Changing America, part V: The coming millennial boom

In the weeks before residents of Tulsa, Okla., went to the polls last spring, coasters started showing up in the city’s bars advertising a party outside the county elections office. The group of civic-minded young professionals who paid for the coasters offered free Uber rides to the party, where people could vote early. They ordered pizzas and set out yard games. They paid for buses to truck in high school seniors, eligible to vote for the first time. In April, voters approved a bond measure raising taxes to fund economic development with more than 70 percent of the vote. In June, the incumbent mayor lost his bid for reelection to a younger city council member who promised a more livable city. In both elections, turnout among voters under age 40 soared by 50 percent. “Getting new voters to show up is really the ultimate metric,” said Daniel Regan, who headed the young professionals group that paid for the party and the Uber rides. “You can have that voting bloc that will take ownership of your community.” Across the nation, that younger generation, the millennial generation, is rising. It is the most diverse generation in American history, and also the largest generation in the workforce. Millennials have the ability to reshape American politics in their image — though they also deeply mistrust national institutions, scarred as they have been by entering the economy during the worst recession in nearly a century. This is the fifth story in The Hill’s Changing America series, in which we explore the two sets of divergent trends shaping the country today: The rise of the millennial generation, contrasted with the changing political behavior of older voters who make up the largest bloc within the electorate, and the growing importance of urban America, contrasted with the slow decline of rural economies. The millennial generation, those born roughly between the mid 1980s and late 1990s, has been defined by the circumstances of its birth and the circumstances of its coming of age. And as it matures and begins playing a bigger role in national elections, it will in turn define the future of America. No generation in American history has been as diverse; just 55.8 percent of millennials are white, compared with 75 percent of the baby-boom generation. That diversity is fueled by rising birth rates among African-Americans, Hispanics and Asian-Americans and by declining birth rates among whites. In 10 states, including Texas, Georgia, Florida and Arizona, more than half of millennials are non-white. That diversity has made the millennial generation notably more accepting of liberal cultural views. Younger voters are overwhelmingly more likely to tell pollsters they think homosexuality should be accepted by society, that immigrants strengthen the country and that corporations make too much money. As a consequence, the partisan gap among millennial voters is larger than it is among any other generation. Millennials identify as Democrats or Democratic-leaning independents by a 21-point margin, 57 percent to 36 percent, according to Pew Research Center surveys. Those in Generation X favor Democrats by 6 points, boomers pick Republicans by 4 points and members of the silent generation side with the GOP by a 13-point margin. There is evidence, too, that millennials have been uniquely turned off by President Trump: A Pew survey conducted in March found that nearly a quarter of millennials who identified as Republicans back in 2015 had defected from the party in the intervening years, far more than any other cohort had abandoned either party. “That’s a number that’s going to be coming up at Republican donor meetings,” said Rob Griffin, a demographer at George Washington University and the Center for American Progress. “Stuff like that should terrify them.” That gives Democrats a demographic advantage that should pay off in the long run, as millennials make up an increasing share of the voting electorate. But how long that long run is depends on the party’s success in getting its voters to the polls, something that eluded Hillary ClintonHillary Diane Rodham ClintonWhite House accuses Biden of pushing ‘conspiracy theories’ with Trump election claim Biden courts younger voters — who have been a weakness Trayvon Martin’s mother Sybrina Fulton qualifies to run for county commissioner in Florida MORE’s presidential campaign in 2016. “The bad news is they’re very young and they don’t turn out to vote,” Griffin said. Indeed, in the 2016 elections, a marked decline in turnout among millennials is one of the reasons Trump beat Clinton. Post-election analysis conducted by TargetSmart, a Democratic data analytics firm, found turnout among Democratic voters aged 18 to 29 years old cratered 28 percent in Wisconsin, 11 percent in Florida and 25 percent in Ohio. The fall-off was particularly pronounced among younger African-American voters, who made up such a key pillar of former President Barack ObamaBarack Hussein ObamaHarris grapples with defund the police movement amid veep talk Five ways America would take a hard left under Joe Biden Valerie Jarrett: ‘Democracy depends upon having law enforcement’ MORE’s coalition. Millennials have been slower to engage in civic activities like voting and volunteering, many believe, because of the circumstances they faced when they came of age. It is a generation whose economic prospects have been defined by the Great Recession, which effectively delayed life decisions other generations made years earlier. “We’re seeing a big shift in how families operate, how they’re constituted,” said Karen McGrath, coauthor of “The Millennial Mindset” and a communications professor at the College of St. Rose. Today, more millennials live with their parents than are married or cohabitating with a partner, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. The average age at which a millennial first gets married is rising, too: In 1976, 85 percent of women and 75 percent of men had been married by age 29. Today, only 46 percent of women and 32 percent of men said they were married before they turned 30. Just 70 percent of men between the ages of 18 and 34 have jobs, down from 84 percent in 1960. They are much more likely to have college degrees than earlier generations — nearly 40 percent of millennial women have a bachelor’s degree, and so do more than a third of millennial men. “Previous generations were much more focused on forming a new family, finding a partner, having children, as well as work, buying a house,” said Richard Fry, a labor economist at the Pew Research Center. The decision to delay entering the workforce to pursue a college degree, even as college costs spike to new heights, is a smart one, Fry said. Millennials with a college degree are making more money now than members of previous generations with a college degree, while those who have only a high school education make less than their predecessors at the same age. “The real economic stress here is on those that don’t have a bachelor’s degree,” Fry said. “College is still a pretty good lifetime investment. Delays in forming new families and entering the workforce are also factors in another delay: Fewer millennials own homes than earlier generations did by this point. Fry said the booming housing market has driven up prices, and a tightening mortgage market after the recession has raised the barrier to entry by requiring more money for down payments. The average millennial household has liquid assets of just $3,000 to $4,000. The average college graduate carries tens of thousands of dollars in student debt, further delaying his or her ability to buy a home. “They’re just starting the wealth accumulation phase” of their lives, he said. The economic and social stresses placed on millennials’ shoulders has conspired to delay their civic engagement. “To be a citizen means something different now to this group,” McGrath said. Just 48.9 percent of Millennials of voting age turned out in 2016, compared with 68.5 percent turnout among baby boomers, according to Michael McDonald, a University of Florida political scientist who studies turnout trends. Millennials made up 31.1 percent of all eligible voters, but just 26.7 percent of actual votes cast. The future of the Obama coalition gets brighter as more millennials visit the ballot box, but turning them out to vote is the riddle none but the Obama campaign has been able to solve. What worked for Obama has yet to work for any other Democrat, said Tom Bonier, who runs TargetSmart. “The issue that Democrats face is there’s probably at least a decade gap in there until this becomes a viable path to an Electoral College victory,” Bonier said. Click Here: Bape Kid 1st Camo Ape Head rompers

You May Also Like

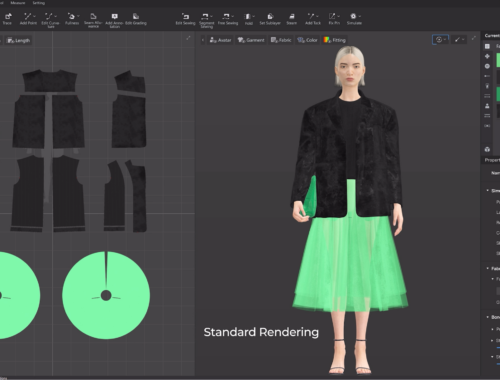

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability

February 28, 2025