Cuba’s female fighters want an equal shot

New generation challenging nation’s official men-only policy for the ring

HAVANA – In the musty funk of a boxing gym in the heart of Cuba’s capital, Idamelys Moreno pounds a series of right hooks into a heavy punching bag.

For the past four years, she has ripped it up in training to try to emulate dozens of Cuban men in winning Olympic gold in the ring.

But Moreno and other talented women are punching not so much a glass ceiling as a glass wall: In Cuba, only men can fight in boxing tournaments.

“They haven’t given us our chance,” fumes the muscular 27-year-old with burning ambition and a simmering frustration.

Ducking and feinting, her stance constantly shifts as she works her way around the swinging bag, the room echoing her heavy blows.

The island’s boxing greats beam down from posters on the walls, among them three-time Olympic heavyweight champion Teofilo Stevenson.

“She’s a boxer with a lot of enthusiasm and enormous physical capacities, but she is nowhere near her full potential yet,” said her coach Emilio Correa, who won silver at the 2008 Beijing Olympics and gold at the 2005 world amateur championships.

Cubans are justifiably proud of their unique boxing tradition, which has brought a haul of 37 Olympic golds and 76 world championships medals – all won by men.

“If they’d give us the opportunity, we can also build on the medal collection that the men have won,” said featherweight Moreno, whose punching prowess has been honed by sparring with men.

She is not the only woman working the bags.

Taking turns to spar with her are Yuria Pascual, a 26-year-old biologist, and Ana Gasquez, a French expat who says she was drawn to Cuba by the mystique of its boxing tradition.

Ever ambitious, Moreno has set her sights on “a world and Olympic medal”, adding: “If men can do it, why can’t we?”

Male bastion

It’s an ugly paradox for these women that since 2006 Cuba has been represented in the female programs in all Olympic sports, including weightlifting and wrestling – but not in that last bastion of Cuban machismo, inside the ropes of a boxing ring.

It is generally accepted here that boxing is a man’s sport, far too dangerous for women.

Elsewhere, gender equality in sports has evolved and boxing joined the ranks of women’s Olympic events at the 2012 London Games.

Moreno dismisses the views of Cuban men that boxing is too dangerous for her, insisting body protection is more than adequate.

“All combat sports are dangerous, but we have protection for the chest, the head and the mouth.”

The official reluctance to recognize female boxing “will end up discouraging” young women who want to try the ring, she said.

They have role models aplenty across the globe, including Ireland’s undisputed lightweight world champion Katie Taylor, whose path to professional success began with Olympic gold at London 2012.

Help from the boys

Ironically, women are welcome to train in countless boxing gyms across Cuba, and Gasquez acknowledges the gesture from male counterparts at the sport’s grassroots level.

“Boys help us … they don’t discriminate against us,” she said.

Women seemed primed for a breakthrough in 2016, when Cuban Boxing Federation president Alberto Puig announced the possibility of opening competition to females. But three years on, nothing has changed.

They continue to train, fueled by optimism that the Cuban Sports Institute will eventually give a green light to women’s boxing ahead of the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo.

For these women, it’s impossible not to think of Namibia Flores, held up as an example to women boxers but who reached the age of 40 – the age ceiling for competition – without realizing her dream of winning a gold medal.

“I don’t want the same thing happening us,” said Moreno.

Alcides Sagarra, considered by many to be the father of Cuban boxing, believes it is only a matter of time before women take their place among the sport’s icons.

“Cuban women cannot be denied their rights to participate,” said the 82-year-old Sagarra, who trained more than 80 Cuban Olympic and world champions.

Agence France-Presse

You May Also Like

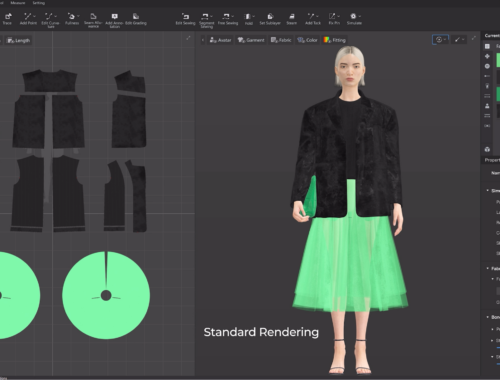

AI in Fashion: Redefining Creativity, Efficiency, and Sustainability in the Industry

February 28, 2025

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for a Smarter Future

February 28, 2025