Bike Commuters Are Dying in Record Numbers

>

According to a report from the League of American Bicyclists released last month, 2016 went down in the record books as the deadliest year for U.S. cyclists since 1991. The report cites data from the U.S. Department of Transportation, which recorded 840 cycling fatalities in 2016—the first time the annual death toll has crept above the 1991 figure of 836.

That the United States has a problem keeping its cyclists safe is no surprise. A broader look at federal data reveals that the number of cyclists who die each year has hovered between 600 and 800 for the past several decades, with an average of 800 per year from 2006 to 2016. (The league’s report didn’t include data from 2017, when deaths dropped incrementally to 783.)

Across the country, mayors of big cities have declared ambitious efforts to put an end to biker and pedestrian deaths. Vision Zero initiatives have popped up in places like New York, Denver, Austin, and Los Angeles, and with them have come new bike lanes, bike-friendly road designs, increased signage, and other attempts to make roads safer for cyclists.

Clearly, though, it’s not enough to put a dent in the death tolls. As we reported last year, three years into its Vision Zero plan, Los Angeles saw a 5 percent increase in the number of cyclist and pedestrian deaths. Then there are the 840 people killed nationwide in 2016.

Jennifer Boldry, research director at People for Bikes, says we’re in the midst of a larger trend of increasing bike fatalities that stretches back a few years. “The bicyclist fatality rate [cyclists deaths divided by the total number of cyclists] is up an average of 2 percent a year over the past five years,” she says, despite the drop in deaths in 2017.

This is a measure not just of the number of people dying, but also of the number of people riding. According to Department of Transportation data, in 2006, 772 cyclists died and 623,039 people were bike commuting. (The U.S. Census tracks people who claim biking as their primary mode of transportation. The figure does not take into account people who ride for recreation, but it’s the closest that nonprofits like the League of American Bicyclists and People for Bikes can get to estimating how many bikers are on the road.) In 2012, 734 cyclists died and 864,883 people were bike commuting. In 2016, 840 cyclists died and 863,979 people primarily commuted via bike. Over the past decade, there’s been a roughly 6.4 percent increase in the number ofpeople bike commuting, according to American Community Survey data collected by Boldry; over the past five years, more cyclists have been killed.

Boldry points out that there are also more drivers on the road (DOT data shows higher numbers of registered vehicles and miles driven nationwide), thanks to relatively low gas prices, which could be a contributing factor to the increase in fatal accidents. She says other factors could be at play as well, like more people driving big cars while distracted by smartphones and increasing population density in major U.S. cities.Better bike lanes and bike-friendly infrastructure certainly helps with safety.“Despite increases in bicyclist and pedestrian fatalities nationwide, some states and cities experienced more people bicycling and walking—and fewer fatalities,” the league wrote in its report, citing the fact that Oregon has among the lowest bicyclist fatality rates in the country yet has seen a 46.5 percent increase in the number of people bike commuting over the past five years. “This suggests that bicyclist and pedestrian fatalities are not inevitable when people bike and walk more,” the report reads, “but may be reduced through proactive policy, infrastructure, education, and other community investments in bicycling and walking.”

But those changes have not been widespread enough to quell deaths nationwide. “We need to change our approach to designing roadways from ‘how do we move cars quickly’ to ‘how do we mitigate the dangers of our transportation systems,’” says KenMcLeod, policy director at the League of American Bicyclists.

In other words, nothing new and different is happening now that wasn’t already in motion five years ago. If anything, the numbers serve as a reminder that we have a long way to go to make cities safe for people on bikes.

You May Also Like

Automatic Weather Station Price Analysis and Market Trends

March 16, 2025

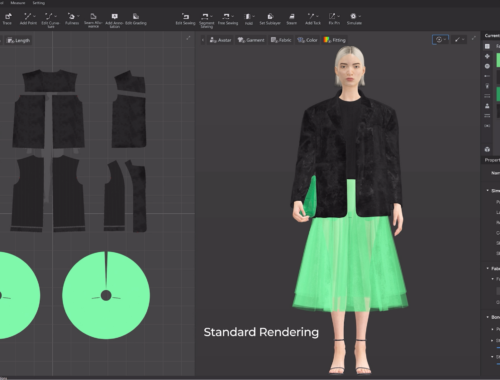

AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion

February 28, 2025