What Happens to Your Body on a Long-Distance Swim

>

Ross Edgley, a British athlete and fitness enthusiast, is currently on a mission to swim 2,000 miles around the coast of Great Britain. That means spending 12 hours a day in cold, sea jelly–filled currents. The feat has been a dream of his since childhood, and after talking to rowers and gauging his ability to work with tides, Edgley realized it just might be possible. “People have run around Great Britain, they’ve sailed around it, they’ve cycled around it, but no one has ever swam all the way around,” he says.

When he set out on June 1,Edgley planned to complete the swim in 100 days. Due to stormy weather and unfavorable tides, he now expects it to take about 145 days—putting him back on land in late October. He’s swimming two six-hour stints per day and returning to the support boat to eat and sleep in between.

Unique strength and endurance challenges are kind of Edgley’s schtick. The 32-year-old completed a marathon while pulling a Mini, climbed 29,029 feet of rope (equivalent to the height of Everest), and swam more than 60 miles with a 100-pound log in tow.

We caught up with Edgley on day 74 of his swim, when he had just broken the record for the longest consecutive period swimming at sea. (Benoît Lecomte set the previous record, 73 days, in 1998.) While he seemed surprisingly unfazed about spending hours alone and sloshing through seawater, a long-distance swim of such epic proportions can take a serious toll on the body. Here’s an overview of what Edgley has endured.

Edgley says that some of the most painful effects of the swim have been to his skin. As he breathes in salty air and water, salt covers his tongue, causing it to swell. Three weeks in, he woke up to chunks of his tongue on his pillow, and he had trouble talking. Spicy foods became painful to eat. Edgley later found that rinsing with mouthwash and coating his mouth with a layer of coconut oil protected it from the salt.

Edgley also experienced painful chafing—his wetsuit rubbed the back of his neck raw. He’s since developed a callused “rhino” neck.

Beyond these extreme examples, even small cuts at sea can be a big problem. Saltwater prevents scabs from forming, leading long-distance swimmers to run the risk of sea ulcers, wounds that can take months to heal and grow deeper over time, forming a rubbery, callous-like edge. After consulting with surfers, who also deal with sea ulcers, Edgley is protecting his cuts with industrial-strength plastic tape to keep seawater out.

The heart, like any muscle, can get tired out. “Extreme endurance athletes have probably a five- or sixfold increase in the risk of atrial fibrillation,” says Benjamin Levine, a professor of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. During atrial fibrillation, the heart’s pumping becomes irregular and less efficient, which can eventually lead to stroke-causing blood clots.

By maintaining a high heart rate over a long period of time, endurance feats can cause the upper, blood-collecting chambers of the heart—the atria—to stretch. Meanwhile, the right ventricle, tasked with pumping, becomes fatigued. The result is sometimes an arrhythmic heartbeat. Long-term swimming, in particular, could pose a risk because the athlete is lying flat instead of standing up; this puts more pressure on the heart, Levine says.

“In ultramarathons, the joints in the legs might give up before [the heart],” says Edgely, who has a degree in exercise science. But with swimming, he says, “It’s the heart that’s going to be the limiting factor.” For his part, he’s been careful to maintain a measured, slow pace. Edgley tries to keep his efforts “completely aerobic,” adding, “You shouldn’t being tapping into your lactic threshold.”

He’s constantly adapting his technique to move with the least possible effort: “I barely kick my legs at all, and it’s just very much a rotation in the upper body…I’m sort of floating efficiently.”

Even with his efficient swimming style, Edgley is burning a ton of energy. To make up for it, he eats about 10,000 to 15,000 calories a day.

In the water, Edgley focuses on quick-digesting carbs, mostly bananas. He’s found that the fruit is easy to eat with salt tongue. Plus, bananas are gentler on the stomach than slower-digesting fatty foods. On a sign hanging from the boat, his captain keeps a running tally of how many bananas Edgley has eaten. (As of mid-October, it was more than 500.)

Once he’s back on the boat, Edgley treats himself to pizza, burgers, and ice cream. “Nothing is off the menu when you’re trying to make up that amount of calories.” Still, he follows the junk food feast with a green smoothie made from Protein Works Super Greens. Edgley says that in more than 100 days of swimming, he hasn’t had to take a sick day.

Monique Ryan, a dietitian and author of Sports Nutrition for Endurance Athletes, agrees that Edgley’s diet is a good approach to fueling this extreme challenge. Carbs, fluid, and electrolytes are the main nutrients the body needs while moving. When Edgley’s on the boat, a meal composed of “half a plate of carbs, a quarter plate of protein, and a quarter plate of fats” will supply what he needs to recover, Ryan says. The follow-up smoothie offers some extra calories and nutrients without taking up too much room in the stomach, which might still be full from the earlier meal.

To be able to swim with the tides, Edgley had to break up his rest periods. He’s adopted a biphasic sleep schedule, snoozing about four hours at night and another three during the day.

It hasn’t been easy sleeping in two chunks. Although he has no trouble drifting off in his tired state, “It’s not seven hours of quality, deep sleep,” Edgley says. “That’s one thing that is challenging—it’s this constant, disruptive sleep.”

“Generally, the more you start divide the sleep up, the less it’s going to do for you,” says Christopher Winter, a sleep specialist and author of The Sleep Solution. What’s more, sleeping during the day is tricky due to the body’s circadian rhythm. While what Edgley is doing isn’t “terribly unsustainable,” it’s not ideal, Winter says.

Long stretches of time alone in the water can take a toll on the mind as well. “If you’re stung by a jellyfish and left alone with your thoughts, [your mind] can go to some pretty dark places,” Edgley says. “One of the biggest predictors of whether this is a success or not will actually be that intangible mental aspect.”

Sensory deprivation, constant pain, and exhaustion all combine in such endurance events, says Frances Klemperer, a psychiatrist at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London who has studied English Channel swimmers. These psychological factors can easily lead to despair and giving up. And when there’s nothing to look at but sky and water for hours, the understimulated mind conjures illusions and hallucinations. To avoid this, Klemperer says, “Trying to occupy the mind is quite important.”

Edgley has developed some strategies for coping with the marine monotony. He reads a lot on the boat and mulls over his books in the water. The key is staying entertained, he says.

“I might make funny noises under the water or laugh at a joke I thought of, or I might be thinking what I’ll have on my pizza when I get out,” Edgley says. “The secret mentally is that there is no secret—it’s about being as creative as possible and occupying the mind with something that bigger than your shoulder hurting or your tongue falling off.”

You May Also Like

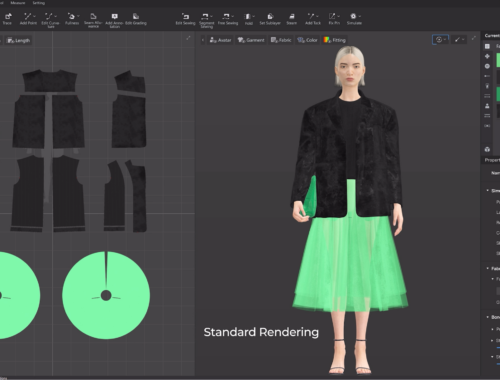

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025

WHY ELECTRIC TRICYCLES FROM CHINA ARE TRANSFORMING GLOBAL TRANSPORTATION: A GUIDE TO CHOOSING THE BEST MODEL

December 31, 2024