Four Lessons from Two Harrowing Alaska Rescues

>

Climbing season is underway in the Alaska Range, with a recent run of good weather allowing a bunch of parties to make moves on their chosen routes on Denali and other peaks.

But with summit attempts also come rescues. So far, there have been four total (last year there were 19). The two most recent happened on May 20: one for a party of two on a sub-peak of Mount Hunter, within Denali National Park, and another for a two-person team on Denali.

Both were serious incidents, with high stakes. The Hunter pair was rappelling the Mini-Moonflower route when they were hit by falling rock and ice debris. Both climbers were cut and one broke their arm. The Denali rescue was even more harrowing. The two climbers were ascending a narrow ridge at around 16,500 feet, when they slipped and fell approximately 1,000 feet down toward the Peters Glacier, where they were stopped by a large, shallow crevasse.

What’s remarkable is that neither accident resulted in a fatality—and that’s because in both cases, the climbers (and rescuers) did everything right. On Hunter, the pair used an InReach, a two-way satellite messaging device, to request a rescue from the National Park Service, then they finished descending to the base of their route on their own and met the helicopter at the bottom. The Denali climbers used a similar personal locator beacon to relay their location to the NPS. Then one of the climbers hiked back up to camp at 14,200 feet and reported that his partner was injured but stable. She was later evacuated by helicopter and is being treated for significant spinal injuries.

In a statement, National Park spokesperson Maureen Gualtieri credited the successful outcomes in these two rescues to the “self-sufficiency of the climbing parties rescued; the use of satellite communication technology” and teamwork by the mountaineering rangers, volunteers, and guides.

There’s a lot to be learned from rescue scenarios like this, even if you’re attempting nothing more ambitious than a short hike on your backyard trails. We talked to Dale Remsberg—the technical director at American Mountain Guides Association who has experience guiding in the Alaska Range—about the key takeaways.

In the incident with the rock fall, the party had the skills to be self-sufficient in the first stages of the rescue. “They had the pre-requisite skills in terms of self-rescue to be able to get themselves off the peak. That’s not something every climber has,” says Remsberg.

Every person in your party should have a solid understanding of how to get out of a sticky situation—from knowing how to find the trailhead and using a first-aid kit to setting up improvised anchors and assisting an injured climber. “Before you go to a remote location, if you don’t understand self-rescue you should hire a professional to get you up to speed,” Remsberg says.

Don’t rely on cell service for communication in the backcountry. The outcomes of these two incidents would probably have looked very different if the parties hadn’t both had satellite communication devices. The first party had an InReach, which allowed for two-way messaging between the party and rescuers. “Being able to communicate back and forth can help rescue services decide what type of team to send and provide additional information about location, which can help reduce the response time and the risk to the search parties,” Remsberg says.

The second party is said to have had a personal locator beacon, but the type of device wasn’t specified. Some PLBs only allow one-way communication: users press a button that sends a rescue signal with GPS coordinates to dispatchers, who then relay it to the local rescue personnel. These tend to be cheaper than devices like the InReach and are a good emergency back-up.

But if you plan to go deep into the backcountry, Remsberg recommends carrying a device with the capacity for messaging. “If you just push a button that says ‘We’re in trouble,’ it doesn’t give a lot of information.”

“In a crisis there’s a perceived time pressure that you have to start speeding up,” Remsberg says. “That’s when accidents happen.” Even if there’s a significant injury, climbers should take a minute to pause and consider all of their options before they start executing a plan. Don’t make a bad situation worse by making rash decisions.

Given that the Denali climbers were said to be on a narrow ridge near 16,500 feet, they were likely just past the route’s fixed lines and ascending the exposed 600 feet of ridgeline around Washburn’s Tower. “This is a notorious area where climbers sometimes aren’t sure how best to tackle it,” says Remsberg. “It’s exposed and steep so people feel like they need to use the rope for protection.”

According to reports, the two climbers were roped together. “There’s a perceived notion out there, which used to be more prevalent, that you should always be roped together,” says Remsberg. “But if you’re roped together then if one person falls the other will also be pulled.”

It’s sometimes safer to climb unroped, according to the American Alpine Club. In situations where self-arrest is unlikely, like on a steep or icy slope, the “slip of a single climber roped to the rest of the team could result in the loss of the entire team.” Of course, the decision to unrope should take the climber’s skill levels and confidence into account.

Your Best Road-Trip Photos

You May Also Like

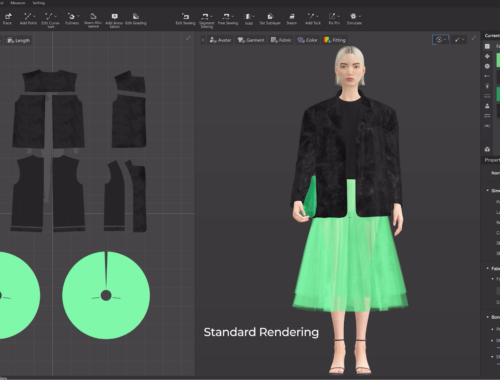

AI in Fashion: Redefining Design, Personalization, and Sustainability for the Future

March 1, 2025

Dino Game: A Timeless Classic in the World of Online Gaming

March 21, 2025