Are Vibrating Foam Rollers Worth It?

>

Last month, ultrarunner and endurance coach Ian Sharman completed what’s known as the Double Boston, running at an easier pace from the center of the city to the Boston Marathon start line in nearby Hopkinton before turning around to compete in the actual race. When he went home to Bend, Oregon, Sharman pulled out his high-end foam roller, the HyperIce Vyper 2, which contains a rechargeable battery to generate vibration, to help him recover.

Sharman has been using foam rollers for a decade to break up muscle tension and address sore spots, but for the past two years, he has joined a growing number of big names like Lindsey Vonn, Tom Brady, and Laird Hamilton in using the souped-up roller in his routine. Sharman says it mimics massage’s myofascial release—the breakdown of tight muscular tissue—but adds more power to the action. “It’s like a jackhammer breaking up the asphalt,” he says.

There was a lot of talk in the early 2000s about how whole-body vibration plates could lead to health and fitness gains. Some studies suggested it could stave off muscle soreness and keep you loose after a tough workout. There were even claims of rapid fat loss, muscle toning, and greater calorie burn. As a casual athlete, I distinctly remember trying one of the devices. The vibration ricocheted through my gut as I did a situp, producing an overwhelming urge to poop. Beyond that discomfort, these standing plates were also expensive and clunky, and they soon fell out of fashion.

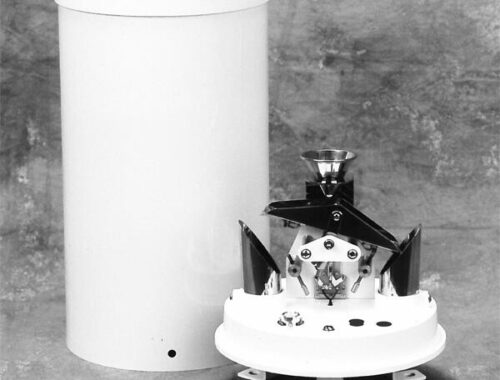

Today, interest in vibration is again on the rise as athletes see recovery as an essential part of their overall training regimen and have become more willing to invest in new products and techniques said to assist in that effort. One of the primary methods is targeted vibration and the multitude of smaller devices that provide it. Vonn has endorsed the HyperIce product range, which also includes a vibrating massage ball and a device that looks a bit like a power drill. TriggerPoint developed a vibrating version of its popular Grid roller. TheraGun says its handheld G2PRO is used by more than 100 pro sports teams (and has the sideline pictures to prove it). And TB12, fitness trendsetter Brady’s own line, recently created a roller and ball. The devices aren’t exactly cheap—costing between $100 and $600—but they are more accessible, convenient, and, many athletes would argue, more targeted than the heavy-duty gym-based vibration plates.

Proponents say smaller-scale vibration therapy zeroes in on trouble spots, aptly working to increase circulation, relax and loosen muscles, reduce pain, and improve range of motion. It can warm up the muscles before a workout and prevent soreness afterward, says Mark Coberley, associate athletics director for sports medicine at Iowa State University and a board member of the National Athletic Trainers’ Association. He uses steady vibration at a lower speed for relaxing muscles and at higher speeds to break down adhesions. “We have all kinds of rollers to help after tough workouts, but we probably use the vibrating ones most,” Coberley says.

The question is whether it works as a performance enhancer, a recovery booster, or both. The case for the therapy in general is that muscles respond to vibration by contracting and relaxing, says Lee Brown, a sports scientist at California State University, Fullerton. But up to now, most studies have looked at whole-body vibration, not the more directed type that these devices deliver. Brown says the vibration’s basic mechanism should be similar whether it’s deployed to the whole body or targeted to one muscle or body part at a time.

Looking at its potential impact before a workout, “the vibration sends signals to the muscle to contract, blood flow to the muscle increases, and it results in a warmer muscle,” Brown says. He, among other researchers, has found whole-body vibration to be similar to an active warmup—the kind you’d get with a light jog. Some studies have also shown increases in flexibility, power, and strength with this technique, says Nicole Dabbs, an associate professor of kinesiology at California State University, San Bernardino, but there’s not enough evidence to render it conclusive.

Then there’s recovery. Research here is still muddled as well, Dabbs says. A 2014 review found that it led to a slight decrease in muscle soreness, but a study just one year later, conducted by Dabbs and colleagues, found that the scientific support for most of the treatments (including vibration therapy) used to stave off exercise-induced muscle pain is “inconsistent and underwhelming.” However, a number of studies looking specifically at targeted vibration have yielded interesting findings as it relates to using vibration in hyperspecific scenarios. One study, for example, focused on downhill running and found that it helped runners recover more quickly.

As a whole, the current body of research, although still small, suggests that acute vibration therapy could possibly help with range of motion and blood flow, but not quite as much with recovery. In other words, there’s reason to believe that despite its promise, more research should be done to fully understand this treatment’s efficacy. In that vein, Dabbs prefers the phrase “potential performance tool” over “performance aid.” Vibration therapy isn’t likely to hurt you or your fitness, she says, but based on current evidence, you shouldn’t expect these tools to be a cure-all.

You May Also Like

コンテナハウスの魅力と活用方法

March 14, 2025

Sprunki: Unveiling the Mysteries of a Hidden World

March 20, 2025