Finally, Congress Makes Progress on Fighting Wildfires

>

On Friday, Congress passed a $1.3-trillion spending measure to keep the federal government open through September, and it includes some major changes to how we fight, and pay to fight, wildfires. It’s about time.

In 2017, the government spent more than $2 billion on fire suppression through the Forest Service alone. The National Interagency Fire Center, the country’s wildfire planning headquarters, is predicting 2018 will be just as bad, if not worse. And with average wildfire size expected to grow six times larger by 2039, these blazes will get a lot more expensive. Here’s how the spending bill will help those efforts, as well as a couple ideas from experts on the next steps we need to take.

Since the Forest Fires Emergency Act of 1908, the Department of the Interior has been able to spend as much as it needs to fight fires during emergencies. That’s been helpful when the costs of wildfire season surpass the DOI’s $1.4-billion yearly fire-suppression allowance, but it’s meant dipping into Forest Service funds that should be spent on other important functions—such as maintaining trails, research, even forest-fire prevention.

“It’s a problem that’s causing a lot of people grief,” says Timothy Ingalsbee, executive director of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology, a group that advocates for smarter approaches to wildfire management. “If you’ve got a research project all set, or a recreation project for building trails, and all your funding is taken away at the last minute to pay for firefighting, that’s massively disruptive.”

The major fix inside the new bill allows the Forest Service to tap into disaster-relief funds, which are common for other huge destructive forces like hurricanes, floods, and earthquakes, instead of using up the agency's own money. The bill also raises the fire suppression piggy bank to $2.25 billion starting in 2020, with $100-million increases each year so that it reaches $2.95 billion by 2027.

An ounce of prevention

With the summer still a long way off, it seems hard to justify the unglamorous Forest Service work that keeps forests healthy and prevents minor fires from expanding into catastrophes. But prevention and the funds to support it are exactly what we should be focusing on. “The Forest Service is bipolar on fire,” says Dominick DellaSala, president and chief scientist at the Geos Institute, a group of researchers studing how the country should prepare for climate change. “When fires aren’t burning, they talk about managing it for ecosystem benefits, and during the season, they’re throwing everything at it.”

Though wildfire prevention is a hard sell this time of year, public attitudes tend to shift rapidly in the next six months, when images of smoke and flames are broadcast over TV and Instagram. By August, authorities are often compelled to use expensive resources like air tankers and helicopters to show the public they’re on top of things.

“Americans are big hearted,” says Steve Ellis, vice president of Taxpayers for Common Sense, a non-partisan budget watchdog based in Washington, D.C. “We see a disaster, and we want to assist. We want the government to assist. But that means we can’t afford to be softheaded in anticipation of that. You want to see the right priorities from the start, and to be sure that it’s not so rigid or static that the Forest Service can’t still meet their needs as smaller changes develop.”

Ellis and DellaSala hope to see new policies that would encourage the Forest Service to dedicate more resources to off-season mitigation. They’d also like to see the Forest Service take a fire’s size, momentum, and proximity to human structures into account more often when deciding what to do about it. This would mean allowing smaller or more remote fires to burn, or steering them toward places that could benefit from them. Low-intensity fires are part of a forest’s natural cycle and are essential to enriching the soil with nutrients, reducing competition between larger trees, providing necessary heat for seeds to germinate, and allowing smaller plants better access to sunlight.

Stop building homes in the woods

Congress could save taxpayers a fortune in the long run if it passed laws aimed at reducing development along the wildland urban interface, encouraging local and state zoning codes that reduce the damage wildfires can do. The government could also offer more incentive to get people to take precautions. According to one study, as many as 90 percent of residential structures survived a wildfire if they maintained at least ten yards of fuel-free area around the home. Rewarding local governments that encourage fire-smart living—for example, by offering property tax rebates to homeowners who maintain a fuel-free zone—could off-set millions in future costs.

Listen to Smokey

Humans accounted for nearly 90 percent of all wildfires from 1992 to 2017, according to an article last year from the National Academy of Sciences. As our cities and towns push into wilderness, and as we escape to public lands to get out of our cities, it’s essential we take our role in fires more seriously.

Smokey the Bear had it about right: fighting fires is on all of us.

You May Also Like

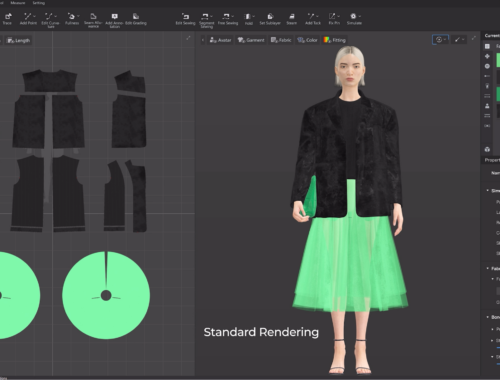

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

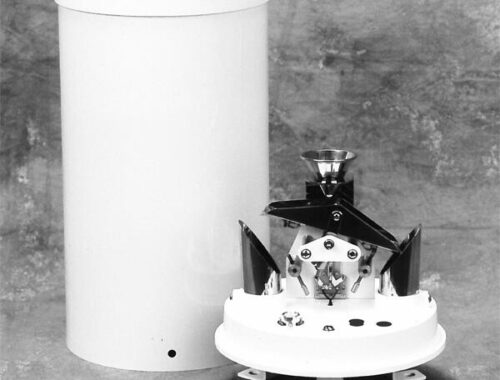

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025