Aidan Haley on How to Become an Adventure Filmmaker

The Boulderite went from knocking on doors in Paris to editing a feature film

Aidan Haley still remembers the night in May 2001 when he realized he wasn’t destined to be a professional alpinist like his cousin Colin Haley.

“The two of us were bivied in a tent under the northwest face of Mount Stuart in the Cascade Range at about 8,000 feet,” he says. “It’s one of the most exposed pieces of granite in the lower 48. We were going to climb the Mount Stuart Couloir the next morning, and I was pretty anxious.” Aidan shook Colin awake and confessed he wanted to bail. “Then I asked whether he ever got scared before a climb,” says Haley. “There was this long silence, and finally he was like, ‘No, dude. Never.’ It was just this complete lack of comprehension.”

On the couloir the next day, Aidan took a few photos of Colin. “I thought, ‘Oh, wow, this is pretty cool, too. Maybe I could do this as my career.’” Fifteen years later, Haley’s films and edits have been chosen as finalists at Banff Mountain Film Festival, Telluride Mountainfilm, and 5Point Film Festival, and his clients include The North Face, Patagonia, National Geographic, Outdoor Research, the National Park Service, and REI. Most recently, he worked on Krystle Wright’s Where the Wild Things Play.

Age: 30

Job: Filmmaker

Hometown: Tacoma, Washington

Home Base: Boulder, Colorado

Morning Ritual: “Every morning, I take a moment to enjoy the beginning of the day before I jump into work. Usually with coffee.”

His Favorite Gear: “I edit on my MacBook Pro using Adobe Premier. Fancy technology will make your job possible, but it won’t make you a better editor. You have to be able to make do with whatever tool you’re given.”

Who He Looks Up To: Ben Knight, Krystle Wright, and Ben Sturgulewski

Career Highlight: “Growing up, I’d come home from school and watch Matchstick Productions’ ski films; I idolized them. This past summer, I spent two months in Alaska editing a film for them.”

How He Made It: “I started out as a photographer. I only took one relevant class during undergrad, but I got my first internship right out of college at an agency in Paris—I knocked on their door. Everybody says that nothing will be handed to you in life, and that’s true—especially professionally. If you want the job, go introduce yourself.

“I started diversifying my skill set around 2008, because tons of accessible digital cameras started coming out and threw photojournalism into a monumental shift toward video. I moved to Los Angeles and learned a ton as a commercial director’s assistant, but eventually I joined an outdoor media company in Seattle, because I wanted to combine adventure sports and filmmaking. I built up my contacts for a few years, and then set out on my own. At every juncture, I put myself in positions where I’d learn a lot; in this industry, it’s so important to have a broad range of skills.”

On Making It Without Credentials: “I never went to film school, but I only taught myself maybe half of my skills—I surrounded myself with people who knew a ton about filmmaking, listened to what they told me, and worked my butt off. If you want to make movies, I don’t think film school is the ideal route. You gotta be out in the field to get true experience; it’s the difference between talking about making shit and actually making shit. When you start out, your work probably won’t be any good, but over time it’ll get better and better.”

Jumping Hurdles: “When I started freelancing, I was terrified about not having a steady paycheck or structured schedule. You have to push through and embrace those insecure aspects. Think of it like this: A lack of structure is actually freedom—it means you can work on different types of projects. I do general commercial work, not just adventure films, and I’m wrapping my first feature film. If you stay nine-to-five, you’ll only have a few hours each day to work on passion projects; that’s hard to manage. Don’t get me wrong, freelancing is tough, especially at first. Building connections, a portfolio, a name—those take time.”

Workspace Setup: “I work from home, but this coming year I’ll probably be working in a shared creative space with some other people. Being stagnant is a crutch, and hearing others perspectives will open your eyes.”

How to Schedule Playtime: “My advice is to do whatever it takes to finish an assignment well and on time, and also schedule big chunks of vacation between projects. For instance, I’m going on a surf trip to Indonesia pretty soon, but I won’t be talking to anybody about work while I’m there. You have to take gaps to feed your soul. I enjoy editing and creating, but no matter how much you like your job, you gotta recharge. When I’m not on vacation, I still take breaks to go trail running and climbing.”

