How Anna Brones Works Half a Dozen (Cool) Jobs

The writer, cyclist, artist, and producer doesn’t have a secret for getting her art into the world. She just does the work.

In 2018, I started recording interviews with creatives (writers, filmmakers, podcasters, photographers, editors) in the adventure world. I’m publishing the highlights of those interviews monthly in 2019.

When she’s filling out a form with only one line for occupation, Anna Brones puts writer. But if you want the long version of her résumé, you’d need to include things like film producer, artist, publisher, and even culinary creator (which is probably accurate but may not actually be a job title). She’s based in Washington State, is a cyclist, runner, and backpacker, and speaks three languages.

Brones has written six books, including Hello Bicycle: An Inspired Guide to the Two-Wheeled Life, The Culinary Cyclist, and Fika: The Art of the Swedish Coffee Break. She curated, edited, and published Comestible, a quarterly food journal, for three years starting in 2016. And she worked as a producer on several films that screened at festivals around the world: Voyageurs Without Trace, Ian McCluskey’s journey to retrace the 1,000-mile first kayak descent of the Green and Colorado Rivers in 1938; Mending the Line, the story of 90-year-old veteran and angler Frank Moore’s return to Normandy to fish the terrain he saw as a soldier in World War II; and most recently, Afghan Cycles, a documentary feature about young women in Afghanistan who use bikes as revolutionary tools.

In 2018, Brones began her Women’s Wisdom Project, a collection of 100 different paper-cut portraits of inspiring women, created by hand using quotes from figures both contemporary and historical. Already in 2019, she’s started a monthly newsletter, Creative Fuel, to provide a kick in the backside to subscribers.

I first met Brones in 2011 and have always been impressed with her creative output—the quality, quantity, and authenticity. A few years ago she told me, “I feel like most of what I do is hustle.” So I wanted to record one of our conversations and ask a little bit about how she makes it all work.

On Being a Writer: “When someone says, ‘I want to be a writer,’ there are so many ways that you can be a writer. Do you want to write poetry? It’s a little bit different than writing cookbooks, right? Those are two different ball games. And there are so many types of writing. I do nonfiction stuff, and some of it’s a little bit journalistic, some of it’s a little bit lifestyle, so I have a pretty specific thing that I do.”

“No matter what you’re doing, you just have to do it. There’s no easy way into anything, and people take very different paths. Talk to anyone in any industry. I love hearing what people do for a living, mostly because it’s a reminder that there are so many weird jobs out there that you didn’t even know existed. And if you want to write, the best thing that you can do is write.”

On the Power of DIY Books: “I do a lot of self-published stuff, and I’m a big fan of the zine revival—small, super low-budget publications that were big in the eighties punk scene. It’s a platform where you can write something, print it on a piece of paper, and then photocopy it and pass it out to your friends. It’s why I like writing books. It’s why I like making work that’s tangible, because there’s a value and an emotion that comes with it that is really amazing.”

On Self-Publishing, Editing, and Entitlement: “If you want to be a writer, you start by doing it. Now, that’s not to say you’re going be an overnight success. There’s a lot of hard work that goes into it, and it requires input from other people to help you get it to shine. So it’s not as if you just get to vomit your work all over the place and it’s automatically going be successful. The platforms that are available nowadays make it easier, but that also means the market has more people in it. It can be oversaturated sometimes. But there’s really no trick besides doing the work.”

On the Myth of Books and Money: “I think nonwriters, or people who haven’t published before, are like, ‘Oh, you got a book contract?’ and immediately they see dollar signs. But I don’t want anybody to be under the illusion that having a book contract necessarily means that you’re rolling in tons of money.”

On Choosing Interview Subjects: “Every story is important. Everybody has something to tell. That doesn’t mean you need to have lived through the most horrendous accident—I like projects that focus on shared human experience. The second you talk to people, you’re reminded of your similarities, not your differences.”

“I’ve thought a lot about the wisdom we have to offer one another. Often we turn to famous people for wisdom, or famous writers. But I think there’s so much wisdom to be drawn from our counterparts if we just sit down and have a conversation. So now I’m shifting to doing short interviews with friends and acquaintances in various industries to get their perspectives on things.”

On Calling Yourself an Artist: “It’s interesting, what we allow ourselves to call ourselves, the license that we give ourselves to say, ‘I’m a writer’ or ‘I’m an artist.’ Or ‘I’m a producer,’ ‘I’m a filmmaker.’ What is the point we have to get to where we feel comfortable doing that? So many people say, ‘I would never call myself an artist.’ I ask them why. ‘Well, I’ve never sold anything.’ Well, does money justify you calling yourself a thing? Do you do the thing?”

“There’s a great Virginia Woolf quote—‘Money dignifies what is frivolous if unpaid for.’ It’s so interesting, in our culture, that if you sell something, people will be like, ‘Yeah, good job.’ I think the important part about creative work is the fact that you did the work.”

On Having a Creative Childhood: “I grew up in a fairly ‘alternative’ home. We weren’t living in a commune or off the grid or anything like that, but my parents built our house. It’s still not 100 percent finished, because that’s what happens when you build your own house. I played in the forest and ran around barefoot most of the time. I didn’t have any siblings, and we ate a lot of healthy food. I definitely wasn’t able to trade my sandwiches at school during lunch. I wasn’t allowed to watch Sesame Street, because my mom thought the characters yelled too much. So I only watched Mr. Rogers and Captain Kangaroo. I was only allowed to watch public television.”

