A History of Marathon Fueling

What was once spontaneous consumption has turned into a science of its own

Today, marathon nutrition is a closely dialed science. Runners prepare their bodies to eat and drink during the race the same way they train to run it.

It wasn’t always like this. A century ago, runners didn’t map out when it was time to pop that fifth gel, and running stores weren’t flush with blocks, beans, and chews promising to prevent the dreaded bonk. Back then, midrace brandy swigs and aid-stationless courses were the norm. How far have we come? We talked to marathon history experts, running enthusiasts, and modern-day racers to find out.

Boozy Runs Are the Best Runs

At the turn of the 20th century, marathoning looked much different than it does today. In the 1897 Boston Marathon, the race’s inaugural event, only 15 men competed, compared to the nearly 15,000 men who ran this year. (Women weren’t even allowed to run it until 1972.) Modern aid stations—long tables of Gatorade and water and sponsor booths passing out gels, chews, or candy—didn’t exist. Instead, each runner had handlers: people on bikes or in cars somewhere along the course ready to provide nourishment.

Fueling typically meant a shot of whiskey, brandy, or other alcohol. Spyridon Louis, winner of the marathon at the 1896 Olympics, sipped cognac with fewer than six miles remaining. The 1924 Paris Marathon featured a fluid station offering pours of wine to runners.

Midrace hydration wasn’t scientifically understood, and anything other than the hard stuff while running was frowned upon by those who governed the sport. “There was some sort of machismo ethos in running, where it was a sign of weakness to drink water when you were thirsty during exercise,” says Matt Fitzgerald, a certified sports nutritionist, author, and California-based running coach. “So people would try not to.” Race organizers would discourage it as well: During the 1904 Olympic Games in St. Louis, only two water stations were available, the second of which appeared right after the halfway mark.

Looking back, “it was a terrible idea,” says Tom Derderian, longtime coach at the Greater Boston Track Club and author of Boston Marathon: The History of the World’s Premier Running Event.

The Sports-Drink Revolution

According to Tim Noakes’ book Waterlogged, it wasn’t until the 1960s that the importance of staying hydrated while covering long distances began to take hold among the running community. And even then, it wasn’t until the mid-1970s that thoughtful hydration became common practice. Although runners and race directors sidelined the booze, they still had no real concept of how to stay adequately hydrated and maintain energy levels during a race. A lack of easy-to-transport and nutrient-dense products meant that runners turned to things like oranges, salt, and decarbonated soda for fueling. They’d drink when thirsty, but not much more or less.

“It was spontaneous,” Derderian says. “ Whenever you had something available to drink, you did. Your only goal was to make sure that whatever drink you chose didn’t require a lot of digestion.”

The first major change came with the invention of Gatorade in 1965 by a team of scientists at the University of Florida School of Medicine. This new carbohydrate-electrolyte drink debuted on the football field and made its way to mainstream running after several clinical trials with distance runners. For the first time, athletes could game their hydration in a way that would prevent thirst and restore sugar and electrolytes without having to eat something.

It’s Not Just About the Liquids

In 1983, Brian Maxwell, a Canadian Olympic marathoner who at one point ranked third in the world, bonked hard in a race and blamed the crash on low blood sugar. He began a grassroots campaign to build a product—known as PowerBar—and get it into the hands of endurance athletes, mostly ultramarathoners at first. The bar became a household name by the end of the decade.

As races became more competitive and elite runners ratcheted up their PR efforts, stopping to unwrap a bar or unpeel a banana became precious time wasted. Gu, founded in 1994, sought to provide concentrated energy in a gel so athletes could easily replenish energy without stopping.

Now runners will tape the gels to their fuel belts, around water bottles, or find other ways to have them readily available to eat and move along quickly. It’s rare to see anyone running with whole foods during a 26.2-mile race because of their inconvenience and the toll that eating such foods while moving could take on your body.

Most sports nutritionists recommend runners take in about 60 grams of carbohydrates per hour during a marathon. But “the human body was not meant to absorb nutrition during running,” Fitzgerald says. “It’s not too surprising that the things that tend to work best under these conditions are not natural foods, since you are doing something that’s unnatural to begin with. The normal rules of healthy eating are just flipped on their head as soon as you start running. You are not eating for health or longevity; you’re eating for performance.”

Fueling Gets Individualized

For months leading up to Nike’s Breaking2 Project in May, Nike scientists and experts exhaustively studied its runners to see how they could extract peak performance from the human body at will. When Eliud Kipchoge ran a 2:00:25, he set in motion the trend toward highly individualized race fueling across all levels of runners, Brian Vaughan, CEO of Gu, says. Gu and other companies have started to field teams of scientists to figure out sports nutrition for the individual, with the goal of making such information available to both elites and amateurs. Companies like InsideTracker (although still contested for a lack of scientific certainty around its findings) analyze blood samples and claim to create specific training and nutrition plans for a given individual based on that data.

“Sports nutrition in the last decade has exploded,” says Magda Boulet, vice president of innovation, research, and development at Gu and second-place finisher at the 2017 Western States 100-mile race. “There is so much effort into researching. I think we’ve been so focused on just optimizing the race-day performance. But we are so much smarter now, and we are looking at how sports nutrition can optimize your training as a whole.”

You May Also Like

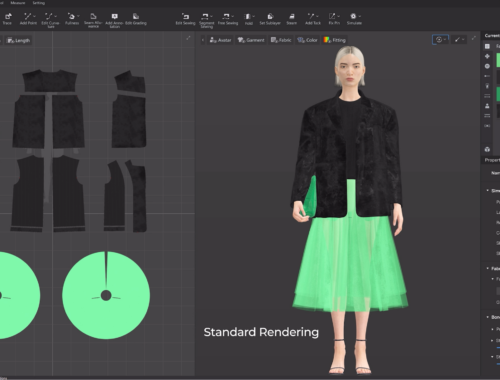

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Supply Chains

February 28, 2025

Google Snake Game: A Classic Arcade Experience

March 23, 2025