7 Keys to Setting Your Marathon PR

Whether you’re trying to qualify for Boston or just see improvement, these principles will get you there

Most serious amateur runners want to qualify for the Boston Marathon. The historic race from Hopkinton, Massachusetts, to Boston’s Copley Square is the world’s oldest annual marathon and serves as a mecca for the running community—an experience that many speak of as if it were a religious pilgrimage. Unfortunately, a big part of what makes the Boston Marathon so alluring is also its most significant problem: Qualifying for the race is incredibly hard. The standards, which are adjusted for age and sex, ensure that only the very best toe the start line. Getting there almost always requires breaking through a stubborn personal barrier.

For me, as a 31-year-old male, that barrier is three hours and five minutes. I finished my past three marathons in 3:06:23, 3:07:22, and a devastatingly close 3:05:42. Each of those races, and the training leading up to them, presented a formidable challenge. I have no collegiate, high school, or even middle school running background. In my prime athletic days, I was a 200-pound tight end and outside linebacker; I never ran farther than a 40-yard dash. Like many runners, I picked up the sport later in life and have had to claw to shave every additional second off my finishing times, working my way down from my first marathon, in 2007, of 3:44:25. And yet I was still stuck ever so slightly above my Boston qualifying time.

This past August, I resolved to get unstuck—to break my personal barrier and finally run a marathon under 3:05. The race I selected for my attempt was the Two Cities Marathon in Fresno, California, a small-town event with a good chance of mild weather and, being only a three-hour drive from my apartment in Oakland, minimal logistics. More than a few friends asked me of all the possible marathons, why Fresno? I told them it was a business trip.

To increase the odds that I’d take care of said business, I enlisted the help of Mario Fraioli and Doug Maclean, two marathon coaches with vast experience guiding runners like me to Boston qualifying times. They were both confident that if I adhered to a few critical principles over the course of a three- to four-month training build, I’d hit my mark.

Race morning came with cool temperatures (hooray!) and moderate winds (yuck!). I went out right on 3:05 pace, and though I never felt great, I kept telling myself to trust my training, that it would carry me through. Eight energy gels, two blisters, and 3:03:55 later, it did. Here’s why.

Consistent Volume Is Key

“There is nothing as important as consistency,” says Maclean. “Your overall training volume over the course of weeks, months, and even years is much more important than the volume of any single session.”

For me, this meant gradually increasing my training volume from 40 to 50 miles per week to 50 to 60 miles, as well as doing fewer heroic workouts to minimize the chance of illness and injury.

Don’t Neglect Speedwork

“If you want to run fast on race day, you’ve got to run fast in training,” says Maclean. “Interval training not only builds a lot of fitness in a limited amount of time, but also ensures that your brain, nervous system, and muscles are acclimated to the kind of intensity you’ll bring to race day.”

In past training bouts, I rarely ran intervals longer than one mile. This time around, I did weekly speed workouts, progressing up from quarter-mile to half-mile and eventually mile repeats.

Keep Easy Days Easy So Hard Days Can Be Hard

“When you’re training for performance, every run should have a purpose,” Fraioli says. “Easy runs are a strategic part of training that allow you to recover so you can get more out of your toughest workouts. Avoid the medium-hard ‘gray zone’ that many marathoners fall into.”

I kept all my easy runs—on average, three per week—truly easy. This almost always meant running at a nine-minute-per-mile pace, significantly slower than the 5:50 to 7:30 range my other runs fell into. These super-slow easy runs were the reason I could run fast on my hard days.

You Can’t Fake Fueling

“Just like your car is going to struggle to complete a long road trip if it’s left running on fumes,” says Fraioli, “so will you at the end of a marathon if you’re not keeping your tank topped off during the race. Use your longer training runs to understand how you burn fuel at different paces.”

I experimented with different gels and sports drinks during all training runs longer than 75 minutes and learned that I needed (and trained my stomach to tolerate) between 250 and 350 calories of carbohydrates every hour.

Strength Train

“All too often, you see runners doing the skeleton dance—their form totally falling apart at the end of a marathon,” Fraioli says. “Sometimes that’s due to fueling issues, but other times it’s because their body can’t handle the muscular demands of the race.”

Fraioli suggests spending 30 to 60 minutes per week doing resistance exercise with weights (or your own body weight) to strengthen your musculoskeletal system. I completed a minimalist strength workout two to three times every week. I tried to knock this out in the afternoon following a morning hard run so my easy days would be kept completely easy.

Focus on Performance, Not the Number on a Scale

Lots of runners get fixated on hitting a certain weight, says Maclean, but what really matters is performance. “Being lean is advantageous, but if you’re going to levels of leanness where it’s affecting your health, then it’s also going to have negative impacts on performance and will likely increase your susceptibility to injury.”

There’s also the mental aspect: If cutting weight is making you miserable, then that’s going to make you resent your training. I didn’t weigh myself once during my training build. I simply focused on fueling workouts appropriately and eating high-quality foods throughout the day. Per Maclean’s suggestion, I sought validation (and measured progress) by dropping seconds off my workouts, not by dropping pounds. I definitely got lighter—as evidenced by how my pants fit—but I never made doing so a primary objective. It was merely a byproduct of hard training and good nutrition.

Take Recovery Seriously

“You’re not as good as the workouts you do—you’re only as good as how you recover from them,” says Fraioli. “Take your recovery as seriously as your most challenging sessions. Nail the big basics first: sleep and nutrition, keeping your easy days easy, and being flexible in your approach if you’re feeling overly tired or stressed.”

In the past, I’d skimp on recovery, often so I could get in more training. This time around, I didn’t view recovery as something separate from my training or something that came at the expense of it; rather, I viewed recovery as an integral part of my training. Taken together with the other principles, it paid off.

Brad Stulberg (@Bstulberg) writes Outside’s Science of Performance column and is the author of the new book Peak Performance: Elevate Your Game, Avoid Burnout, and Thrive with the New Science of Success.

You May Also Like

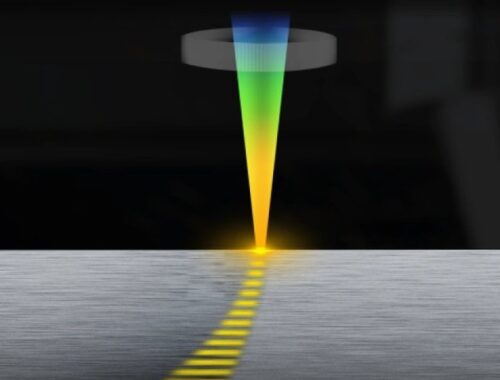

HOW TO IMPROVE PRODUCTION EFFICIENCY OF A LASER PLATE CUTTING MACHINE

November 22, 2024

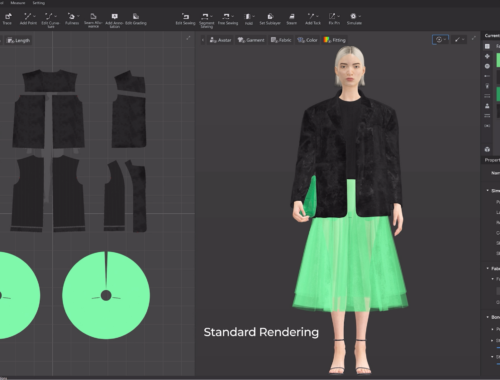

AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion

February 28, 2025