It’s vérité. She has a certain level of restraint. You’re always tempted in filmmaking to play up or overstate something. Chai is intense and understated. She’s not tempted. She’s just like, nope.”

“I always wonder about the word intense,” Vasarhelyi says in a tone that indicates she doesn’t wonder at all. “Intense is used to describe women. Guys are intense, but they don’t get described that way.”

OK, but: she’s pretty intense. She’s only 39, and for her entire life she’s been living a high-octane, continent-spanning life in a family of intellectuals. The Vasarhelyis are old-school Upper East Siders, the kind of cultured meritocrats who defined that part of Manhattan before the hedge-fund managers took over. Chai’s parents, Marina and Miklos, were immigrants from Hong Kong and Hungary, respectively, who came to the States in the seventies to study and teach after meeting in California. (“I think the story was, he was the professor and she was his TA,” Vasarhelyi says.)

Growing up in Manhattan, she attended the Brearley School, which describes itself as a place for “girls of adventurous intellect.” She was good at science, a Westinghouse scholar. Her family’s apartment was steps from the Whitney Museum, and she says she spent many afternoons hanging out at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where her mother worked before she became the CFO of the New School. (She also worked at the Fashion Institute of Technology and Columbia University.)

When Vasarhelyi was 12, she cohosted a TV show on Nickelodeon called Totally Kids Sports. “You will never be able to find any footage of it. And that’s good,” she says emphatically. “It was Connie Chung’s heyday, right? They were looking for a nice Asian girl.”

Her dad, now a professor of business at Rutgers University, taught Vasarhelyi and her younger brother to ski—took them to Jackson Hole, in fact. He apparently taught them well. “Chai can drop Corbet’s Couloir,” says Chin, full of admiration. “She can show up in Jackson and rip the tram.”

Vasarhelyi started her film career while a student at Princeton, working in Hong Kong for the late ABC News anchor Peter Jennings. Her first documentary, A Normal Life, which was completed in 2003 when she was 24, followed seven college-age friends in Kosovo aching not just to live but to thrive in spite of the Bosnian conflict. “The only thing that separated us was circumstance, right?” says Vasarhelyi. “I had all these privileges. They never had those opportunities in a war that was supposed to be over.” A Normal Life won best documentary at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2003 and caught the attention of the late Hollywood director Mike Nichols, who hired Vasarhelyi as his assistant on Closer.

She spent much of the next decade working on films about Senegal. If you’re in Vasarhelyi’s personal orbit, you kind of have to love Senegal: “My brother has been three times, my parents have been three times,” she says. “I lived there for five years. Jimmy’s been to Senegal. Our daughter, Marina, went when she was a baby. We had a mosquito net around her Baby Bjorn.” Vasarhelyi’s documentary Youssou N’Dour: I Bring What I Love, about the great Senegalese musician, premiered at the Telluride and Toronto Film Festivals in 2008. Next came Touba, a “visual poem” of a film, in the words of one critic, that follows the annual pilgrimage of more than a million Senegalese Sufi Muslims to that city. In 2012, Vasarhelyi met Chin at a Summit Series conference (think Aspen Ideas Festival meets Coachella), where he was giving a talk on Meru and failure.

Long story short, part one: “We were standing alone right outside of where I was giving my talk, and I started chatting,” Chin says. “I said, ‘Oh, you’re a filmmaker. I’m about to give a talk. Want to come?’ And she blew me off and said, ‘No, I’m not interested.’ Which is totally Chai.”

But Vasarhelyi did put Chin in touch with a friend from childhood, Harvard professor and author Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, who was writing a book about creativity and failure and happened to be attending the conference, too. A connection among the trio was forged—“although,” Lewis says, “I immediately felt like the third wheel.”

Long story short, part two: “I was like, ‘Hey, do you mind taking a look at my assembly?’ ” Chin says, referring to his footage for Meru. At that point, the film had been knocking around for a couple of years, failing to get into Sundance and other festivals. “I sent it to Chai, and I didn’t hear from her for three months. I thought: (A) she doesn’t like me, and (B) she doesn’t like my film.”

Neither was true. Vasarhelyi was in Senegal during those three months, filming Incorruptible, a visceral look at violent clashes between students and the government of Abdoulaye Wade in 2012. When she returned to New York, she and Chin reconnected, began working on Meru, and fell in love. At the time, the project had a scant 35 hours of footage, including the climb and the interviews. It was Vasarhelyi’s idea to rewrite and reshoot, to “see whether Conrad, Renan, and Jimmy could access the emotions that were real.”

Krakauer calls the earlier version “a fine climbing film, just more kinda climbing porn. Chai turned it into a really good film, not just a good climbing film. It’s probably the best of the genre. Jimmy would agree with this.”

“That’s what she has, the sensibility of narrative and seeing ahead,” says Chin. “Sometimes she can see the film before it’s made. Also, understanding how the industry works. I have that capacity with expeditions. I don’t have that in the filmmaking world.”

