The Importance of Teaching Children Hard Lessons

>

Caden Fuchs can’t tell me what he did in the sweat lodge. “It’s secret,” says the 14-year-old. “But,” he offers, “it’s a little bit like I went in a boy and came out a man.”

A statement like that might freak some parents out, but Caden’s folks rolled with it. They knew he was out there with a tight group of friends and a few trusted adults in a Northern California outdoor program called Vilda. The mysterious sweat lodge was part of a yearlong coming-of-age curriculum that also included backpacking, leadership skills, a 24-hour solo fast, and an emotional ceremony with all the parents.

Caden’s belief that something profound about him had changed was very much on target. In many ways, he was intentionally and thoughtfully leaving behind parts of his childhood. He still loves pizza and T-shirts emblazoned with skateboard logos. He has longish dark blond hair that he expertly maneuvers with a quick head flip. And yet, after the Vilda program, the eighth-grader now helps out more at home without being asked. He has taken on strenuous chores, is kinder to his younger siblings, and is more expressive about how grateful he is to his parents.

By guiding middle schoolers through coming-of-age rituals in nature, programs like Vilda are filling a critical gap. Outward Bound offers “solos” of up to several nights alone as part of the curriculum, and smaller outfits like the School of Lost Borders, in California, and Washington’s Wilderness Awareness School focus on rites of passage. Marin Academy, a private school in San Rafael, California, offers a Wilderness Quest program to high school juniors and seniors.

Not so long ago, American kids took a pathway to becoming grown-ups that included a series of rigorous and rewarding steps: increasingly challenging labor on farms or at home, their first fish and first hunt, permission to roam over a zone wider than the driveway. While ceremonies like bar mitzvahs and quinceañeras—and, to some extent, qualifying for a driver’s license—still serve to initiate children into adulthood, we’ve replaced numerous other rites of passage with just one: a kid’s first smartphone.

In his 2009 book Manhood for Amateurs, Michael Chabon wrote,“Childhood is, or has been, or ought to be, the great original adventure, a tale of privation, courage, constant vigilance, danger, and sometimes calamity.” But instead of having their own outdoor exploits and learning to sort out their own problems, modern kids, we all realize, are increasingly domesticated.

Adolescence has become almost pathologized. Teens are basically self-destructive half-wits, the current wisdom tells us; without a fully formed prefrontal cortex, they lack judgment and take stupid risks. Many do, of course, but a far bigger problem today is that teens are taking too few worthwhile risks and assuming too little responsibility. And because they’re not learning through exploration—the way teen brains were designed to learn—they’re not developing the emotional skills they desperately need. Our changing culture has knocked away the scaffolding that used to provide formative and enriching adventures. So what do we do now?

David Sobel, a professor of education at Antioch University, is a proponent of resurrecting meaningful nature-based rituals. Without them, he says, teens are in danger of “overinfantilization, extended childhood, or excessive nonmodulated risk-taking.”

For centuries, traditional rites of passage encompassed everything from slaying beasts to offering up one’s own flesh for mutilation. Across cultures, certain elements remained remarkably stable: a phase of separation and isolation, a period of transformation through trial and reflection, and a celebratory reintegration into the community. “The point is to endure some hardship,” says Sobel, “and that prepares you for adult responsibility, because being an adult is hard. It tests your mettle, it tests your capacity to persist in the face of difficulty. Young people have lost that.”

To help kids regain it, some parents are creating rituals of their own. Allen Jones, a dad in western Washington, is the author of Boys to Men: The Lost Art of Rite of Passage. When both his sons were in middle school, he recruited men from the community to write them letters about their values; formal discussions ensued around sex, work, and spirituality. Over the course of a year, father and son would go on outdoor excursions, culminating in a tough final climb up 12,300-foot Mount Adams. “I grew up without much direction from my father,” says Jones, who began experimenting with drugs and alcohol when he was 13. “My goal was for my boys to not be like me.”

The Lawlor family of Helena, Montana, initiated all three daughters into big-game hunting. Starting when they were five or six, they’d accompany their father, uncle, and grandfather on multi-day elk and deer hunts. Once they were old enough to get hunting licenses, at ten or twelve, the girls would hike miles with the Winchester rifles given to them at birth, lying in the snow waiting for their quarry. They’d help quarter and pack out the animal, learning to practice respect by using every edible part. Tess Lawlor, now 13, hung her first buck skull in her room amid her stuffed animals and floral quilt. The hardest part, says the soccer midfielder and diehard fan of British cooking shows, is pulling the trigger. But, she adds, “It makes me feel more grown-up, and I feel proud about providing meat for my friends and family.”

Parents need to think about how to put wildness back into childhood. One first step is to introduce periodic technology fasts (if not caloric ones). With less to keep them indoors, kids naturally look outside, where nature can become a comfortable, adventurous, and wisdom-yielding space during times of transition and growth.

Another is to bake in some significant milestones. To commemorate their son Johnny’s 13th birthday last year, the Frieder-Stanzione family of Boulder, Colorado, arranged for him to climb a six-pitch route in the local Flatirons with a guide. A few months later, he competed a mountain-bike race, 24 Hours in the Enchanted Forest, finding his way alone, at night, through 13 miles of New Mexico’s Zuni Mountains. “We’re so protective as parents,” says his mom, Julie Frieder. “Here he could be in a risky situation, and the risk is so fundamental to his maturing. This was raw risk and shivery fear. I wanted him to be in that situation.”

Johnny repeated the ride this year, bringing along his favorite stuffed animal, a move that illustrates the transition he’s still in. Next year, he and three friends plan to hike California’s 220-mile John Muir Trail for two weeks by themselves.

Frieder describes these rituals as a kind of inoculation. “Life dishes out scary things,” she says, “things you can’t plan for. If you get crushed, how are you going to experience the world, and get stronger and open yourself to possibility? I want him to know some fear and loneliness and happiness and elation.”

Contributing editor Florence Williams (@flowill) is the author of The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative.

You May Also Like

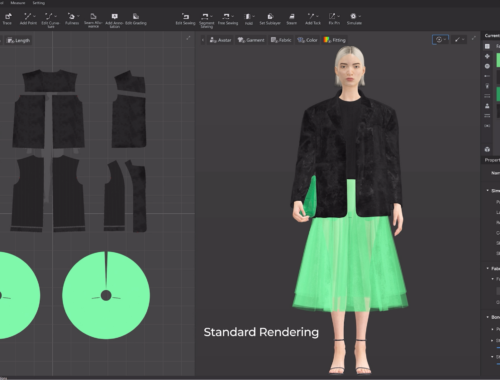

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

Automatic Weather Station: Real-Time Environmental Monitoring and Data Collection

March 14, 2025