What People Don’t Realize: “My peers with nine-to-five jobs often think I don’t work very much or very hard, which is completely wrong. Often, my job is nine-to-nine. If you want to be a freelance filmmaker, think about the last time you worked 24 hours straight, then imagine doing that for an entire month. Growing up, I took a lot of shortcuts on my homework—you can’t do that and be any good at filmmaking. Editing is a meticulous job, so if you screw up one tiny step at the end of a five-hour process, you gotta go back and repeat the whole thing again.”

Not Letting Your Career Become Your Identity: “I let my work dictate my life when I was younger, and now I try to consciously separate myself from my job. Don’t get me wrong—I love being a filmmaker, and I don’t see this ride ending anytime soon—but there are hurdles in every career, and you have to keep your eyes open. I may get burned out, or eventually I may not be able to find consistent work. The only consistent thing in life is change, and you have to be ready to reinvent yourself in case things don’t work out. That’s tough to do if your career is your sole identity.”

Owning Your Work: “I shoot occasionally, but I’m mainly an editor—that means I have to work on other people’s projects. But there’s a difference between someone seeking you out because they want you, specifically, to edit for them, compared to having to search for work yourself. In the latter case, you’re working for someone, not with them. Editing is a huge time suck, you know? It’s important to feel a sense of ownership—you are your hours. This past weekend, I literally spent three days straight in front of my computer; it was draining, but I was inspired because I felt in control. When you collaborate with a great team, work feels less like a job and more like a craft. Of course, it’s nice to choose your own off-hours: Right now, I’m sitting on a beach with my surfboard, getting ready to go paddle out and spend the day in the ocean.”

Staying Creative: “It’s all about diversity. If you work on different types of projects, your mind will stay flexible and sharp. When you’re first starting out, that’s easy to do: You have to keep learning different techniques and fresh ways to tell various types of stories. Farther along, I think working with creative people is what’s most helpful for coming up with new, interesting ideas. The outdoor industry isn’t really into team sports, but that’s what filmmaking is like—it works best when it’s collaborative.”

What’s Next: “I recently shot my first feature film, and now I’m editing it. It’s called Nona. Michael Polish directed it, and Kate Bosworth produced and stars in it. It’s been a blessing to be a part of. This fall, I’ll be working on a branded video for The North Face about trail running. To be honest, I’m always excited about my next project, but I try not to get caught up in what might happen way down the road. Deal with what’s in front of you, and the rest will take care of itself.”

You May Also Like

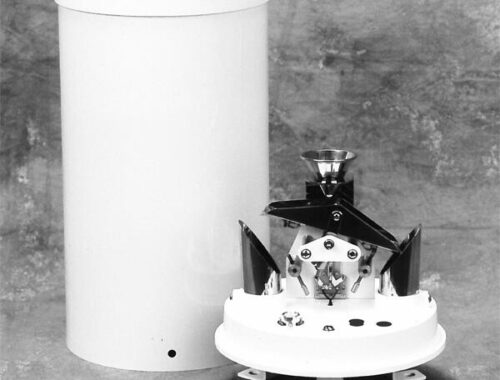

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025

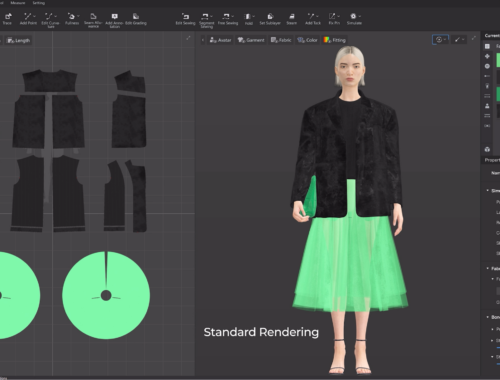

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025