Climber Eva López Has a PhD in Finger Strength

>

In the climbing world, there’s no shortage of options for planning your training. But Spanish climber and coach Eva López’s program, sold with her training boards, might be the most thoroughly tested. After all, it was the subject of her PhD thesis.

López, 47, lives in Toledo, Spain. She first got on the wall in 1990 and has continued to push herself by training constantly and pulling on hard routes. In 2005, she became the fifth woman to climb 5.14b. In 2014, at age 43, López put down her most difficult route to date, the 5.14c Potemkin, in Cuenca, Spain. Her passion for climbing led her to the lab at University of Castilla–La Mancha to develop research-driven training methods for climbers. “My experience as a climber told me that it made sense to start with one particular key factor: finger strength,” López says.

When she started her research, the existing scientific literature indicated that—perhaps unsurprisingly—finger strength was the most important factor in climbing performance. But what’s the best way to build that strength? López has now published three papers on finger training that help answer this question.

In her research, López tested how finger strength changed over the course of an eight-week training program using different types of interventions, such as hanging on tiny edges or by adding weight. To measure finger strength across the program, she noted the maximum weight elite climbers could carry—in the form of weight added to a harness—for five seconds while hanging from their fingertips on a wooden 15-millimeter edge. Across her three studies, López worked with a total of about 100 climbers. The results suggest that a relatively short, maximum exertion–based program is an effective way to quickly build finger strength.

López integrates her research findings into her training program, which instructs climbers to exhaust themselvesover a short period of time by hanging on the smallest edges possible or with added weight for just seconds at a time. López released the routine in 2011, along with a correspondingtraining board called the Transgression (and a gentler version called the Progression), which has a series of horizontal edges decreasing in depth from top to bottom. Most hangboards feature an assortment of edges, pockets, and sloping holds, but the Transgression is unique in that it’s tailored to systematically train fingers.

López’s finger-training routines are short, requiring just ten to 20 minutes per session. Over the course of four to eight weeks, participants first cling from edges with the most weight they can hold for ten seconds, usually using weights attached to a harness or belt. In the next half of the program, climbers switch to maxing out not with weight but with the tiniest edge possible.

The routine initially sparked some skepticism among climbers. It was more common at the time to train by hanging for long intervals using holds that were below a climber’s physical limit. “López’s training programs really reduced the volume quite a bit over what had become popular in the training world,” says Kris Hampton, a coach and the owner of Power Company Climbing. “A lot of people early on thought it was just not enough to be effective. You’re generally only doing 30 total seconds of hanging.”

This apprehension has since faded: López’s program is now widely embraced in the climbing community, and many pros have used her approach in their training. Nina Williams, known for her ropeless ascents of difficult 40-foot boulders, finds López’s research-backed program “hugely appealing” and has been using the Transgression board since 2014, with one or two four-to-six-week cycles of the program per year. “I have seen a large increase in finger strength and overall climbing performance,” Williams says.

Despite her program’s success, López is quick to point out that her work “is just a grain in the desert.” She says that replicate studies need to be conducted using climbers of varying skill. (Her subjects are usually elite-level athletes.)

In the future, López wants to grow as both a climber and trainer. She suffered a shoulder injury in 2015 but hopes to fully recover and reach her long-term goal of climbing 5.14d. She also wants to write a book on training, which would use current research—including her own—and her 25 years of experience as a coach to recommend methods to build finger strength and improve climbing performance. López’s main concern, she says, is that there’s always more to learn. “I would never know when the book would be finished.”

How to Change Your Oil

You May Also Like

Anemometer: The Instrument for Measuring Wind Speed

March 20, 2025

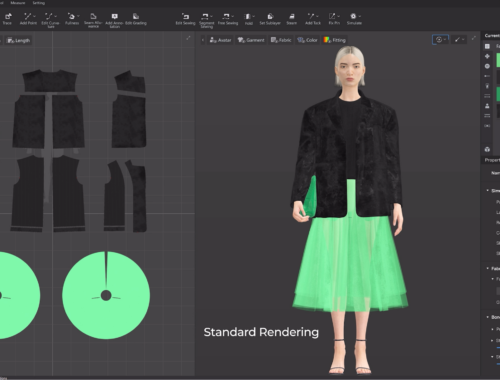

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025