Eliud Kipchoge Just Broke the Marathon

A stunning world record of 2:01:39 resets our understanding of what it means to run 26.2 miles.

For a few moments on Sunday morning, I wasn’t sure who was more tired, me or Eliud Kipchoge. I had slept restlessly in the basement and set my alarm for 4 a.m. so that I could watch a grainy live stream of a bunch of bantamweights running a marathon through the streets of Berlin. Kipchoge, the 33-year-old reigning Olympic champion from Kenya, had just breasted the tape. But instead of wheezing or collapsing to the ground or even breaking stride, he had pounded his chest a couple of times, surged across the line—and then accelerated, pumping his fist and slapping his forehead in disbelief before leaping like an amorous bride into the waiting arms of his longtime coach.

I was awake, albeit puffy-eyed, because I knew there was a chance Kipchoge would do something ridiculous, and that if he did and I only found out after the fact, the world would already have changed such that whatever he did would no longer seem impossible. I wanted to experience the transition between wild hypothetical and established truth in real time. And (in case you haven’t seen the news) that’s exactly what happened. Kipchoge ran 2:01:39, slicing a stunning 78 seconds off the previous world record, by far the largest margin for more than half a century in an era of supposedly diminishing returns. After watching Kipchoge sprint around in celebration for a few minutes, I flicked off the iPad to get a few more hours of sleep before my kids kicked into gear. But I found that, like the man himself, I was too wired to slow down, so I lay there with my mind spinning about the new world we’re living in.

Last year, Kipchoge participated in Nike’s controversial marathon-slash-marketing-stunt-slash-science-experiment, Breaking2. After years of preparations and millions of dollars, everything was optimized: the course (a Formula One racetrack in Italy), the weather (the date of the race was only finalized a few days in advance, once good conditions were assured), the footwear (a new shoe that, according to Nike’s testing, makes runners 4 percent more efficient), and so on. Perhaps the most crucial detail: Kipchoge and two other runners were sheltered for the entire race by six pacemakers running in a tight arrowhead formation—a violation of world record rules, since fresh pacemakers joined the race partway through.

Under these hyper-optimized conditions, Kipchoge ended up running 2:00:25, which was short of the sub-two-hour goal, but well clear of the official record of 2:02:57 and miles ahead of what most pundits had predicted was possible. That set off two debates, one obvious and one less so. The obvious debate focused on what Kipchoge’s 2:00:25 equated to under legitimate record-eligible conditions. How much was the drafting worth? The shoes? The myriad other details that Nike had finessed? But the more subtle debate looked instead to the future. What, if anything, would the Breaking2 performance mean for future runners in regular marathons? Had Kipchoge’s stunning run somehow altered the horizons?

The latter possibility was, in fact, one of the stated aims of the Breaking2 team. Seeing a human run under two hours (or, as it turned out, just over two hours), they said, would change our perspective and break down mental barriers, allowing subsequent runners to go faster under normal conditions. I initially found this argument unconvincing, but the more I spoke with Kipchoge, the more I started to believe it. “The difference only is thinking,” he told one reporter. “You think it’s impossible, I think it’s possible.” And then, standing trackside at the Formula One circuit in Monza in May 2017 and watching Kipchoge flirt with the two-hour barrier, it began to seem real to me.

Last September, I wrote an op-ed for the New York Times in which I argued that the 2017 Berlin Marathon, Kipchoge’s first post-Breaking2 race, would be “a real-life test of the ‘mental barriers’ theory of human endeavor.” Having run 2:00:25 in Breaking2, Kipchoge would sweep aside the old world record with ease. My prediction at the end of the article: “I think he’s going to run 2:01-something.”

Then it rained. Kipchoge’s sodden winning time of 2:03:32 was still the seventh-fastest of all-time, a stunning performance but not a record. Seven months later (elite marathoners can rarely manage more than two supreme efforts a year), he tried again at the London Marathon. This time it was the heat, with temperatures of up to 75 degrees making it the hottest day in the history of the race. Again, Kipchoge won handily but fell short of the record. And as the months ticked by, I worried that the sands of time might be running low for Kipchoge, who will officially turn 34 in November but is rumored in some quarters to be several years older.

This year, when Michael Joyner, the man whose 1991 journal article presaged the possibility of a two-hour marathon, called for predictions a few days before the Berlin race, I was circumspect. I predicted 2:02:52, just a few seconds under the old record—which, as it turns out, was the most popular range of predictions—and I thought I was being optimistic. Only seven of the 70 respondents to Joyner’s poll predicted sub-2:02.

