Alexi Pappas Takes Napping Seriously

The Olympian and filmmaker on mastering work-life balance—a skill she learned the hard way

As a professional runner, I’ve learned that balance is key to successful training. Sleep and recovery are just as important as hard workouts, and I’ve grown to take my nap time as seriously as I take my runs. I’ve even started calling my daily naps my “second practice” for the sake of explaining it to other people. (It’s much easier to schedule a meeting around “practice” than around “my nap time.”)

I try to apply that same philosophy of balance to my overall lifestyle. We can’t be on the job 24 hours a day—whether that job is running or something else entirely.

But balance is a funny thing, because sometimes the best way to improve it is by losing it. I found that in my pursuit of a balanced life, I sometimes swung too far in the opposite direction. When I was preparing to shoot my movie Tracktown, I tried my very best to balance full days of intensive training with equally full days of writing and preproduction work. A ringing phone would interrupt a post-training nap, a pressing deadline would conflict with a workout, or I’d stay up late writing and feel exhausted for my morning run. It started to feel like I had overextended myself and that I was failing as both an athlete and a filmmaker.

The first thing I learned about balance is that it’s very mental—the feeling of two activities being compatible (or not) can be more powerful than the actual time or physical demands of the activities themselves. Once I started feeling like my running and my filmmaking were in direct competition with one another, nothing I did ever felt good enough. There weren’t enough hours in the day; when I was running, I felt like I was neglecting my other commitments, and vice versa. As a result, my performance in both pursuits suffered—I felt permanently stressed and distracted.

But I knew I couldn’t give up—making it to the Rio Olympics and finishing my movie were too important to me. So I accepted that balance often requires teamwork. Getting help is okay. This means forming a team that’s on board with the musts and optimistic about the opportunities in between. For instance, my partner Jeremy is incredibly flexible—if one of us had to stay up all night working on Tracktown, it was him. He always let me eat my post-workout protein mush next to him as we edited scenes from the film, despite the risk of spillage. My coach also understood how important Tracktown was to me, so he didn’t schedule any ultra-intense workouts for the few days when I had to travel down to Los Angeles for the film’s premiere. Even though the timing wasn’t always ideal from a purely athletic standpoint, we felt good about our plan because we knew the positive energy I would feel from avoiding workout anxiety during the trip would be best for my training in the long run.

This sense of teamwork felt synergistic and positive: Jeremy, my coach Ian, and I were all contributing toward our shared goals. Between the three of us, we would finish Tracktown and we would make it to the Olympics.

Once I began to proactively balance my life by enlisting the support of my closest people and making sure we were all on the same page about the big-picture goals, everything clicked into place. Rather than feeling like my different pursuits were in conflict with one another, they felt like they fueled each other: I’d run feeling happy about the progress we were making on the movie, and I’d carry that positivity about my fitness into meetings and writing sessions. It’s a deliberate choice to focus on how our different commitments enhance each other, rather than dwell on how they might detract from each other. Having a consciously optimistic outlook is key.

Of course, there are practical and tangible limits to balance. As an athlete, it’s okay to skip a nap now and then, but it’s not okay to skip my nap every day. As a filmmaker, it’s okay to sit out of a few meetings, but it’s not okay to miss an important call with an investor. Balance is about knowing what can give and what can’t and making sure you understand your red lines.

Flexibility and reevaluation are also important to maintaining healthy balance. During high school and college, for example, I would adjust my social calendar for certain times of the year: During the competitive season, I lived like a hermit with my teammates, but after the season ended, I made sure to come out of my shell and hang out with my nonathlete friends, go to parties, and get involved in other activities outside the team. Runners often behave like we’re perpetually in competition—it’s important to let go of that mindset and take breaks when the time is right.

Taking breaks and pursuing other interests is a net positive: When we’re happier and well-rounded, we tend to perform better. Maybe some athletes don’t function this way, but I know from personal experience—and from observing many other elite athletes over my years in the sport—that living in a constant state of razor focus can lead to unhappiness, injury, and burnout.

For a long time, when I started seriously working on making my movie, I could sense skepticism, and even cynicism, from some of the people around me—competitors, journalists, and even coaches. I felt embarrassed to be pursuing this nonathletic interest, and that negativity contributed to my stress and exhaustion. But then I realized that as long as I could show up on the start line and perform, it didn’t matter what anyone said or thought. I knew my performance on the track would speak for itself, and it did. This has become my approach as an artist and athlete: My accomplishments in each pursuit must stand on their own. While many people see me as an “athlete-artist,” I see myself as an athlete and an artist. My stress gave way to a newfound sense of empowerment and confidence, and now I’m a stronger athlete and happier person because of it.

You May Also Like

Pool Products: Essential Accessories for Your Swimming Pool

March 17, 2025

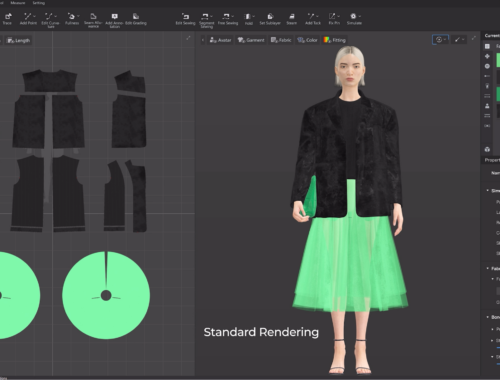

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025