Meru won the audience award for documentary at Sundance and received much critical acclaim. It also earned more than $2.4 million at the box office, making it one of the top-earning docs of 2015. Vasarhelyi talked Krakauer into being part of the publicity campaign; she was hoping for an Oscar nomination and playing the schmoozing game. She made the rounds with Krakauer, Chin, and Anker. But Meru didn’t land on the list for best documentary film. It was probably one of the few times in Vasarhelyi’s life that she came up short.

Meru at its core is about friendship, about its bonds and boundaries, and it’s clear that friendships were altered and came to an end through Chin’s collaboration with Vasarhelyi. At the time, Chin was still with Camp4 Collective, the production company he founded with Ozturk and photographer Tim Kempel. The three later recruited director Anson Fogel as a partner. Shortly after Vasarhelyi and Chin connected, Camp4 broke up for reasons that are still unclear but that seem to involve creative friction between Chin and the other partners and Chin’s desire to keep working on Meru.

The climber-filmmaker world is an insular place, with its own customs and ways. Vasarhelyi was considered an interloper. When I ask her about the whisper campaign that surrounded Meru—that she’s autocratic, that she was responsible for Chin’s Camp4 departure, she replies, “Hmmm. They say that? I really don’t have anything to say about it.” In 2015, Chin told National Geographic, “I’d prefer not to go into it, but I am happy to say that I founded Camp4 with Tim Kemple and Renan Ozturk in 2010. We brought in Anson Fogel a couple years later, and I left the company in 2013.” Fogel declined to comment.

Whatever resentments may remain in the climbing world, if Meru and Free Solo are any indication, her partnership with Chin will continue to produce great films. “We’re in a rhythm. We both know what the other person brings to the table,” Chin says. They each mention the connections they felt upon meeting: commitments to authenticity and storytelling and pushing the envelope, their shared Chinese heritage, even Jackson Hole. And professionally, they complement each other. Together their talents produce gorgeously shot films with an emotional core. As Chin says, “Worlds colliding works.”

Nowhere is that more evident than in Free Solo. Maybe the greatest paradox of the film is that it required a monumental operation that remained invisible. Five cameramen had to be ready to be in position on the wall on just a few hours’ notice, and there was a crew of three more on the ground. There was a helicopter for big sweeping shots of the wall and aerial shots of Honnold, a speck in a red T-shirt, shimmying up the white granite. He needed to be able to decide the time of the climb based on his intuition and readiness, not on some production schedule. He needed to feel free to bail. He wanted to be filmed, but he didn’t want to feel filmed.

“Alex told Jimmy at about five the evening before that he was probably going to go the next morning,” Vasarhelyi says. “Jimmy’s team was in position, but Alex had no idea they were in position.”

How was that even possible? How did they accomplish that? “By disappearing,” she says. “By making Alex feel that it was all good, whether he went or not.” It’s Vasarhelyi’s turn to be full of admiration for what her husband achieved. “They really played down the investment, the operation that was there. There were a lot of cameras—nine.” Some of them were mounted remotely near the most harrowing parts of the route. The crew couldn’t bear the thought of possibly filming Honnold falling to his death. Honnold couldn’t bear laying that responsibility on them. The stakes were high in every way. These people were intimately involved with one another.

“It’s why this film has captured the elegance of climbing. And of my process,” Honnold says. “I mean, they could have made some crazy, adrenaline-fueled, ‘He’s going to his death….’ ”

Nope. Vasarhelyi may not be a climber, but she cares deeply about the sport and had no interest in portraying Honnold as a risk junkie with a death wish—the way he’s sometimes treated by the mainstream media. The idea at the core of Free Solo, she says, “is this kid who is so scared of talking to other people that it was easier for him to climb alone, with no ropes, than to ask for a partner. I feel like we all have something in our lives like that. It was really important to see Alex’s eyes before he did it. What did his eyes look like the morning he set off?”

And what did the camera see? Vasarhelyi’s eyes light up. “He was excited.” Long pause. “And very well prepared.”

Lisa Chase (@lizziechase) is a writer and former editor for ELLE, New York magazine, and Wired. She is currently at work on a book about raising a boy on her own.

You May Also Like

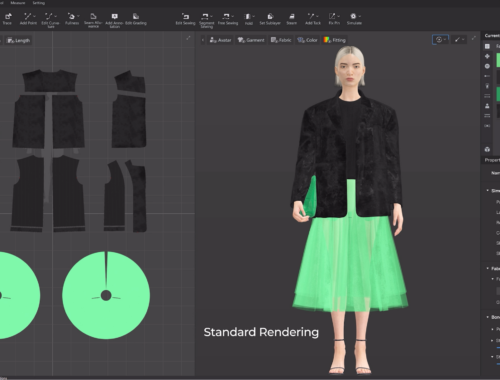

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

Monkey Mart: A Primate Paradise for Shoppers

March 20, 2025