Canada’s Unemployment Crisis Hits Gen Z, Women, Quebecers Hardest

MONTREAL ― The April jobs report from Statistics Canada was worse than any in living memory, but sadly, that 13-per-cent unemployment rate isn’t even half the story.

It’s an artificially low number. Anyone who’s lost their job but isn’t looking for work doesn’t get counted as unemployed. Take into account all the people who have dropped out of the workforce since the pandemic took hold ― about 1.7 million people ― and Canada’s unemployment rate would be closer to 20 per cent.

Watch: Pandemic’s harm to women’s employment will affect recovery, Trudeau says. Story continues below.

Add to that people who have lost hours and income at work, but are still officially employed, “and a shocking 29 per cent of those working in February had lost their job or the majority of their hours by April,” economist David Macdonald wrote on the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives blog.

But ― as is always the case in economic downturns ― the pain isn’t spread evenly. Certain groups, and certain regions, are taking a large share of the pain.

Generation Z

While COVID-19 has disproportionately targeted the elderly, it seems it’s the people at the other end of the age spectrum who will suffer most from the crisis’ economic fallout.

“Recessions are never kind to the younger generation of workers, but the current one has been particularly cruel,” TD Bank economists Beata Caranci and James Marple wrote in a report Friday.

They’re not exaggerating. If anything, calling it a recession is an understatement for working youth. Generation Z, the cohort now entering the workforce, is facing an economic crisis on a scale not seen in a century. In April, its official unemployment rate ― that artificially low number ― was 27.2 per cent.

And the summer job season is supposed to be right around the corner.

Youth have been severed from the workforce like no one else. Their employment rate ― the percentage of people who have a job ― fell from 58.2 per cent in April of last year, to 38.2 per cent this year.

“According to the 2016 Census, more than half of the people in this age group were employed in sales and service jobs, which made up just under half of the jobs lost in March and April,” Caranci and Marple wrote.

“On the other end of the spectrum, very few young people are employed in management occupations, which shed very few jobs (2 per cent) over the past two months.”

While this age group makes up 14 per cent of Canada’s population, it made up nearly 30 per cent of job losses. And it’s not just part-time after-school jobs, either; this group lost 328,000 full-time jobs, which the TD economists describe as “literally off the charts.”

This could have an impact on this cohort for years to come, because “past recession cycles have shown that young people often bear long lasting scars on their livelihood,” Caranci and Marple wrote.

They cited a study of Canadian incomes from the 1980s and 1990s, showing that people who graduated into a recession suffered lower incomes than those who didn’t for up to a decade. The researchers estimated it would amount to 5 per cent less income over a lifetime.

A harder time at the start of your career means many things are delayed, including when you start saving for retirement or start building equity in a home. Raising a family also typically gets delayed, and “tragically, it has also been shown to have an impact on life expectancy itself, with increased mortality rates among people starting their careers in economic downturns,” the TD economists wrote.

Some observers worry that young people in particular will feel pressure to get back to work when the lockdowns are lifted, potentially making them more at risk in another outbreak.

“Low-wage workers are much more likely to work in occupations that can’t socially distance,” Macdonald wrote in his blog. “Without protective equipment and procedures, and the option to refuse unsafe work and remain eligible for CERB, those front line workers are at much higher risk of infection when they return.”

Employers and governments “need to be very careful that those who were hit hardest by initial job losses aren’t also hit hardest in a second wave of infection,” he added.

And what about the slightly older “young people,” the millennials? Their economic situation seems to be matching the national average ― they’ve lost about 15 per cent of all jobs in this crisis, a better record than Gen Z but worse than older generations.

But they’re facing one big problem: They are carrying an outsized share of this country’s household debt, including many of the largest mortgages, as a share of income. The risk of a debt crisis ― one that could spread to the broader economy ― “appears larger within this age group than in past economic cycles,” the TD economists wrote.

If there’s any good news here, it’s that “March and April data should prove the depth of the job losses,” they noted. But they urged governments to prepare “tactical measures” to help with the job market, “potentially well into next year.”

