As CEOs Pledge Climate Action, Governments Must Ensure They Follow Through

Corporations want to be the new climate saviors. The idea may seem contradictory, given that fossil fuel capitalism is largely responsible for driving the world toward this crisis. Yet in headline after headline, companies are trying to take on a more heroic role by announcing sweeping, ambitious climate plans.

As the consequences of the climate crisis are becoming clearer and the public is becoming more aware of them, there seems to have been a shift in the business world. Larry Fink, founder and chief executive of Wall Street giant BlackRock, wrote in his 2020 letter to industry CEOs: “Climate change has become a defining factor in companies’ long-term prospects. … I believe we are on the edge of a fundamental reshaping of finance.”

Fink’s concern about climate change reflects a broader awakening in the corporate community to the risks and opportunities posed by our warming world.More than 200 companies, including Apple and Coca-Cola, have now pledged to get all of their energy from renewables. Microsoft recently set out a plan to become carbon negative by 2030 and to remove from the atmosphere all the carbon the company has emitted since its founding by the year 2050. Oil giant BP announced plans to go net-zero by 2050, Amazon pledged to go carbon-neutral by 2040, andGoldman Sachs recently announced it would stop funding Arctic drilling.

These voluntary announcements come amid a vacuum in government action. Last year closed with country leaders failing to make progress on tackling climate change at the U.N. climate conference in Madrid. In the U.S., the past four years have seen the Trump administration target 95 different environmental laws for elimination ― including things some industries don’t want, such as rollbacks of laws cutting mercury pollution, or haven’t even asked for, such as attempts to lower fuel emissions standards.

It seems that as government regulations and expectations wane, some companies are feeling the pressure to fill the void with their own plans to slash emissions.

The potential for success ― and failure ― is huge. If corporate leaders follow through on their pledges, the business community could start to reshape global markets and reduce carbon emissions dramatically worldwide.

But experts in the sustainable business world worry about just how much businesses can achieve in the absence of rigorous accountability. Added to this is the challenge of evaluating the success of vague, broad promises that lack detail about timeframes and methods of implementation. And even if businesses do succeed, corporate action alone will not be enough if governments are not also prepared to adopt strong policies to deal with the urgency and full scope of the climate crisis.

Since the Industrial Revolution, greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels have already caused the planet to warm by about 1 degree Celsius, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In the next 10 to 30 years, scientists expect the planet will warm by another 0.5 C. Limiting warming at or below that 1.5 C mark could help us mitigate some of the worst effects of global climate change and protect fragile ecosystems from disappearing. Doing so means we need to start to slash greenhouse gas emissions immediately — and start removing historical emissions from the atmosphere, according to the IPCC.

Over the last five years, concerns about climate risks have finally started getting real attention in the business world, said Sue Reid, vice president of climate and energy at Ceres, a nonprofit that works with companies and investors to drive economic solutions to tackle environmental issues. “We’re seeing a lot more momentum,” she said.

There are some common themes that companies seem to be responding to, according to Reid. These include the effects of climate change on corporate bottom lines, the boost action can have on their profit margins, and the consumer and shareholder pressure increasingly coming from younger, more climate-conscious generations.

Many industries are already feeling the effects of climate change on their supply chains. Between April 2017 and April 2018, 73 companies in the S&P 500 reported that drought, cold snaps, excessive precipitation and other weather events had hurt their earnings. And investors are starting to realize that their assumptions about the economy’s future hinge on the misapprehensionthat the climate will remain stable and predictable, as it has over the last 10,000 years.

“What they’re seeing more and more is that inaction is a very costly proposition,” said Bruno Sarda, president of CDP North America, a nonprofit that runs aglobal environmental disclosure system.

