Are the Leaders of the NPS, FWS, and BLM Illegitimate?

>

Before he took over as acting director of the National Park Service, P. Daniel Smith was best known for helping a billionaire chop down some trees on federal land. According to an internal report, Smith pressured NPS staffers to allow Washington Redskins owner Daniel Snyder to fell trees that blocked the river view of his Maryland estate in 2004. Nonetheless, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke could “think of no one better equipped to help lead our efforts to ensure that the National Park Service is on firm footing” when he handed the agency’s reins to Smith.

According to a complaint filed with the Interior Department in February, Smith’s appointment actually puts the NPS on shaky legal ground. The complaint was filed by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), a nonprofit watchdog group, and was addressed to the Interior Department’s deputy inspector general. Smith, the complaint argues, was illegitimately elevated to his position. And it’s not just him, says PEER—the same is true of the current leaders of the Bureau of Land Management and the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Per the complaint, the three acting directors were appointed in violation of the Federal Vacancies Reform Act, meaning every action taken by these men, PEER executive director Jeff Ruch writes, “is incurably void and invalid.”

Acting directors are meant to be placeholders in the absence of a Senate-confirmed pick, and the Vacancies Act gives a new administration 300 days to select a new leader. PEER’s complaint alleges that the Interior Department violated the Vacancies Act in two ways. First, the president alone can nominate acting directors. Yet Smith, the BLM’s Brian Steed, and Greg Sheehan, who was appointed acting director of Fish and Wildlife last June, were all appointed by Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke. Second, an acting director must have held a senior position in the department for 90 days during the past year prior to being appointed—another criteria all three lack.

President Donald Trump has shown little interest in nominating appointees, let alone their temporary replacements. Trump has yet to even advance a nominee for six of the 17 Interior Department positions that require a presidential appointment. (One such vacancy is the DOI’s inspector general, which is why PEER’s complaint was filed with the deputy inspector.) PEER’s argument is that if acting directors hold their positions in perpetuity, they essentially become directors appointed without congressional oversight.

“The question is whether or not these people who are running these agencies are subjected to any kind of public scrutiny,” Ruch says, “or is the Trump administration able to dig up anybody…without any public review or having to answer to anyone in a public forum, such as a Senate confirmation hearing?”

Interior Department press secretary Heather Swift wouldn’t elaborate on the department’s acting-director logic, saying only that the folks at PEER “are either lying or fail to understand basic facts.” In a February 23 response to PEER, the DOI’s Office of Inspector General said that “while these individuals have been referred to as ‘acting’ in various news reports and Department press releases all three of them have been formally given the title of Deputy Director.” (Rather than conducting its own formal review, the OIG referred PEER’s complaint to the Government Accountability Office.)

The simplest way the Interior Department could defend its action is to classify these leaders as “first assistants,” the top deputies who, per the Vacancies Act, are eligible to serve as acting directors without presidential nomination. If the DOI is making that case, however, it’s doing so in a confusing fashion. Swift has repeatedly said the men in PEER’s complaint aren’t serving in an acting capacity, but that notion is contradicted in the DOI’s own press releases and by a secretarial order that delegates the director’s authority to deputies. Another issue is that Sheehan’s and Smith’s deputy positions were created by Zinke and not Congress, which, according to University of California Berkeley law professor Anne Joseph O’Connell, “could raise both statutory and constitutional issues.”

“This is very fishy,” says Elaine Kamarck, director of the Brookings Institution’s Center for Effective Public Management. “The whole Trump government is walking on thin ice here. Continuing in this fashion makes all of their decisions vulnerable to court challenges.”

As of the beginning of the year, some 250 crucial jobs that required an appointee were unfilled across the government, many of which were being run by acting directors nearing their time limit under the Vacancies Act. This issue has been widely discussed, both in legal circles and among the media. As a reporter for NPR put it in an interview: “That law, the Federal Vacancies Reform Act, gives a new administration 300 days to fill posts, a deadline for Trump that has come and gone. So now if someone in an acting position makes an important decision, it’s subject to a court challenge as being improperly made.”

Or as the Vacancies Act puts it explicitly, “any attempt to perform the functions and duties of that office will have no force or effect.”

What it all amounts to, experts say, is a murky legal situation. And for those who believe Smith, Steed, or any other Interior Department acting director overstepped their authority, this only makes the case against them stronger.

You May Also Like

Essential Pool Supplies for a Perfect Swimming Experience

March 18, 2025

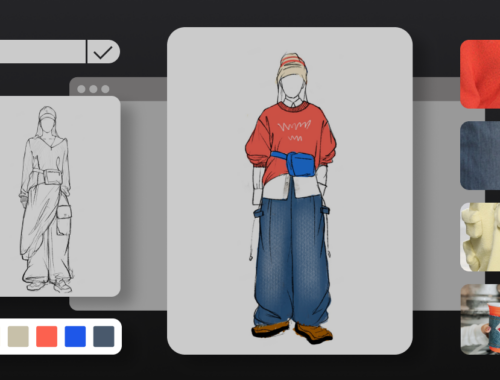

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025