Women

The last recession ― the financial crisis of 2008-09 ― was sometimes dubbed a “he-cession” because of the outsized impact it had on men’s jobs. That economic downturn prompted many factories to shut down, and many others to automate, killing millions of relatively well-paid jobs for men worldwide.

This time around, we may be facing a “she-cession.” Women certainly took a disproportionate hit right out of the gate: In March, the first month of widespread lockdowns, women aged 25 and over lost nearly twice as many jobs as men in the same age group ― 403,000 fewer of them were employed at the end of the month, compared to a loss of 215,000 jobs among men.

That’s because women are over-represented in the (generally low-paid) industries that were shut down almost entirely in March ― bars and restaurants, hotels, beauty salons and air travel, among others.

Watch: Coronavirus pandemic worsens gender pay gap. Story continues below.

In the April jobs report, much of this gender gap disappeared. Sadly, it’s not because women got their jobs back, but because the layoffs shifted to industries dominated by men ― construction and manufacturing. The result is that April’s unemployment rate was 11.3 per cent for women, and 10.8 per cent for men ― not much of a difference, statistically.

That’s not the case in the U.S, though, where the “she-cession” was still evident in April. The U.S. jobless rate was 15.5 per cent for women, an all-time high, compared to 13 per cent for men.

The trend hasn’t gone unnoticed in Ottawa, where Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said his government will take into account specifically disadvantaged groups when helping with the recovery.

“What we’re seeing in these numbers is the reality on the ground,” Trudeau said at a press conference Friday. “People who are already vulnerable in the workforce, people who are already disadvantaged or facing extra barriers, are always the first to get hit when we have a difficult situation like this.”

Quebec

Every part of Canada has experienced a shock to the system from the COVID-19 pandemic, but nowhere more so than Quebec, which is contending not only with the largest viral outbreak in the country, but the sharpest contraction in jobs.

In the space of a few months, Quebec has gone from having the lowest unemployment rate it has ever recorded, to the highest ― 17 per cent in April.

That compares to a national average of 13 per cent. It’s also well above the jobless rate for the other part of the country dealing with a large outbreak, Ontario, whose jobless rate came in at 11.3 per cent.

So why is Quebec’s situation worse? For one thing, the province shut down its economy a little more than other places. While other provinces declared construction an essential service, Quebec shut its industry down.

The result? Quebec lost nearly 40 per cent of its construction jobs in April, double the nationwide average for the industry.

Many of those jobs may already be coming back. The province quickly reversed course on the construction ban, and allowed residential work to restart on April 20, with other construction sites starting a few weeks later. So those numbers could reverse themselves, to an extent, in May.

“The partial reopening of the economy, which began in late April in Quebec and, to a certain extent in Ontario, will bring people back to work,” wrote Joelle Noreau, senior economist at Caisse Desjardins.

Noreau noted many businesses are taking advantage of the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy, which covers up to 75 per cent of eligible wages, for up to 12 weeks.

“The situation will gradually turn itself around and, while the unemployment rate has skyrocketed, it will slowly come back down,” she wrote.

― With a file from The Canadian Press

You May Also Like

Escape Road: A Journey to Freedom

March 21, 2025

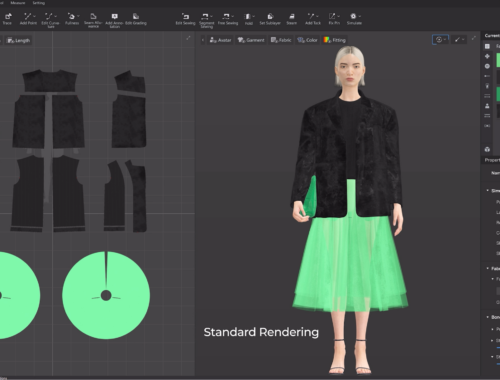

AI in Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining Design, Production, and Shopping Experiences

February 28, 2025