The pressure isn’t just coming from extreme weather. Increasingly, concerned shareholders are starting to flex their power. Pension funds, for example, are large shareholders that make investments in order to provide retirement income.The investment strategy of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System’s (CalPERS), the largest defined benefits public pension fund in the United States, prioritizes sustainability and scrutinizes the climate risk its investments are exposed to. This is entirely because of the “systemic” investment risk posed by climate change, said Anne Simpson, investment director at CalPERS.

Investor networks, likeClimate Action 100+, also put pressure on corporations that emit the most greenhouse gases to take action against climate change. And as Fink’s letter indicates, giants like BlackRock are signaling that they, too, need to take these risks into account.

RELATED

-

Jeff Bezos Commits $10 Billon To Save The Earth From Climate Change

-

Greta Thunberg Throws Shade At Trudeau For 'Climate Hypocrisy'

-

Climate Change Will Lead To Greater Risk Of Wildfires In Canada: Experts

There are also signs that taking steps to decarbonize is good for business, according to Sarda. Of all the companies that disclose their climate action plans to CDP, theA List group with the most aggressive science-based targets to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions have outperformed their global benchmarks in the stock market by 5.5 per cent annually over a seven-year period, he said.

Millennials may also be key to inspiring corporate climate action, said David Webber, professor of law at Boston University who studies shareholder activism. Millennials currently make up the largest percentage of the U.S. workforce and are much more likely to care about climate action taken by their employers than boomers or Gen Xers.

They are also the future of wealth investing, said Webber. If investment companies want to compete for millennial dollars, they may need to prove themselves environmentally responsible first, he said.

This was made stunningly clear by CNBC’s Jim Cramer, host of “Mad Money,” at the beginning of February. Responding to the fourth-quarter earnings reports released by oil majors showing a continued decline in stock prices, Cramer said, “I’m done with fossil fuels. They’re done. They’re just done.”

Why? “We’re starting to see divestment all over the world,” he added. “We’re starting to see big pension funds say, ‘Listen, we’re not going to own them anymore.’ … The world’s changed.”

When enough companies take decisive action, they can reduce carbon emissions on the scale of a large country, said Sarda. For example, if just 285 companies are able to reach the targets approved by the Science-Based Targets Initiative (of which CDP is a part), they would mitigate 265 million tons of CO2, equivalent to closing 68 coal-fired power plants. If those companies eventually eliminated all their greenhouse gas emissions, they would mitigate 752 million tons of CO2, more than France and Spain emit every year combined, he said.

While that scale is impressive, it’s not nearly enough, Sarda said. We need many more businesses taking swift and decisive action and we need them all to be moving much, much faster, he argued.

Not every industry is rushing to rally behind climate action. For some corporations, reckoning with climate goals would mean questioning their entire business model. In many cases, these same companies still hold a lot of financial and political power.

While oil and gas companies have highlighted their renewable energy commitments inrecent advertising blitzes, the overwhelming majority of their investments are still in fossil fuel development ― in 2018, oil companies collectively spent one per cent of their annual budgets on renewable energy. The plastics industry, which relies heavily on fossil fuels, is alsogrowing quickly.

Climate pledges can make for good publicity, but they don’t always show the full picture. According to reporting in the climate newsletter Heated, Microsoft still donates to the political campaign of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), who famously favors fossil fuel interests. Microsoft declined to comment to HuffPost.

And althoughAmazon has committed to 100 per cent renewable energy and achieving carbon neutrality within 20 years — and Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos has pledged US$10 billion in grants to fund climate projects — the company provides the fossil fuel industry with vital cloud computing services. An Amazon spokesperson directed HuffPost to the company’s website, which says that Amazon is helping energy companies reduce their carbon emissions and aiding their transition to renewable energy by supplying these services.

Amazon employees ― who have been fighting for their employer to do more to address climate change ― issued a statement saying that Amazon funds climate denial groups and attempts to silence internal criticism.

BP, which announced arguably the most ambitious climate plan by an oil company in February, has also generated some skepticism.

