Actually, the Mega Season Pass Is Killing Skiing

>

Starting next winter, Vail Resorts’ Epic Pass ($939) gets you access to 67 resorts. Alterra’s Ikon Pass, just $10 more, is good for unlimited days at 14 North American resorts. The season pass is truly having a heyday.

Recently, Marc Peruzzi argued in Outside that this massive consolidation occuring across the ski industry is a great thing for core skiers. His argument was essentially that skiing, overall, is getting cheaper.

OK, sure. But the cost issue is a lot more complicated when you dig into it. The relatively cheap passes that result from the industry’s consolidation are a great deal—if they existed in a vacuum. But they don’t.

Vail Resorts is a publicly traded company with a current market capitalization hovering near $8 billion. Alterra is a privately owned entity reportedly worth around $4 billion. Why aren’t core skiers, the people who live in ski towns, happy that gigantic business interests seem suddenly aligned with their own?

To start, these companies grew as large as they did by acquiring other resorts, a trend that began in the 1980s. That development, as Peruzzi rightly notes, has led to homogenized ski areas and coddled, tepid so-called “experiences” for weak skiers with strong wallets. There is certainly more to the story than these easy targets.

In the wake of Vail’s 2017 acquisition of Stowe, in Vermont, real estate prices, which weren’t cheap before, rose notably, according to Gayle Oberg of the locally based Little River Realty. “There’s been a significant difference. Prices are as high as we’ve seen,” says Oberg, who originally moved to Stowe to ski bum in 1973. Big Sky, Montana, was recently added to the Ikon Pass network, and already locals are feeling the housing squeeze. “All the affordable long-term rentals we had before this year are now off the market and seem to be on VRBO,” said a longtime local and resort employee, who requested anonymity for fear of losing their job. “It’s priced out all the people that support this town. I know of resort employees living in tents in the forest. People here are really pissed off.” One could blame global market forces and nationwide shortages for housing crunches (and they would not be totally wrong), but massive pass systems bringing large swarms of people to small mountain towns certainly don’t help.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that any ski corporation has a duty as a fairy godmother to ski culture, soul skiers, or the surrounding communities. Vail’s duty is a fiduciary one—to its shareholders. Alterra also has investors. They aren’t responsible for anyone’s ski dreams. But, while Peruzzi may tell us they are “throwing [core skiers] a lifeline,” they’re certainly not doing that either.

For about seven years, residents of Squaw Valley, California—core skiers if there ever were any—have worked to oppose a huge development proposal at the base of Squaw by KSL Capital, a founding partner of Alterra. They fear thousands of more tourists, heavier traffic, high-rise hotels, a lower quality of life, and significant environmental impacts. According to Squaw icon Robb Gaffney, locals raised half a million dollars to support the incorporation of Olympic Valley, the community in Placer County that houses Squaw. As a municipality, they could deny the project. “Everyone donated, even waitresses throwing in $20. And we were just bulldozed over,” he said. “KSL spent nearly a million dollars to thwart a democratic process through legal maneuvers. It’s really different when you’re facing a multibillion-dollar company. Even though there is huge local opposition, there is an agenda and a high-powered legal battle to take [the development] to the finish line.” Alterra’s president, David Perry, said in an e-mail that while his company supports each resort “having significant local decision making and keeping the resort and community working together as best they can,” the situation at Squaw is “a different topic with its own complexities.” A cheaper season pass seems like small consolation for giving up control of your community.

For the industry, perhaps the biggest casualty of the mega pass has been the single-day lift ticket. A day pass at Vail recently hit $209. Compare that to a day pass at some world-class mountains in Norway ($55), Argentina ($40), Switzerland ($70), or Japan ($50). At the same time, average accommodation prices at western U.S. resorts have risen 30 percent in the last eight years. It’s no wonder that annual U.S. skier days have dipped over the last 20 years.