“My mom is an artist, and she’s a weaver and does a lot of other stuff. So our household was pretty modest—we were a single-income family. But the one thing I did have was all kinds of art supplies. Until I was 13 or 14, I thought it was normal to have those things at home. Then I would go to a friend’s house and be like, ‘Why do you have only five crayons?’ I was always doing creative activities—it was a normal experience for me. And I guess I always wrote.”

On Getting Started in the Business: “After college, I taught English in the Caribbean, in Guadeloupe, and that was when I started writing. It was a hard experience, and I wrote to sort of work through some of my emotions, feeling like I was in a different culture. That was at the beginning of the internet becoming a hot spot for travel writing, and I started submitting articles. I did some stuff for Matador Network; I found them on Craigslist or something. I actually think the first couple of pieces weren’t paid, but then there were a few that were like $10 or $15. About a year after that, I started writing for a travel blog called Gadling. I wrote for them for a long time. It was like ten bucks a post or something.”

“I also did an essay that was published in a book called A Women’s World Again. It was a compilation of travel essays. This was in 2008 or 2007. I wrote an article called ‘Pineapple Tuesday,’ and it was all about living in a small town in Guadeloupe. Guadeloupe is a French overseas department, so it’s like France except that it’s in the Caribbean. It was hard, because the living situation was bad, the work situation was bad, and the friend situation was bad. I often feel those are the three things that, if one of them is bad but the other two are pretty decent, you’re good to go. But if the three of them suck, then it’s a hard time.”

“So every Tuesday after I taught, there was a market I would go to. There was this lady who sold pineapples. She came from a totally different background than I did. She was born and raised on the island and was a farmer. It just became this social exchange where every Tuesday I’d go and buy pineapples from her. So I wrote an essay about it. It was a way to feel grounded in the midst of what didn’t feel like a great experience. That was the first essay I had published in a book.”

On the Line Between Career and Life: “I read this Cheryl Strayed quote the other day, as I was preparing to interview her, and it was something along the lines of ‘Don’t spend so much time focusing on your career. You don’t have a career. You have a life.’ And I thought that was such a good point. Culturally, we put a lot of value on career, and I think it’s a little bit different for people who do creative things. Obviously, there’s a lot of crossover between personal interests and professional interests, but those lines become kind of blurry sometimes. Often the things you do for fun turn into work.”

On the Ups and Downs of Creative Work: “I sometimes feel like I’ve been very bad about creating a sustainable path for myself. I look at my bank account and think, Well, this is all well and good, as long as you’re healthy and able to keep doing stuff. And that can often feel like a failure. One day you’re like, Fuck yeah, I got this. I’m so stoked on what I’m doing. And then the next day, you’re practically curled up in the fetal position on the couch, just bawling. Like, just talking about how terrible you are and… you know, that’s a reality.”

“I struggle a lot with imposter syndrome. And I’ve been trying hard not to. Or to acknowledge it and then kick it in the pants and tell it I don’t have time for that today. Because it ends up holding us back sometimes.”

On Growth Through Creativity: “Something important to keep in mind is that the dollar amount you make off of something is not the be-all and end-all. Of course we need to pay rent and eat, and if you’re working in a creative field, and that’s how you pay rent and eat, you do need to think about making money. However, if there’s work that you feel needs to be in the world, you just do that work.”

“And it’s important, particularly with personal work, to try to separate ourselves from the end result. Often we give so much value to the end product, and usually it’s the process that is the important part. You’re doing the work because the work itself makes you feel a certain way, and you get energized by it, even when it’s hard. There’s so much in that process that’s important, and we often forget that because we’re so focused on the end result.”

On the Value of Work: “There’s a lot of pressure to have all this value in the work that you do. Often I’m like, ‘I want to do something that’s meaningful and impactful.’ But what does that even mean? What are the areas you can have an impact on in your everyday life? Impact happens in very small ways usually.”

“A few times in the past year, people I don’t know have reached out to me and said, ‘I love your work,’ or ‘You brought so much lightness to me this week,’ or ‘Yeah, I had totally not thought about that thing that you talked about. Thank you for bringing it up.’ I mean, I realize that doesn’t pay my rent, but they’re the kind of comments that make me continue to do what I do. And I’m under no illusion that I’m going to change the world. But I think having a positive impact on the people around me is really important.”

You May Also Like

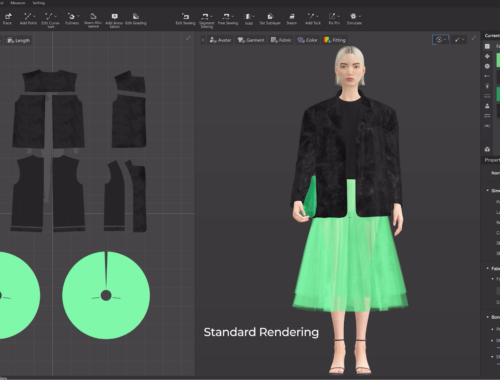

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Sustainability, and Shopping Experiences

February 28, 2025

ユニットハウスのメリットとデメリットを徹底解説

March 22, 2025