The British fossil fuel major pledged to eliminate or offset all of its operational emissions, along with those caused by the extraction of oil and gas, by 2050. At a news conference to announce the plan, BP’s chief executive, Bernard Looney, said, “We are aiming to earn back the trust of society. We have got to change, and change profoundly.”

Amid some cautious praise from environmental groups, many were quick to point out that BP’s plan lacked details on how exactly it would achieve its targets. Some groups said they wouldn’t take any oil company’s climate promise seriously if it didn’t include a commitment to stop expanding the extraction of fossil fuels from the ground. A BP spokesperson told HuffPost that the company’s new chief executive has a clear vision to “restructure the company” and that a more detailed plan will be released in September.

It remains to be seen whether companies that have committed to tackling climate change will actually be able to translate their pledges into material action. This is all the more important because the stakes are so high. To avoid climate catastrophe, global emissions must fall by 7.6 per cent every year for the next 10 years, according to the U.N.

“We need to make sure — and that’s the role disclosure plays — we need to make sure that we don’t find out in 2030 that they’re nowhere,” Sarda said.

That is what happened with companies that made voluntary pledges to reduce or eliminate deforestation in their supply chains by 2020, he explained. Earlier this year, the nonprofit Global Canopy found in its annual report that companies have mostly failed to follow through on declarations to meaningfully reduce deforestation.

Transparency, disclosure and concrete action plans are key to ensuring these targets go from rhetoric to action, said Sarda. CDP tries to provide oversight, he adds, with its global disclosure system that invites companies, shareholders and local and regional governments to voluntarily declare and manage their environmental impacts.

Third-party pressure is crucial to encourage businesses to follow through and hold them accountable for their commitments, said Webber. And that pressure needs to come from all fronts — nonprofits, activist shareholders and socially responsible investors, consumers, employees, millennials, and more, he added.

“We have seen a lot of commitments from companies, and some companies are putting in a good-faith effort to achieving [their renewable energy goals,]” said Amanda Levin, a policy analyst at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “Others may need an additional push to actually implement the measures to achieve those targets.”

Pressure also needs to come from policymakers, said Webber, adding that both the private and public sectors have roles to play when it comes to tackling climate change.

Watch: Canadian advocates call for unprecedented climate action. Story continues below.

Research from the World Resources Institute found that when the government sets targets and creates legislation on climate change action, it assures businesses that they are making the smart business decision. Federal policy can support much-needed research on clean energy technologies, create regulations that incentivize or force companies to reduce emissions or work with companies on a voluntary basis to do so, and create market-based solutions that put a price on carbon and help create a decarbonized economy.

But even though cities and at least 25 state governments are prioritizing climate commitments and the shift to a greener economy, federal climate policy is a nonstarter under the current U.S. administration. President Donald Trump pulled the United States out of the Paris climate agreement early in his tenure and has been very vocal in his support for the fossil fuel industry. The White House Management and Budget Office’s proposed budget for 2021 includes sweeping cuts to scientific agencies, including NASA, the Energy Department and the Environmental Protection Agency.

So, can businesses fill the void left by government leadership right now? “The answer is they have to,” Sarda said. “The countdown to 2030 has begun… the clock is ticking and we can’t not be successful.”

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to [email protected].

You May Also Like

China’s Leading Pool Supplies Manufacturer and Exporter

March 18, 2025

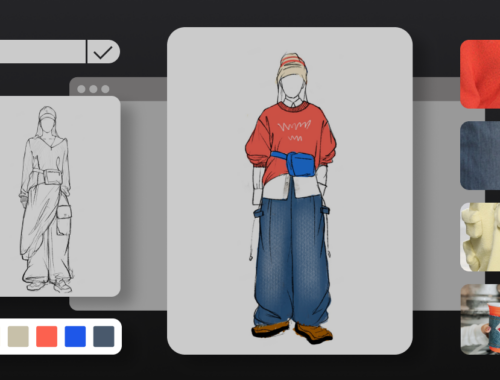

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability

February 28, 2025