American Kids Are Going on Strike for Climate Action

>

In early March, on the morning of her ninth-consecutive Friday striking from school, 12-year-old Denver seventh-grader Haven Coleman wakes up to look at her calendar and inventory her page-long list of the day’s tasks. “So I did like three e-mails, checked on my texts, and checked on Slack—that’s where the state leads are,” she explains. After touching base with a publicist and press adviser, Coleman and her mom head outto the Colorado state House, where she hunkers down for her three-hour climate strike on a bitterly windy day. Then it’s home again for another series of calls, e-mail, and tasks. Over 1,700 miles away, in New York City, 13-year-old seventh-graderAlexandria Villaseñor’s day takes a similar shape. She and her mom welcome NBC news into their apartment for a series of interviews. Later she sets up camp on her regular bench outside the United Nations headquarters. Then she goes home to wade through e-mail and fight climate-change-denying trolls on Twitter.

Coleman and Villaseñor are two of three coleaders directing the Youth Climate Strike in the United States, which is working to shut down schools across the country on March 15 to demand that world leaders act on preventing climate change. They say that some of their teachers are very supportive of their strikes, and some are not. But the good thing about skipping school is that, as middle schoolers working 40 hours a week leading a social movement, it’s kind of inconvenient to risk detention if you need to check your phone.

Villaseñor, Coleman, and a handful of other American studentshave ushered in 2019 by ditching class and going on strike every Friday, regardless of rain, sleet, or snow. The girls join tens of thousands of other young people worldwide who have been inspired by the outspoken 16-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. Thunberg has waged what has become known as her #FridaysForFuture strike outside the Swedish parliament building every Friday since September 2018, an effort to push all world leaders to sign onto the Paris climate agreement and limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial temperatures. Other countries that have seen student-led protests for the past few months include Uganda, Australia, Japan, Belgium, Germany, the UK, Spain, Canada, and Colombia.

“One of my demands is zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2030,” Villaseñor says, in addition to solidarity with Thunberg’s demands. Although each girl’s strike began this winter as an individual act, the actions have morphed into a strike movement led by Coleman, Villaseñor, and 16-year-old Isra Hirsi of Minneapolis.

The #FridaysForFuture movement, also known as #SchoolStrike4Climate, was slow to catch on in the United States. Kallan Benson, 14, of Maryland, and Zayne Cowie, nine, of New York, were the first to model strikes based on Thunberg’s, in early December. Villaseñor and Coleman got on board a few weeks later. However, it took more than two months before any of Villaseñor’s fellow students joined her on East 42nd Street, and Coleman had to learn to shrug off weird looks and haters who drove by and flipped her off. “It’s very frustrating,” Colemansays.“They don’t realize that… this will be the biggest problem of our generation. No matter what. Because we will be recovering from all of these droughts, heat waves, fires, snowstorms, tsunamis, sea-level rise.” And, she says, “We’ll have to work together.”

Coleman and Villaseñor, who met over social media but haven’t yet met in person, still show up every Friday at their respective protest locations, often alone, occasionally posting pictures of the two of them Photoshopped together in spite of miles of separation. Many of their classmates “still see themselves in the structure that we’ve all been taught to live in,” Villaseñor says. A few years back, at her old school, Coleman was bullied for trying to educate her classmates on climate breakdown. Although Villaseñor, Coleman, and Hirsi all note a degree of apathy among fellow students, as soon as they teamed up and went public across social media with plans for the March 15 strike, the trio immediately heard back from student leaders across the country who also wanted to lead state-level strikes. Such events are now planned in more than 80 U.S. cities and 92 countries, with an expected turnout of 100,000 nationally. Hirsi and Coleman estimate that they’re spending between six and eight hours each day answering e-mail and fielding calls with reporters and other students. “I don’t have any extracurricular activities,” Coleman says. “Climate is my extracurricular.”

Hirsi agrees. Though she has organized a handful of school walkouts and actions urging local lawmakers to pass a Green New Deal for Minnesota, this is the first time she’s organized anything at the national level. One of her main jobs is managing student leaders in each state—many of whom are older than she is. “It feels really stressful, because I’m only a sophomore,” Hirsi says. “My family says that I’m taking on too much, that I should dial it down a few notches. I can’t. I say I’ll try, and then I schedule more calls and meetings.”

But at the end of the day, they’re still adolescents. “Sometimes I just feel so screwed over by this,” Coleman says. “Like, sometimes I’ll just sit and cry for like an hour about just how terrible this is.”

The pressure of the work beats standing still. Villaseñor, who is originally from Davis, California, was an hour from the Paradise fire when it broke out this summer. “It was very postapocalyptic,” she recalls. Other young activists throughout the world, who have also been striking on Fridays since January, or earlier, echo this sentiment. Lilly Platt of Holland is horrified that the ocean will soon be filled with more plastic than fish, Holly Gillibrand of Scotland is concerned about the lack of biodiversity on grouse moors, and Vanessa Nakate of Uganda is troubled by seeing drought in January, which is traditionally the rainy season.

Choosing to self-educate and to act has not been all worry and sacrifice. After all, these young people have found each other and have become, as Coleman calls it, her ever growing international “climate family.” “With all the darkness we face now, you gotta find the joy,” she says. “It’s helped me be even more positive. And that’s helped me push through the bullying and the remarks on social media. I’m finding the little joys that we might not have in the future, and I’m cherishing them: A plant in our room. All the animals that future generations won’t be able to see… only in picture books.”

You May Also Like

AWS Weather Station: Monitoring Environmental Conditions with Precision

March 17, 2025

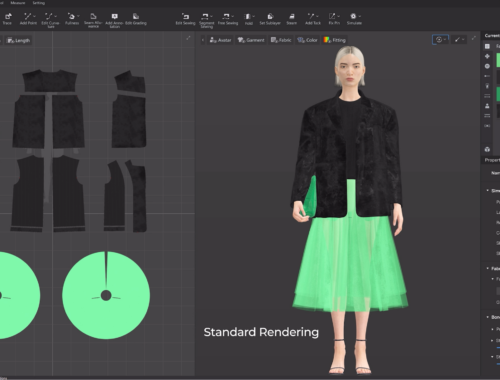

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Supply Chains

February 28, 2025