A Beginner's Guide to Dating a Birder

>

Hiking with Jessie, my significant other, means flushing birds by pishing so we can look at their jizz. I learned what this means the old-fashioned way in 2012, without Google, on our first hike together. It means moving very slowly.

I am not a birder, though I’ve learned a lot since dating one. At the University of New Mexico, Jessie researches, writes, and reads about birds. She even writes about researching and reading about birds. Those who surround her also watch birds, and they in turn surround me, throwing around lingo I don’t understand. “I can only contribute the occasional ‘I saw a bird once,’” Vince Ortega, a nonbirding fiancée of Jessie’s former lab mate, once told me in solidarity.

My greatest birding accomplishment remains spotting a pack of endemic fowl crashing through underbrush in Borneo, making loud, chicken-like noises. I spotted them because I didn’t have binoculars and was limited to looking only at the ground. Jessie gave me a pat on the back and said, “Good boyfriend.” Then she went back to looking at them. I was thrilled.

Such victories come sparingly when every bird soaring above you looks like a raven. When you’re in love with a birder, it’s usually best to just stand back and watch them.

I do this mostly by tagging along with Jessie’s lab in the field—or at a bar where they gather after their lab meeting on Fridays. It’s a strange scene at 5 p.m., a nerdy collection of biologists ordering IPAs at a fratty bar with sticky floors. Birdwatchers frequently find tranquility in places many consider unsavory—remote desert puddles, drainage ditches, or garbage piles—where they see attractive habitats for themselves and avifauna. Here, at dusk before hoards of patrons arrive, we have a balcony overlooking the Sandias all to ourselves. You can gaze across the valley for wildlife—merlins, lesser goldfinches, and Cooper’s hawks that dive-bomb packs of clumsy, idiotic doves.

These identifications thrill birdwatchers, and they have taxonomies for fellow birders as well. Once, after taking a professor’s recruiting call when she was applying to grad school, Jessie made an observation that confused me.

“I’m so glad he’s a birder,” she said

“Aren’t all ornithologists birders?” I asked.

Dumb question. Jessie explained that, for some ornithologists, a bird is merely a vessel by which to study more exciting aspects of evolution, ecology, or conservation. Such ornithologists were a mystifying subspecies; they would finish a day of fieldwork outdoors, often in exotic locations, and then not return to look at the birds for fun. The horror. I was lucky not to be dating one of those people.

So who are the ideal birding companions? They are, I’ve found, often old and retired. Madi Baumann, who’s married to Matt, a savant of New Mexico birds in his early thirties, verified as much. “Something that took some getting used to was how many random phone calls he would get from older men that I knew nothing about.” They turned out to be innocent birders calling Matt to report sightings, plan trips, or get tips. But they were also unexpectedly useful assets—bullpen relief for nonbirding partners wishing to sleep later than 5 a.m. Other birders claim conversion is inevitable. On one trip, Jessie and I met a couple from Texas. Only the groom was a birder when they married; five years later, the bride had taken up birding and renounced Christianity for atheism. She said the two events were related.

When dating a birder, everything—from religious beliefs to daily habits—is affected by avifauna. Jessie refers to children as “offspring.” Homes become “nests.” Noteworthy hair becomes “plumage.” A few weeks ago, lounging on the couch, Jessie said she was roosting. On another occasion, she showed me videos of colorful birds doing bizarre, elaborate mating dances—one male in front of a creative lean-to he had built worthy of Andy Goldsworthy, decorated with purple flower petals. I looked around the house and then at myself, pasty and unremarkable, and pondered my underwhelming bank account as a freelance journalist. I wasn’t sure what Jessie was trying to suggest.

She is more straightforward, however, when relieving me of driving duties after I fail to stop for birds. Once, while leaving New Mexico’s remote Gila Wilderness in our 1997 Honda CRV with nearly 300,000 miles on it, Jessie spotted some birds and took the wheel—suddenly unworried about the engine overheating. She looked everywhere but the road, screeching to sudden halts when something fluttered nearby, while I improvised prayers in the seat. “I honestly don’t know how they stay on the road,” says Aaron Matins, a nonbirder dating Selina Bauernfeind, one of Jessie’s lab mates.

Birding by foot tends to be more relaxing. A few years ago in Thailand, I brought a Kindle along on hikes and strapped a foldout chair to my pack. When Jessie came upon mixed flocks (a group of birds with many species, which is very exciting), I’d settle in and get some reading done. Hiking loops work wonders; on that trip, I completed an eight-mile circle and linked up with Jessie after she’d gone less than one and a half. She had barely noticed my absence.

I hung back for a bit, lovesick and even a little envious, watching Jessie stumble onto gold mines of her own fascinations. She’d just moved to Beijing with me, and Thailand marked her first time birding in Old World tropics. Their canopies concealed thousands of unopened gifts; watching her find them, I sometimes felt disappointed a similar curiosity didn’t grab me the same way.

Increasingly, I find myself in awe of great birders—their recognition of songs and calls and the seemingly invisible details they use to identify the LBJs—the “little brown jobs” of drab gray and brown birds that all look the same. They value something intimate about the natural world in a way, I suspect, that even the most stoked outdoor enthusiasts can’t. Lately, I’ve found myself ditching the foldout chair for binoculars, and I’ve gotten better at making IDs. Last summer, I spotted Jessie her first pair of American three-toed woodpeckers, this time slightly off the ground on a log—a small improvement from the fowl I’d spotted in Borneo. And in April, according to the birding site eBird, I recorded the third black-chinned hummingbird to arrive in Albuquerque, a feat I proudly recounted at lab drinks.

A few weeks later, Jessie and I were driving back from a weekend of camping with her lab in Boone’s Draw, a sweltering ditch of forest patch in the eastern New Mexico desert that attracts desperate migrating birds. Aaron was driving, Selina in the passenger’s seat, and I sat next to Jessie in the back, napping and guzzling Gatorade to recover from near heatstroke. As we approached the Sandias, Aaron remarked that a recent hike with Selina had gone slower than expected, and I offered my condolences—six years of them now. Selina and Jessie laughed, but neither promised change. We weren’t hoping for it anyway.

You May Also Like

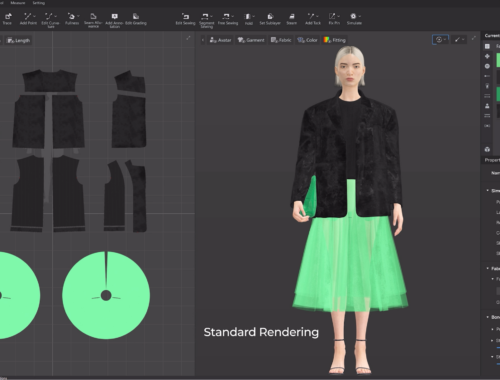

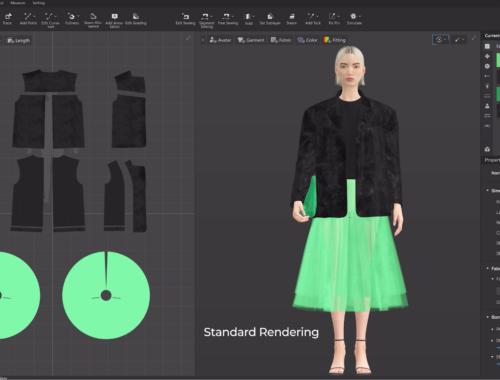

**AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability**

February 28, 2025

Generated Blog Post Title

March 1, 2025