Bundy Faces a Fate Worse Than Prison: Irrelevance

>

Cliven Bundy’s newfound freedom has cost him the most legitimate pulpit he ever possessed. For more than two years, he had been held on charges stemming from a 2014 standoff with federal officials over his refusal to pay grazing fees to the Bureau of Land Management. In that time, he commanded supporters on Facebook, Fox News, and conservative talk radio. Then, earlier this month, Nevada U.S. District Judge Gloria Navarro tossed out the scofflaw rancher’s case, seemingly ending the saga. Speaking with reporters after he walked free, Bundy seemed to yearn for the trial that could have been.

“Judge Navarro, she did the government a very big favor,” Bundy said, adding that “there were a lot of things she covered up and protected from coming to the media and the people. If we go back to court, it’ll all come out.”

Indeed, Bundy wants to go back to court. The Nevada rancher has hired a lawyer and reportedly will file a lawsuit that would ask the judge to determine who, exactly, owns the land Bundy has been grazing his cattle on. Bundy’s argument that the federal government has no authority to hold and manage land rests on dubious, if not altogether false, legal grounds. The Supreme Court has declared over and over and over again to the contrary. But rather than a legitimate legal challenge, this lawsuit seems aimed at a different end: keeping Bundy in the spotlight.

Exhibit A is Bundy’s attorney, Larry Klayman, who has made a name for himself by chasing conspiratorial lawsuits. He has sued both Bill and Hillary Clinton for matters related to sex scandals and the Benghazi attack. In 2014, Klayman sued the Obama administration, alleging that weak Ebola screening at airports was “a reckless plan to open the door not just to Defendant Obama’s infected fellow Africans, but also American Muslim ISIS suicide terrorists.” Many of Klayman’s cases have been dismissed.

With regard to Bundy’s case, Klayman has argued that the federal government can’t charge the family to graze cattle on federal land because the property was ceded to Nevada upon statehood. “That land does not belong to BLM,” Klayman told E&E News last week. “If you look at the Constitution, the government can only own land under certain circumstances.”

Klayman’s reasoning is based on a notion that the federal government held all western land in trust for future states. This view is widely interpreted as false. In a forthcoming law review article, Ian Bartrum, law professor at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, writes that the trust doctrine, as this argument is known, is rooted in an interpretation of the Articles of Confederation, the document signed by the original 13 U.S. states as a stand-in for the Constitution. There is, in fact, nothing in the Constitution itself that requires the feds to turn land over to the states, and Article 4 of the Constitution, which contains the Property Clause, never obligated the federal government to hand land back over to the states, which is just one of the many legal oversights made by the Bundys.

Poke hard enough and the family’s other legal claims crumble as well.The 1877 water rights Bundy crows about appear to be bogus, in part, because his family didn’t buy the ranch until 1948 (his dad first applied for a grazing permit in 1953), and no ancestors filed a Homestead Act claim, the federal government program in the 1800s that ceded federal land to citizens willing to settle it.

“Bundy’s best arguments are (and always have been) political and not legal,” Bartrum writes. (The emphases are his.) “There is almost no chance that the federal courts will reverse more than a century of constitutional doctrine and try to force Congress to relinquish its landholdings in Nevada or anywhere else.”

Outlandish behavior earned Bundy and his children national attention, but their relegation to fringe lawsuits with an equally outlandish lawyer could indicate waning influence for Bundy. The trial in Nevada was a chance for Bundy to be vindicated by a jury, and Gregg Cawley, a political science professor at the University of Wyoming who researches federal land policy, sees this lawsuit as a grasp at influence.

“I think it’s very clear he wanted to use the court case as a platform to raise this whole issue about the legality of the federal estate,” Cawley says.But Navarro tossing the case might ironically sentence Bundy to a fate worse than prison time: irrelevance. He still owes more than $1 million to the government for illegally grazing his cattle (which remain in Gold Butte National Monument, by the way), and his lawyer is trying to gin up a meeting between the rancher and President Donald Trump. In this context, the lawsuit might just be a ploy for press. Unfortunately for Bundy, the West tends to have a short memory when it comes to rangeland outbursts.

“We had the Bucket Brigade up in the Klamath Valley, the Shovel Brigade down in Nevada,” Cawley says. “These are all flare-ups of the so-called Sagebrush Rebellion over time. They get a lot of coverage in their moment, and then they disappear. I’m under the impression that’s what’s going to happen with Cliven.”

You May Also Like

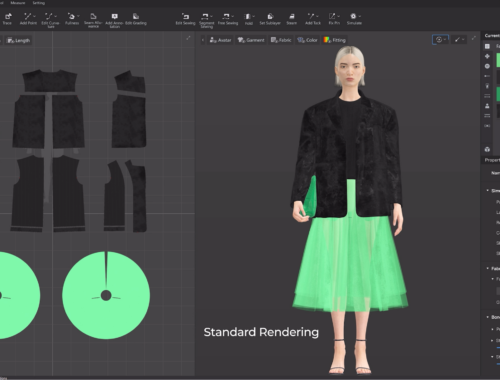

Revolutionizing Fashion: How AI is Redefining Design and Sustainability

March 1, 2025

Dino Game: A Timeless Classic in the World of Online Gaming

March 22, 2025