Notes on My Queer Bromance with My Personal Trainer

>

One Thursday evening last summer, my personal trainer, with a wild look in her eye, whipped out a red resistance band. “I thought of a genius way to help with your push-up problem,” Andrea (not her real name) told me, grinning with the cockiness bestowed upon so many lesbians in their early twenties. She slid the red band over my head and around my waist, then instructed me to get into push-up position. I did, nervous about where this was going.

We’d been training together twice a week for four months, and I still couldn’t complete a full set of standard push-ups without breaking form or giving up. I was an athletic kid growing up: I played soccer until I could no longer deny my coordination deficiency, then ditched that for track and cross-country. But the push-up had always eluded me. At age 27, my metabolism had done an Irish exit, and I decided I wanted to learn how to lift properly. I figured getting a trainer would be the best way to attain real upper-body strength. And overall, I’d achieved that goal. I’d been bench pressing and reverse pulling my way to self-confidence, but push-ups were still my white whale. I would always give out after seven or eight—left like a sad, half-dead fish flopping around on the deck.

Thank God I had Andrea, a 22-year-old divorcée (yeah) whose diet consisted primarily of Muscle Milk and McDonald’s. She stood over me, holding one end of the resistance band wrapped around my middleas I struggled to simply hold the push-up position. “Okay, let’s start with ten.” I did, and for the first time, I completed a full set of push-ups in perfect form, chest bouncing effortlessly back up with significant aid from the giant rubber band. I felt like the ultimate sub in some kinky, workout-centric foreplay that I had somehow consented to, for the entire gym to see. It was deeply demoralizing in the moment, but the second it was over I felt like I’d come one step closer to achieving my fitness goal. My face burned with embarrassment and pride. It was complicated.

Andrea was my trainer for about ten months at a no-frills, second-floor gym that didn’t hide how broke it was. The owner would send weekly all-caps text blasts to its members—RENEW NOW FOR 6 MONTHS FOR JUST $180! or LABOR DAY SALE! ONE YEAR MEMBERSHIP FOR JUST $360!—that all came out to about $30 per month. (I shouldn’t have been surprised when, one Monday in February, the Chicago Police Department entered and instructed sweaty gym-goers to cease pumping iron because the business was being evicted.) The training sessions, too, were pretty cheap.

Andrea had a spindly, athletic frame and a swagger that I had some version of when I was 22. (She also had short hair, dyed light purple, with the gym’s initials buzzed into the sides of her head.) I didn’t request Andrea as my trainer because I was into her, but I did request her because of how she looked. Everyone else at the gym presented so aggressively heterosexual that I felt overwhelmed, like I wasn’t supposed to be there. But for being two lesbians spending 100 percent of our time together all sweaty, in kink-adjacent apparatuses like the resistance band/push-up situation, I cannot overemphasize the complete lack of sexual tension between Andrea and me. We simply weren’t each others’ types. Which is to say, I wasn’t hot enough for her—thank God.

In our first session, Andrea and I chatted about our athletic histories. When I told her I ran track, she nodded and asked, “You sure you didn’t play, like, softball or rugby or basketball?” I didn’t have a purple buzz cut, so she was trying to suss me out. I grinned. “Oh, you mean the gay sports? Unfortunately, no.” She spent the remainder of our months training together trying to convince me to join her rugby team. If the gym hadn’t been evicted, I may have eventually joined.

A friendship quickly developed from there—if you can really be friends with someone you pay for a service. We were both born and raised in Chicago in gigantic Catholic families, but the surface-level similarities ended there. I grew up in an affluent north side neighborhood, Andrea in a now-gentrified Puerto Rican neighborhood on the west side. I was that cliché white-girl-with-bangs-studying-queer-theory-at-liberal-arts-college lesbian, and she had an associate’s degree and part ownership in her own gym franchise. For what Andrea lacked in Judith Butler familiarity, she more than made up for in bodybuilding wisdom. She often pointed out hot girls at the gym in a bro-to-bro kind of way, and I’d say something like, “Haha, hope she has a nice sense of humor.” She’d roll her eyes at me. I hide my feelings under a coat of sarcasm, and Andrea possessed an earnestness I envy.

