Federal Employees Are Living in Fear

>

The most surprising emotion I’ve encountered while reporting on the partial government shutdown? Fear. Everyone from park rangers to administrators to government lawyers to guides who operate independent businesses on federal land are all too scared to publicly go on the record about how the shutdown is impacting them. And let me tell you, that is anything but normal.

It didn’t used to be this way. Last March, when I set out to report a story about human poop winding up in glacial water sources, I looked up a government scientist’s cell number (fun fact: many government employees have their mobile numbers listed online), dialed it, then had an hour-long chat with the guy while he drove his kid home from school. It sounded like it made his day to pick up the phone to find a reporter who’d read his research and wanted to talk about poop on the record.

In August, when I was reporting on the economic impacts of the Ferguson Fire in Yosemite National Park, I had to be careful about the number of voice mails I left with park employees, because they were all calling me back so fast and so often that it was getting in the way of my ability to actually finish a conversation with anyone.

And all that was totally normal. Government employees serve the public, so as a reporter, I’m used to being able to call them up and get someone on the line whose job it is to share their work with me.

Then something changed.

The first week of the new year, a friend forwarded me an e-mail from someone who’d overheard a rumor that a man had died in Yosemite over Christmas. This was before any deaths had been reported in a national park during the shutdown, and I figured it merited a good story, so I called the park’s headquarters. The woman who answered sounded bright and cheerful, until I told her I was a reporter looking into an unreported death. She quickly connected me to a desk that never picked up, and my voice mails were never returned. I didn’t think too much of that; after all, 80 percent of park-service employees are furloughed. But then it took a solid six hours of cold-calling anyone I could find, with any link to the park—even a teenager who’d been visiting Yosemite on the day of the death—before I got ahold of someone with knowledge of the incident who was willing to talk to me. But only off the record.

That person relies on their relationship with the Park Service in order to operate their business. And they’d picked up on the vibe that the Park Service didn’t want anyone talking to outsiders about park business during the shutdown. “I can’t have my name anywhere near this,” my source told me.

Frustrated, I reached out to the Association of National Park Rangers. It didn’t respond. I started hitting up various “Alt” Park Service Twitter accounts and had a few bites and a few intros made to potential subjects. But none of those subjects were willing to talk.

In the middle of my reporting efforts, President Trump sent out another bizarre tweet, accusing California of not managing its forests properly, and I got the idea in my head that, with the U.S. Forest Service furloughed, the federal government might be falling behind on its fire-prevention work in that state. My layperson’s understanding of controlled burns is that they need to take place in winter, when it’s raining, which is an increasingly rare occurance in California. But a string of storms is currently hitting that region. Did that mean the shutdown was getting in the way of effectuating controlled burns? I needed confirmation from a professional. With no one at regional forest-service offices picking up, I got the cell-phone numbers of a few hotshots from a friend and started calling around.

I needed someone with knowledge of controlled burns to tell me if conditions conducive to controlled burns were occurring during the period of the shutdown and confirm whether the Forest Service is unable to perform controlled burns due to the shutdown. But while I got ahold of several on-duty firefighters, only one of them would actually answer my two very simple questions and, even then, only after reassurances from a mutual friend that I wouldn’t out his identity.

I then spoke with an EPA lawyer who was furloughed; she, too, was scared of losing her job if she revealed her identity. The interview needed to remain anonymous. “As I’m sure you’ve gathered talking to other people, this is a particularly sensitive administration,” she told me. Now, if someone who’s working for much less money than she’d earn in the private sector (because she truly believes in her agency’s mission) is scared that she’ll be fired for revealing she’s worried about missing a student-loan payment due to the shutdown, something is profoundly broken.

“When a culture of fear and reluctance to engage with the public has reached such a level that even frontline firefighters and park rangers doing taxpayer-funded work are afraid to engage with the public that they serve, then we have real problems,” says Outside reporter Elliot Woods, noting that he’s encountered a similarly surprising reluctance among public employees to go on the record—if they’re prepared to talk at all.

No Park Service employee, let alone a third-party contractor, should be scared to reveal that someone died in a national park. The public needs to know that information, as well as the reasons for the death, in order to make informed choices about their own safety. Transparency also helps the Park Service operate its lands to be safer and better serve the public. No ranger should be afraid of sharing their feelings about some of our most famous parks being irrevocably damaged by neglect. We pay them to care about these areas and help us preserve them for future generations. If that ranger is struggling to put food on the table due to the actions of our publicly elected leaders, that’s also something voters need to know. And no firefighter should be scared to say we’re blowing a golden opportunity to prepare for this summer's wildfires.

That all these people are scared to speak is simply wrong. This is not how our government is meant to function.

You May Also Like

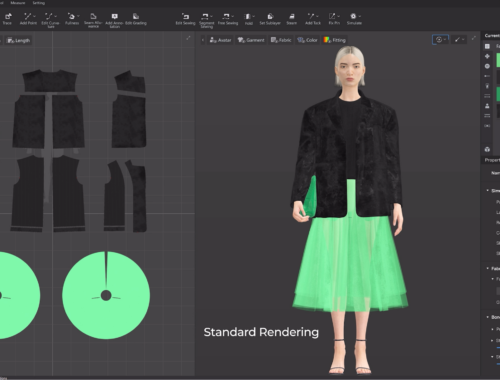

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025

AI in Fashion: Redefining Design, Personalization, and Sustainability for the Future

March 1, 2025