On Sunday morning, Kipchoge had just passed the 10-mile mark when my alarm roused me. I’d gambled that nothing interesting would happen in the first 10 miles, but I was wrong. Already, two of Kipchoge’s three pacemakers had unexpectedly dropped out, leaving him with very little opportunity to draft—one of the key advantages thought to have made his Breaking2 run possible. The third pacemaker lasted only until 25K, at which point Kipchoge was left to fend for himself for the last 17 kilometers (just over 10 miles) of the race. The commentators on the race broadcast worried that Kipchoge might accidentally accelerate once the last pacemaker dropped out, burning up precious reserves that would force him to slow down in the final miles. They were half right.

From 25 to 30K, Kipchoge did indeed accelerate, running 14:21, seven seconds faster than his previous 5K split. But instead of slowing, he then got even faster, running 14:18 for the next 5K. It became increasingly clear that he wasn’t going to hit the wall. He’d passed the halfway point in 1:01:06, very close to his seemingly suicidal pre-race plan of 1:01:00. He ended up running the second half, mostly by himself, in 1:00:33—a half-marathon time that only four Americans in history have bested. Superlatives are inadequate to express how crazily incomprehensible this is.

Here’s what sticks with me, now that I’ve had a full night’s sleep to mull it. First, I think you can draw a direct line between 2:00:25 at Breaking2 and 2:01:39 in Berlin. This is not to claim that marathon performance is “all in your head,” or that we’d all be capable of running 2:01 if we had Kipchoge’s self-belief. Far from it. But I have a hard time imagining Kipchoge requesting that his pacemakers hit the first half in 1:01:00 without having, in some artificial sense, been there before.

But can anyone surpass this mark? Right now, Kipchoge is the only human on the planet who can honestly tell himself that he’s capable of running in the 2:01s. But history tells us that others will come, and Kipchoge’s trailblazing will make it easier for them to follow. In fact, the failure of the pacemakers suggests that the new time isn’t even the full measure of Kipchoge’s own potential. Various attempts to quantify the benefits of perfect drafting have pegged the time saved as roughly four minutes over the course of a two-hour marathon. Even if that estimate is too generous by a factor of two, having multiple pacemakers to 35K instead of a single pacemaker to 25K might subtract another 30 seconds or more.

I take that estimate with a big grain of salt, though, because you could also imagine that having more pacemakers might somehow have messed with Kipchoge’s rhythm or held him back. Maybe Sunday’s race was as perfect as it gets for Eliud Kipchoge. And maybe this record will stand for 10, or 20, or 50 years.

But I wouldn’t count on it. Now that we’re this close to the two-hour barrier, I’m guessing its allure will exert a steadily stronger gravitational pull, sucking more and more money, effort, and attention toward the chase for immortality. Breaking2 showed what can happen when all the variables are optimized; some of those lessons can be repurposed for a marathon held under record-eligible conditions. Maybe there are faster places than Berlin for a marathon (Joyner suggests the Yuma Proving Ground); maybe money can buy better pacemakers than the ones who faltered on Sunday. Maybe there are more ways of optimizing the weather, the clothing, the drinks, and everything else.

I’m excited about that prospect; it’ll be fun to watch. Still, I have one nagging doubt. What if it was all Kipchoge? What if, despite all the tweaks and innovations, the marathon hasn’t changed at all? In a way, that would be the best outcome, because it would give us the unique generational bragging rights of having had the opportunity to watch the greatest of all time at his peak. That possibility, in the end, will keep waking me up before dawn a few mornings a year for as long as Kipchoge keeps running.

My new book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on Twitter and Facebook, and sign up for the Sweat Science email newsletter.

You May Also Like

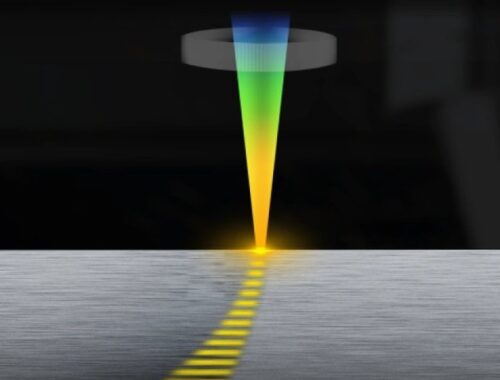

HOW TO IMPROVE PRODUCTION EFFICIENCY OF A LASER PLATE CUTTING MACHINE

November 22, 2024

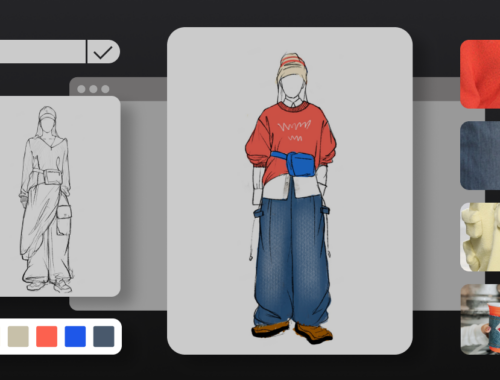

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025