A Traveler's Guide to KonMari–ing Your Life

>

When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we earn an affiliate commission that helps pay for our work. Read more about Outside’s affiliate policy.

The hat in my hands is unremarkable: a floppy, full-brimmed sailor’s cap with corroded buttons and wavy lines of salt and sweat. All battle scars from keeping my Irish skin from lobstering in the relentless South Pacific sun on a months-long sailing trip.

Now, a year and a half after my return to dry land, I've divided all of my worldly possessions into two piles on the floor of my bedroom: those to keep on the right, and those to donate on the left. This hat is destined for one or the other. I’m preparing to move from Santa Fe to Denver to start my first full-time gig as a magazine editor after years of internships, freelancer’s paychecks, and backpacking around the globe. The pile on my right needs to be small enough to fit in my car for the journey. The pile on the left will keep growing until it does.

By now I’ve become an expert at fitting my life into small spaces. Over the past five years, I’ve lived in a dozen cities in half a dozen countries, mostly out of a backpack. Bouncing from place to place, I developed a process for winnowing down my possessions that’s remarkably similar to the now famous KonMari method. Developed by self-proclaimed tidying expert Marie Kondo—originally in her 2014 book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up and now in the hit Netflix series—the method posits that reducing clutter in one’s home and life can be a path to happiness, in part by getting rid of items that no longer “spark joy.” Like Kondo’s system, traveling has forced me to reduce my possessions down to the items that are truly important and necessary.

Humans are like gas. Our stuff expands to fill the space we’re given. Every time I would move, I’d have to cull everything I’d acquired to fill my rented room or boat cabin down to what would fit into my backpack or, more recently, a 2001 Toyota Camry. Only, the question I ask myself isn’t, Does this spark joy? It’s, Is it useful?

First I divide my possessions into broad categories like clothes, outdoor gear, or electronics. Subcategories such as T-shirts, jeans, and climbing equipment follow, each laid out in neat piles. From there it’s easy to see where I have too much stuff, and I start culling the largest pile. I keep a few things in mind: How well does each item work? How often do I use it? Do I have two or more belongings that perform a similar function? If I waver on the answer, the offending object is in danger of being tossed. By the time I’m through, I’m left with only what’s best and most vital. A small first-aid kit, camera, waterproof jacket, multitool, dive mask, and my Kindle loaded up with books and guides always seem to make the cut.

I wasn’t always this ruthless purger. As a kid, my dad nicknamed me Hector the Collector after my penchant for hanging on to anything and everything. My bedroom was bursting with junk—rocks, shells, paperclips, stickers, anything that I’d imbued with some sort of significant meaning. On my first international trip, 20-year-old me hauled two giant suitcases, a duffel bag, and a backpack, each filled to the brim with important things I “needed” for six months of studying in South Africa. If not for the subsequent years spent as a nomad, my life could have come to resemble Hoarders rather than Kondo’s new reality show.

In June 2014, not long after I’d left South Africa and four months before Kondo published the book that would skyrocket her to fame, I purchased a one-way ticket to Southeast Asia, figuring I’d spend about three months working for a small conservation organization in the jungles of Borneo. Three months turned into three and a half years of globe-trotting, and while many of the ways traveling changed me were subtle, returning home to my parents’ house for the first time after that journey was a shock. I found my bedroom filled with everything from useless college textbooks to glittery middle school capris that no longer fit. I was face to face with my old self, and I hated it. The strong sentimental attachment I’d once given these things was gone. In its place, I found that I now feared my ability to pack up and leave at a moment’s notice. By the end of the week, I had rid myself of about 80 percent of everything I owned.

Now, as I’m purging for one more move and the possible end of my rambling days, the lessons I learned on the road bring a certain lightness to my life, even when I’m stationary. You can live off a lot less than you think, and memories don’t take up any space at all.

Considering this, I look back down at my hat. I fondly remember long days on the water, but I also I recall its all too floppy brim and tendency to be whisked off my head in stiff breezes. Then I eye the next item—a new, almost identical hat I’d been gifted from a friend, this one with a rigid brim and lightweight fabric that keeps my head cool even on long summer hikes. So, as Kondo instructs, I thanked my old hat for its service and the times we’d spent together and tossed it to the left.

You May Also Like

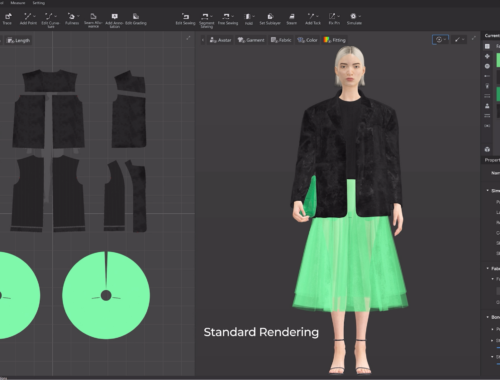

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

China’s Leading Pool Supplies Manufacturer & Supplier

March 25, 2025