Focus on long term key to China-US trade

Trade issues pale in importance compared to the need to maintain good economic, political and people-to-people relations between China and the United States.

Most of the economic concerns are short-term and relatively small, but the China-US relationship will shape the state of the world for decades.

I’m an American living in China and married to a Chinese woman, so I have a strong interest in and love for both countries. The deterioration in economic relations over the last 10 years or so frightens me. Let’s look at what is important, and what’s not.

According to a recent study by the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank, imports from China constitute only 1.76 percent of US consumer spending. On the other side, China’s trade with the US amounts to less than 5 percent, or 4.5 trillion yuan (around $660 billion), of its GDP(around 90 trillion yuan in 2018). These numbers are not tiny, but they are also not large enough to affect the lives of most people much.

However, limited groups of workers and companies are directly affected.

A principal goal of both governments is to protect low-skilled industrial workers. The US administration is trying to restore the kinds of factory jobs that once gave working-class people a shot at middle-income lifestyle. And, China is aiming to protect the jobs of factory workers in its export industries.

But, any protection of those low-skilled jobs will have to be short-term and transitional in both countries. US wages have long been too high to allow industries based primarily on low wages to locate there. Only the artificial separation of work forces in India, China, and the former Soviet Union from Western markets allowed those jobs to exist from the 1940s to the 1970s.

In China, incomes and wages have risen sharply, so a business based on low-wage labor will no longer work here either. The only long-term solution for both countries is to upgrade to higher value-added manufacturing and service jobs. The two countries should be focused on how to manage this transition.

Since World War II, the US has had a history of allowing developing nations easy access to its markets, but then restricted this access when a country became more advanced.

From 1945 until about 1970, west European countries, especially Germany, had easy access to US markets and the US did not require access to the European market. European currencies were strongly undervalued. From the US point of view, this was okay when European producers were small and technologically inferior. But, by 1970, the Europeans had caught up, so the Nixon administration responded by removing the tie between the dollar and gold, effectively devaluing the dollar.

Similarly, the Japanese enjoyed easy unreciprocated access to US market from the 1950s through the 1970s. The Japanese yen was strongly undervalued at about 300 yen to the dollar, compared to about 100 today. But, by the 1980s, Japanese companies had become highly competitive with US companies, so the US insisted on a rapid upward revaluation of the yen and imposed quotas on the imports of Japanese cars into the US.

In some ways, the current US position in the trade negotiations is similar to those it had earlier with its Western allies.

Over the last 20 years, the Chinese and American economies have become strongly intertwined. According to the “gravity model” of trade, countries trade primarily with their near neighbors. For example, Canada and Mexico are traditionally major trading partners with the US.

It is unusual for two such distant nations as the US and China to be each other’s leading trading partners. Part of the transition over the coming decade will be a partial separation of the two economies and a diversification of supply chains. America will re-emphasize trade within North America and China will increase trade with the Belt and Road economies.

Americans need to realize that China has to upgrade its productivity and its technology. This is the only way it can escape the middle-income trap over the next 10 years.

This upgrading is driven primarily by Chinese firms competing in China’s highly competitive markets. Senior leaders of tech companies tell me that the Chinese tech market is much more competitive than Silicon Valley is. Many Americans stress the roles of State-owned enterprises and government R&D or investment subsidies, but these factors are small compared to the role of China’s competitive entrepreneurial firms.

American strategic thinkers often write about four “instruments of national power”-diplomatic, military, informational and economic. Some uses of economic influence are positive. For instance, the US Marshall Plan after World War II or China’s Belt and Road Initiative today link people and economies together for mutual benefit.

Of course, other uses of the economic instruments of power are negative, such as sanctions and tariffs. Sometimes sanctions serve a good purpose. For example, the Reagan administration’s sanctions against South Africa in the 1980s helped bring about the end of apartheid. But, those are rare cases.

More often, the negative use of economic power will cause long-lasting animosities but will not have the desired long-term goal. Europe and China will be highly motivated to develop financial systems and technological capabilities that are not subject to US control.

There are definitely some influential people in the current and past US administrations who write a lot about stopping the rise of China as a “peer competitor”. In my view, this is just silly. The world is not the same as it was in 1990. The Chinese economy already exceeds the size of the US economy on a purchasing power parity (local price adjusted) basis and will soon exceed it in terms of measured GDP. The two countries will always be partly rivals in business and international politics, but they don’t have to be hostile rivals.

Hundreds of thousands of influential Chinese know the US firsthand. They have seen both its good sides and its bad sides. But few Americans have any real idea of life in China. My perception from living in Beijing and visiting many other cities in China is that there’s not much difference in the daily life in the two countries, with some advantages in China and others in the US.

Western media coverage almost invariably focuses on negative aspects of life in China. A 2013 study by the Reuters Institute at Oxford University analyzed stories in New York Times, BBC, and Economist magazine. The study concluded that coverage of China is narrowly focused, looks mostly at negative issues such as corruption or pollution, and gives only minimal coverage to important issues such as social change, culture, or science and technology. This just adds to the possibility that animosities could build up between peoples.

On Tuesday, President Trump described the trade dispute as “a little squabble” in the midst of a good relationship. In terms of long-term economics, he is right.

But, Winston Churchill said: “History is just one damn thing after another.” The only really important goal is to be sure that the relationship between China and the US does not become one of those things. From a hard-headed realist point of view, the disputes between the US and China look small and short-term compared to the real interests we share in common.

You May Also Like

シャーシ設計の最適化手法とその応用

March 20, 2025

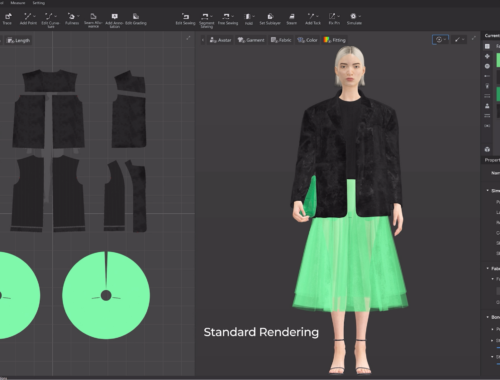

AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion

February 28, 2025