“The U.S. ski industry is facing… increasing prices, paid by a declining number of customers,” analysts wrote in the 2018 International Report on Snow and Mountain Tourism. “This tends to make ski[ing] less affordable… especially for the beginners, who usually purchase daily passes…. The business model of the large U.S. resorts [can be summarized as trying to get] always more money from always less customers.”

Vail Resorts has long been the butt of skier’s jokes, for its expensive, bland, and commercial reputation. Peruzzi cheerily writes that “with shareholders calm, the company can invest in better grooming, new lifts and restaurants, and staffing.” Staffing, you say? In a telling anecdote from just three seasons ago, Vail reportedly tried involuntarily cramming 100 more beds into its Keystone employee housing. The plan was to add two more residents per select two- and three-bedroom units, increasing the occupancy of those to four- and five-person units, respectively, creating a college-dorm-like situation. The company later tried to sell these as a voluntary program that offered employees “financial incentives”—employees were to be charged $330 each in the increased-occupancy rooms, instead of $460. However, if you do the math, the total rent for each unit would actually increase by $270 for a three-bedroom unit and $400 for a two-bedroom unit. Maybe you think saving $130 on rent is a good thing (and worth taking on a roommate for). I disagree. So did the staff, which had a fit until the resort quickly backpedaled.

Vail quietly got what it wanted six months later by pressuring the county to allow the “temporary” employee density, which it then tried to extend in September 2018. Luckily, county commissioners rejected that request. The company has also made a point of publicizing its $30 million pledge for employee housing, made in 2015. However, whether the company has upheld that pledge has come into question.

And anyway, $30 million doesn’t actually equate to much when it’s spread across the company’s wide portfolio of resorts. Vail Resorts actually denied a county request to split a $300,000 cost that would bolster the company’s chances of receiving approval to include low-income rentals in its new employee-housing development in Keystone (meant to alleviate some of the housing issues that contributed to the aforementioned controversy), leaving the taxpayers on the line. Meanwhile, Vail just announced an approximate $180 million commitment to “reimagine the guest experience” by upgrading lifts, on-mountain dining, and other superimportant stuff. Peruzzi’s implication that the company cares about investing in its staff—writing that “the big companies have brought better jobs”—is laughable. Those better jobs are in Broomfield, not Breckenridge, and the money from your mega pass is padding the pockets of executives, not the average worker, who deserves to be treated fairly.

Ultimately, we could worry that these big passes are in fact the death knell of affordable skiing. But independent ski areas do still exist—for now. And skiers and riders can still support them with their wallets. At these ski areas, there may still be bars at the base that haven’t been converted to genteel, pricey après bistros and are fun and rowdy enough to actually sell you the cheap PBR that Peruzzi suggests season pass holders can buy with their extra money.

You May Also Like

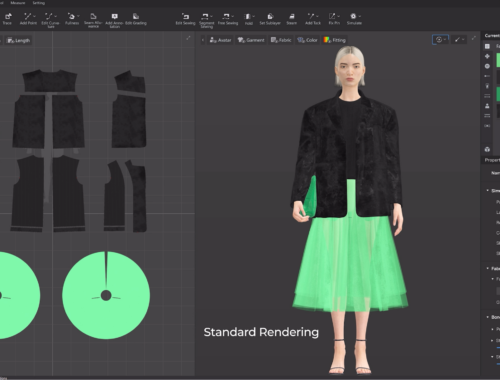

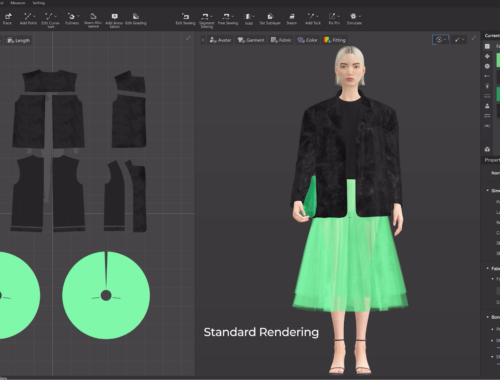

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for a Smarter Future

February 28, 2025

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Sustainability, and Shopping Experiences

February 28, 2025