Andrea spoke with certainty, a feigned wisdom beyond her years that so many folks do in their early twenties. It’s an age where we feel we’ve experienced enough to know the way the world is, but not enough to feel overwhelmed by the diverse complications of adulthood. It turns out an injection of 22-year-old cockiness was exactly what I needed. Especially at the gym.

Within months, I realized Andrea looked up to me as a sort of big-sister figure. I was an old, boring 27-year-old, basically geriatric in her eyes, with the wisdom of an ancient sapphic tree. “Oh God, so much has happened since I saw you last,” she’d say at the beginning of each session, before absentmindedly instructing me to do some deadlifts. Her chatter ranged from the high stakes (sharing updates about her family in Puerto Rico post-hurricane) to the low stakes (what to get her girlfriend’s dad for Christmas—not a fishing shirt that read “Master Baiter,” at my begging) to the adorable (stories about her four dogs, cat, and ferret). It was a welcome distraction from the mess that is me trying to do push-ups. In exchange for my ear, Andrea showed me it’s possible to have muscles in your back.

One session in December, Andrea led with a loaded question: “When do you know when someone’s not really your friend?” I was so charmed! From someone with such confidence and swagger, this was such a childish, intimate question. It has such obvious answers for kids—bullies aren’t your friends, your friends are the people who always have your back—that get obscured over time by the complications of adulthood. She gave me more context: Andrea had become close friends with a client, to the point of training her at no charge. Now Andrea suspected the client was only using her for free training sessions and weed. (Andrea lives a lifestyle that only 22-year-olds can pull off while maintaining 1 percent body fat.)

I told her to cut the client off, with a firm explanation that she needed to be paid for her service. We volleyed back and forth. Andrea didn’t want to lose the client as a friend. From someone who’d literally been married—a level of commitment still overwhelming for me to consider as I approach 30—it was surprising to hear Andrea wrestle with the definition of genuine friendship. I, in very motherly form, told Andrea, “She’s not your real friend if she treats you like this.” Condescending? Maybe. But something even grown-ass adults need to be reminded of from time to time.

Gyms are a strange bastion of intimidation. Jacked dudes grunting with every rep, stick-thin blondes waltzing into yoga class, leering eyes everywhere. It’s easy to feel bad about your body in that setting. Growing up playing sports, I was really only used to working out with other girls, typically at the same level of fitness as I was. That security blanket doesn’t exist at the grown-up gym. Being tethered to someone who presented as gay as Andrea did made me feel more confident at the gym, like a safety-in-numbers thing. Queer folks routinely have to carve our their own space in heteronormative communities for this reason, at work or school or even within extended families. Turns out my hole-in-the-wall fitness center was no exception.

LGBTQ folks often talk about their “queer family.” Being gay isn’t just about finding someone to date. It’s about building that family, the friendships that instill themselves into your bones and allow you to love yourself. Queerness makes way for connections much more far-reaching and meaningful than simply the romantic or sexual.

I’d be romanticizing if I claimed Andrea and I made our way into each others’ queer families. But until the landlord sued the gym for $200,000 in overdue rent, my trainer and I did bolster each others’ lesbian identities. I paid her, and she showed me how to deadlift; I gave her romantic advice, and she made me feel confident having a queer body in a largely straight space; I told her how friendship works, and she put me in a giant rubber band so I could actually do a push-up. It felt a bit like therapy. You feel like you’re creating a meaningful relationship with a person over the course of an hour, sharing your deepest darkest secrets, and then the session’s up—and you fork over the cash.

You May Also Like

シャーシ設計の最適化手法とその応用

March 20, 2025

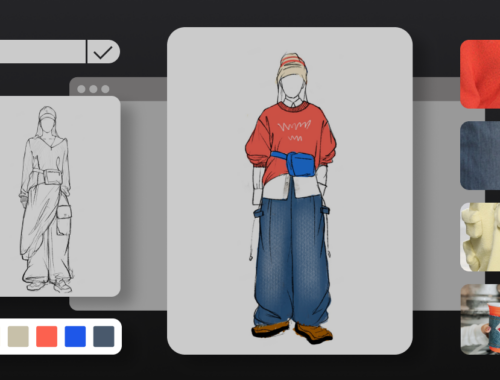

AI in Fashion: Redefining Design, Personalization, and Sustainability for the Future

March 1, 2025